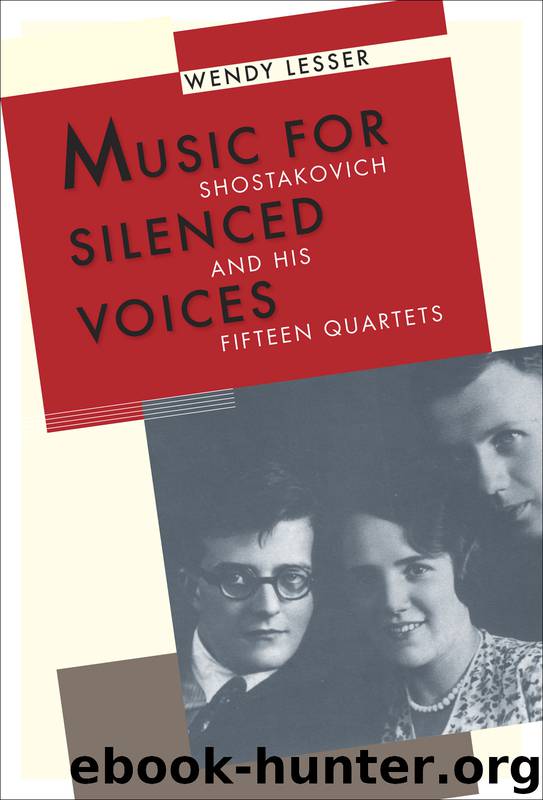

Music for Silenced Voices by Wendy Lesser

Author:Wendy Lesser

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2011-03-16T16:00:00+00:00

They were listening instead, in the period immediately preceding this quartet, to his latest symphony and his revived opera. And if op. 114 (the number he assigned to the updated Lady Macbeth under its new name, Katerina Izmailova) was eventually an unqualified success, op. 113 was another matter entirely. Shostakovich’s Thirteenth Symphony, based on five poems by the rebellious and self-proclaimedly “precocious” poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, premiered on December 18, 1962, to a resounding silence in the press. (There was one small notice about it on the morning after the first performance; that was all.) Up until the very day of the Moscow premiere, the composer and his performers didn’t even know whether the symphony would be allowed to go on: it didn’t receive Khrushchev’s approval until the afternoon of the 18th itself. A second Moscow performance took place two days later, and then a few more scattered performances occurred in February and March of 1963. After that, the Thirteenth Symphony was quietly dropped from the repertory—not because of any official ban, but because everyone understood that it was too hot to touch, politically.

What made it politically dangerous was the language of the poems, which is what had drawn Shostakovich to the project in the first place. The first and longest movement is an Adagio setting for “Babi Yar,” Yevtushenko’s now-famous poem against Russian anti-Semitism. “They smell of vodka and onions. … They guffaw ‘Kill the Yids! Save Russia!’” are some of its lines about the perpetrators of pogroms, and though this was the movement that caused all the trouble—including officially imposed rewrites of the text—other sections seem equally problematic. “Humor,” the Allegretto second movement, has the title character, humor itself, captured as a “political prisoner.” “Fears” (a Largo movement) talks about the bad old days of “an anonymous denunciation … a knock at the door.” And the final movement, a strangely despairing Allegretto setting for the poem “A Career,” muses about an unknown, unsung scientist in Galileo’s time who “was no more stupid than Galileo,” who also “knew that the earth revolved, but he had a family.” Cheery stuff for a man with Shostakovich’s history of real fears and forced compromises.

We know from his letters, and from the fact that he undertook this obviously dangerous work, that the poems affected the composer very personally. But sincerity and even bravery do not guarantee aesthetic success. The Thirteenth Symphony, to my ear, is filled with the kind of bombastic urgency that makes you want to resist its patently commendable sentiments. The composition features a rather tuneless bass solo line against a background of heavy male chorus and portentous orchestral accompaniment, replete with clashing cymbals, whirring tambourines, and ringing church bells. It is more like a hymn than a symphony, and at times even more like a melodramatic movie soundtrack. Still, its aesthetics are not what caused the problem with its reception. Shostakovich had always been allowed, even encouraged, to produce bombastic symphonies, as long as the ostensible political content was the approved one.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(12432)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(10519)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(6866)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(5527)

Assassin’s Fate by Robin Hobb(5236)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(4880)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4001)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(3454)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(2930)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(2901)

Beneath These Shadows by Meghan March(2718)

The Help by Kathryn Stockett(2703)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(2673)

How Music Works by David Byrne(2524)

Jam by Jam (epub)(2487)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(2416)

Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story by David Buckley(2367)

Petty: The Biography by Warren Zanes(2237)

Darker Than the Deepest Sea by Trevor Dann(2206)