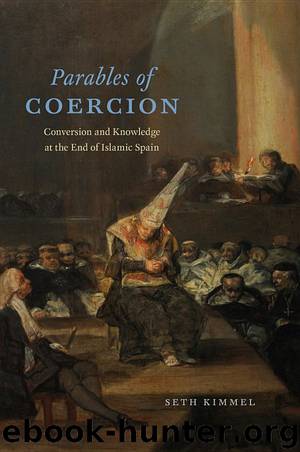

Parables of Coercion: Conversion and Knowledge at the End of Islamic Spain by Seth Kimmel

Author:Seth Kimmel [Kimmel, Seth]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780226278315

Publisher: The University of Chicago Press

Published: 2015-08-20T04:00:00+00:00

RECONSTRUCTING THE WAR’S ORIGINS

Hurtado de Mendoza, Mármol Carvajal, Pérez de Hita, and Juan Rufo all detailed two principal causes for the explosion of hostilities in late 1568. The first and most obvious impetus for war was the pronouncement of the nueva pragmática at the beginning of 1567. The restrictions, which signaled the end of a forty-year royal policy of dispensation, angered the Granadan Morisco community. Though the elderly Morisco Francisco Núñez Muley pleaded his countrymen’s case with the president of the Chancellery of Granada, Pedro de Deza, he was unable to convince either Deza or the Crown to delay once again the implementation of these restrictions. In Hurtado de Mendoza’s and Mármol Carvajal’s views, the second major cause for the Alpujarras uprising was the Moriscos’ belief in a series of false prophecies that foretold the imminent end of Christian rule in Granada. These divinations, which were likely invented by Islamic jurists in the years after the fall of Nasrid Granada and then revised and recorded by learned members of the Morisco community some decades later, predicted that the reversal of the reconquista would begin with a Granadan rebellion. To examine the origins of the Alpujarras uprising was thus to study both the war’s immediate legal context and a deeper history of Morisco piety, class hierarchy, and political antagonism.

As you will recall from chapter 1, Núñez Muley submitted his petition nearly two years before the start of the uprising, but Hurtado de Mendoza’s and Mármol Carvajal’s accounts of his confrontation with Deza in different ways conflated the petition’s failure and the subsequent armed conflict. Imitating Thucydides’s penchant for oratorical set pieces in his History of the Peloponnesian War, both Hurtado de Mendoza and Mármol Carvajal fictionalized Núñez Muley’s petition as a speech.40 In Guerra de Granada, Hurtado de Mendoza presented Núñez Muley’s words in the mouth of the rebel leader, Fernando de Valor el-Zaguer. Though Valor el-Zaguer’s speech was a much-condensed version of Núñez Muley’s text, Hurtado de Mendoza did convey the petition’s fundamental point, which was that a misunderstanding between Old and New Christians threatened to produce a civil war of “Spaniards against Spaniards.”41 By warning against the dangers of Christianity’s expansion into the cultural sphere, Núñez Muley had attempted to avoid such violent confrontation, and he framed his defense of Morisco cultural autonomy as a protection of Christian orthodoxy. By focusing on the martial rhetoric rather than the religious and cultural arguments articulated by Núñez Muley, however, Hurtado de Mendoza’s version of Núñez Muley’s words was nothing less than a call to arms: “Such was the speech that Fernando de Valor el Zaguer gave them,” Hurtado de Mendoza related, that his countrymen “ended up energized, indignant, and generally resolved immediately to rebel.”42 In Hurtado de Mendoza’s view, the Moriscos were neither religious heretics seeking to undermine Christian orthodoxy nor well-intentioned subjects hoping to protect the integrity of the Crown and the unity of peninsular Christianity. They were rebels whose actions were disloyal but whose complaints were comprehensible.

Hurtado de Mendoza’s

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Resisting Happiness by Matthew Kelly(3346)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3039)

Day by Elie Wiesel(2788)

Designing Your Life by Bill Burnett(2751)

The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein(2348)

Human Design by Chetan Parkyn(2078)

The Supreme Gift by Paulo Coelho(1987)

Angels of God: The Bible, the Church and the Heavenly Hosts by Mike Aquilina(1971)

Jesus of Nazareth by Joseph Ratzinger(1816)

Hostage to the Devil by Malachi Martin(1810)

Augustine: Conversions to Confessions by Robin Lane Fox(1779)

7 Secrets of Divine Mercy by Vinny Flynn(1752)

Dark Mysteries of the Vatican by H. Paul Jeffers(1726)

The Vatican Pimpernel by Brian Fleming(1705)

St. Thomas Aquinas by G. K. Chesterton(1639)

Saints & Angels by Doreen Virtue(1609)

The Ratline by Philippe Sands(1583)

My Daily Catholic Bible, NABRE by Thigpen Edited by Dr. Paul(1508)

Called to Life by Jacques Philippe(1484)