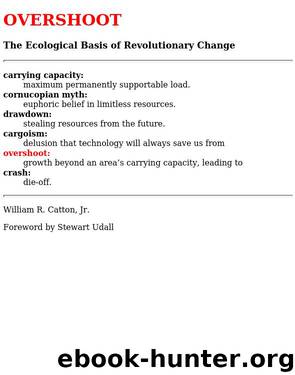

Overshoot, the Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change by William R Catton

Author:William R Catton

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: human ecology, social change

ISBN: 0-252-00988-6

Environmental Brakes on Exuberance

Modern nations had staked their future on perpetual harvesting of supplies of non-renewable resources. Men now built with steel, concrete, or aluminum, rather than with wood. We had evolved into societies so large and complex that they required quantities of energy too vast to be supplied by contemporary crops of organic fuel. We allowed ourselves to become so numerous that we could not really grow the food we needed without enormous “energy subsidies,” augmenting sunlight and muscle power in agriculture with industrially produced chemical fertilizers and fuel-burning machinery for planting, cultivating, harvesting, shipping and processing.11 Americans thus were farming not only the great plains of Iowa and Nebraska but also the gas wells of Texas and Alaska and the oil wells of the continental shelf offshore. Even agriculture, the ultimate achievement in man’s development of the takeover method of carrying capacity expansion, had become converted to drawdown methods. The most “prosperous” nations were living on phantom carrying capacity but had not learned the concept. By using still more enormous quantities of energy for new occupations unrelated to agriculture, we put off recognizing that our population had outgrown its maintainable niches. Had people understood the ecological implications of the Industrial Revolution, it might have been seen not so much as a great step forward for mankind but, as we shall make clear in Chapter 10, as a tragic transition to human dependence on temporarily available resources.

To provide charcoal for iron smelting, the British in the eighteenth century had harvested their timber faster than it grew. Depletion of British forests led to increased coal mining.12 The need for pumping devices to remove water seeping into the mines provided the impetus for development of steam engines. Those engines could convert the chemical energy in a fuel such as coal into mechanical energy that could do useful work. In addition to working the pumps at the mines, other applications for steam engines were soon found, and they made great industrial expansion possible. Reliance on current photosynthesis (annual timber growth) was replaced by dependence on accumulated past photosynthesis (coal deposits). There was a rapid proliferation of coal-consuming machinery. As a result, Britain evolved an economy that traded British factory output for food and other agricultural products grown overseas. Those doublings of British population sine Malthus, and the exporting of British people to other lands around the world, were thus made possible by exchanging a way of life based on visible acreage for a way of life based on two levels of ghost acreage. By heavy use of fossil acreage, British industry produced the goods that gave Britain access to trade acreage.

So British exuberance since Malthus was no refutation of the Malthusian principle. By the drawdown method Britons merely postponed the day of reckoning. They lived beyond their energy income, harvesting timber on a faster-than-sustained-yield basis. Then they bought further time by exploiting ghost acreage—both overseas and underground. Despite such measures, only two hundred years after James Watt’s invention, the time Britain had thus bought seemed to be running out.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anatomy | Animals |

| Bacteriology | Biochemistry |

| Bioelectricity | Bioinformatics |

| Biology | Biophysics |

| Biotechnology | Botany |

| Ecology | Genetics |

| Paleontology | Plants |

| Taxonomic Classification | Zoology |

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14390)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12659)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(7347)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6944)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6941)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(6726)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5558)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5372)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5098)

The Longevity Diet by Valter Longo(5065)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4970)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4589)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4474)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(4447)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4383)

Yoga Anatomy by Kaminoff Leslie(4364)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4323)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4273)

Embedded Programming with Modern C++ Cookbook by Igor Viarheichyk(4182)