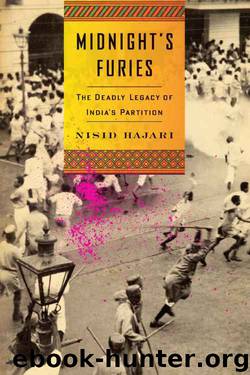

Midnight's Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India's Partition by Nisid Hajari

Author:Nisid Hajari [Hajari, Nisid]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Asia, India & South Asia, Social Science, Violence in Society, History, India, Nonfiction, Retail

ISBN: 9780547669212

Google: bO5zCQAAQBAJ

Amazon: 0547669216

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Published: 2015-05-14T18:30:00+00:00

As a discouraged Ismay flew back to Delhi on 14 September, Nehru was racing the other way, to attend an emergency summit with Liaquat in the Punjab. Jinnah was not the only one talking about a war.

Most accounts of the Partition riots tend to focus on the eruption of violence in mid-August, leaving the impression that the chaos steadily tailed off thereafter. In reality, the massacres grew wider and more intense for weeks. By mid-September, they were approaching their peak. The exodus from both halves of the broken province had assumed biblical proportions. An estimated 1.75 million Muslims had crossed into Pakistan from East Punjab, while a roughly equivalent number of Hindus and Sikhs had emigrated to India.64 Millions more were on the move. Organized refugee convoys—called kafilas—now stretched for 50 miles or more. The tramping of hundreds of thousands of cows, buffalo, and blistered human feet churned up the Punjab’s dirt roads. When these great masses of humanity paused for the night, Life magazine photographer Margaret Bourke-White wrote, the flicker of thousands of campfires “rose into the dust-filled air until it seemed as if a pillar of fire hung over them.”65

One kafila, filled with more than a quarter-million Muslim refugees from East Punjab, had recently begun the long, dangerous march to Lahore. The most direct route would bring them through the Sikh bastion of Amritsar. The city had been emptied of its Muslim population and was now filled with tens of thousands of vengeful Hindu and Sikh refugees from West Punjab. They refused to let the column pass. Crowds chanted “No Muslims out!” and swore that not a single Muslim would cross the border alive.66

Master Tara Singh could not—or would not—rein in his followers. Any remorse he might have felt at the start of the massacres had dissipated as refugees recounted the horrors they had suffered on Pakistan’s side of the border. Meeting with “Timmy” Thimayya, who had been promoted to major-general and was now in charge of Indian troops in East Punjab, Singh said he saw only one way to resolve the worsening conflict: war between India and Pakistan.67

The army did not relish the challenge of reining in the Sikhs. The jathas had grown bigger, bolder, and more organized. They vastly outnumbered the kafila escorts: already, in one assault, a ten-thousand-strong jatha had attacked a detachment of sixty soldiers, wounding their Sikh officer four times.68 Commanders feared their Sikh soldiers would begin to desert if they had to keep fighting their brethren.

Across the table from Liaquat in Lahore, Nehru was forced to admit his government’s impotence. He could not open Amritsar’s gates. The best alternative Thimayya could propose was to bulldoze a new road around the city for Muslim convoys to use.69 The project would take several days. In the meantime, the refugees—who suffered repeated attacks on their journey, and were refused food and water in the villages they passed—would have to wait.

Tara Singh’s idea of carving out a powerful Sikhistan in the Punjab sounded less crazy now. In the Sikh states, ongoing pogroms were denuding villages of Muslims.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Central Asia | Southeast Asia |

| China | Hong Kong |

| India | Japan |

| Korea | Pakistan |

| Philippines | Russia |

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3535)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(3530)

World without end by Ken Follett(3016)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(2933)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2617)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(2567)

City of Djinns: a year in Delhi by William Dalrymple(2141)

Inglorious Empire by Shashi Tharoor(2108)

In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl's Journey to Freedom by Yeonmi Park(2064)

Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2064)

Tokyo by Rob Goss(2025)

India's Ancient Past by R.S. Sharma(1994)

India's biggest cover-up by Dhar Anuj(1992)

The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia by Peter Hopkirk(1966)

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(1953)

Goodbye Madame Butterfly(1942)

The Queen of Nothing by Holly Black(1772)

Living Silence in Burma by Christina Fink(1738)

Batik by Rudolf Smend(1726)