Paleopathology in Perspective by Weiss Elizabeth;

Author:Weiss, Elizabeth; [Weiss, Elizabeth]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Incorporated

Published: 2014-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

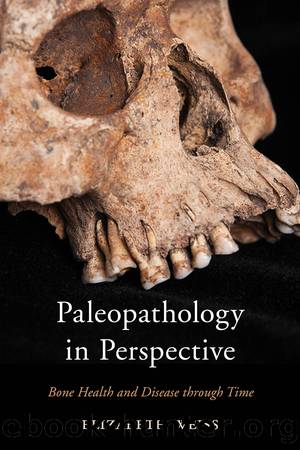

Figure 7.7. Malocclusion. Although usually associated with modernity, even in prehistoric samples malocclusion occurs, and perfect occlusion is rare. Here is an example of a pre-contact California Amerind with an overbite. Photograph by Daniel Salcedo.

Although malocclusion can result from tooth wear and tooth loss, most malocclusion discussions in anthropology have been in regard to malocclusion from a mismatch between tooth and jaw size. Normando et al. (2011) commented that the etiology of malocclusion is unclear, but anthropologists have defined it as a âdisease of civilizationâ and blamed processed foods for the increase in malocclusion. One must first ask, however, whether an increase in malocclusion has occurred through time.

Malocclusion rates in modern populations range from 40% to 80% (Daragiu and Ghergic 2012; Evensen and Ãgaard 2007); before the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it appears that malocclusion was rare. Yet there is a Neanderthal with malocclusion dated to one hundred thousand years ago, and missing molars have been reported in skulls dating over ten thousand years old. Evensen and Ãgaard (2007) found a low rate of severe malocclusion in a sample of medieval skulls from Oslo compared to modern Norwegians. In their research, they found that 65% of modern Norwegians with malocclusions needed treatment, whereas medieval skulls would have required treatment only 36% of the time. Lavelle (1976), looking at a large sample of modern British people, medieval British people, Anglo-Saxons, and modern Africans and Asians, found that the modern British population had the most over-crowding. In Japan, malocclusion rates have been traced from 1000â500 BC (i.e., hunter-gatherer Jomon) to modern Japanese (1964â1966). The Japanese Jomon hunter-gatherers had malocclusion rates of about 20%, whereas agricultural Japanese had rates of malocclusion that were close to 50%; the modern Japanese malocclusion rate is 76% (Larsen 1997). This increase has been tied to a softer diet that prevents strong jaw growth. Other cases of increased malocclusion with a softer diet come from Pima Indians (Corruccini et al. 1983). Larsen (1995) reviewed the literature on malocclusion in relation to the adoption of agriculture and found that dietary changes led to an increase in malocclusion throughout the Americas. In short, those studying rates of malocclusion in the past compared to agricultural or industrial societies have suggested that the ease of processed food consumption reduced jawbone size (by reducing the stresses on the bone and thereby reducing bone remodeling), but tooth size is more firmly controlled by genetics and thus did not change much. Some studies on the Hamann-Todd Collection, the Terry Collection, and the Forensic Anthropology Database have found that mandibles have actually been getting longer from the early twentieth century to the later twentieth century (Martin and Danforth 2009). Martin and Danforth suggested that the change is a result of better nutrition. Not all researchers are convinced by the environmental argument for malocclusion (see McKeever 2012). Normando et al. (2011) found malocclusion in Amazon tribes and linked it to genetics. The two tribes examined included a large diverse village and a village that resulted from a group of individuals who splintered off from the larger population.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4133)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(3764)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3530)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3240)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3200)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3147)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(2963)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(2886)

Hedgerow by John Wright(2783)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(2778)

Origin Story by David Christian(2694)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(2672)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(2668)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(2652)

Water by Ian Miller(2599)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(2590)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2459)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2368)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2339)