My Place in the Sun by George Stevens Jr

Author:George Stevens Jr.

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780813195254

Publisher: The University Press of Kentucky

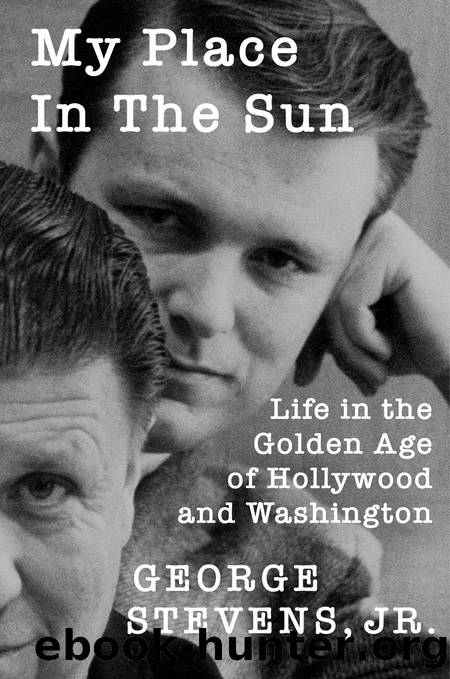

Federico Fellini, left, Anthony Quinn and George Stevens, Jr., in AFIâs Great Hall, January 1970.

This was a crucial moment for our new academy. The conservatory was there to advance the principle that creativity goes hand in hand with craftsmanship and discipline, and that night the man who was arguably the worldâs most imaginative director spoke up for preparation, calculation and structure.

42

Nixon in Charge

The tumultuous year of 1968 ended with the election of Richard Nixon. He defeated Hubert Humphrey, whose alignment with Johnson on the Vietnam War cost him support, while touting a secret plan to end the conflict. We could only hope that Nixon did indeed plan on ending it.

The American Film Institute was off to a strong start and well into its second year when Nixon took office. The arts were bipartisan and we looked forward to a smooth transition at the National Endowment for the Arts. It was widely expected that NEA chairman Roger Stevens, the prime architect of the organization who was just two years into his term, would be asked to continue, but Nixon appointed Nancy Hanks, who had worked at the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. She was politically adept and less deferential to members of the arts council than her predecessor, and decided to change course with AFI.

Hanks set up a Public Media Program within NEA that would support programs in film similar to AFI. It would have its own director, as well as a Public Media Panel, a small body of advisers akin to AFIâs board of trustees that would approve projects and funding. NEA would retain for its Public Media Program the lionâs share of the funding that Roger Stevens assured AFI it could expect, and when AFI applied for funding, our proposals and performance would be judged by the NEA Public Media staff and panelists, our new competitors.

AFI had initiated major programs in preservation, cataloging, and support for independent filmmakers, as well as establishing the Center for Advanced Film Studies. We made those commitments based on the assurance of stable funding from the National Endowment. NEA had created AFI on the premise that a nongovernmental organization would have a capacity for creativity and innovation that a purely governmental program would not. We were suddenly swimming against the tide.

The chairs of the arts-related committees in Congress, Senator Claiborne Pell of Rhode Island and Representative John Brademas of Indiana, were believers in AFI, as were many others on both sides of the aisle. As Hanksâ intentions became clear they weighed in, urging her to support AFI in the fashion originally contemplated, but Hanks stood her ground. At one stage Brademas and Pell introduced legislation that would separate AFI from the endowment and fund it directly by Congressâsimilar to the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian. Brademas, a Rhodes Scholar who would one day become president of New York University, shepherded the legislation in the face of NEA resistance. The bill fell short of the votes necessary.

âFilm as an art form had a golden opportunity to move on to the national level,â said Brademasâ legislative aide Jack Duncan.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Direction & Production | Reference |

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5181)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(4654)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(4405)

The Perils of Being Moderately Famous by Soha Ali Khan(4221)

The 101 Dalmatians by Dodie Smith(3511)

Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee(3470)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(3439)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3309)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3272)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3074)

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald by J. K. Rowling(3059)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(3005)

The Mental Game of Writing: How to Overcome Obstacles, Stay Creative and Productive, and Free Your Mind for Success by James Scott Bell(2909)

4 - Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by J.K. Rowling(2703)

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting by Syd Field(2644)

The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Reader by H.P. Lovecraft(2564)

Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema by Anne Helen Petersen(2526)

Wildflower by Drew Barrymore(2489)

Robin by Dave Itzkoff(2441)