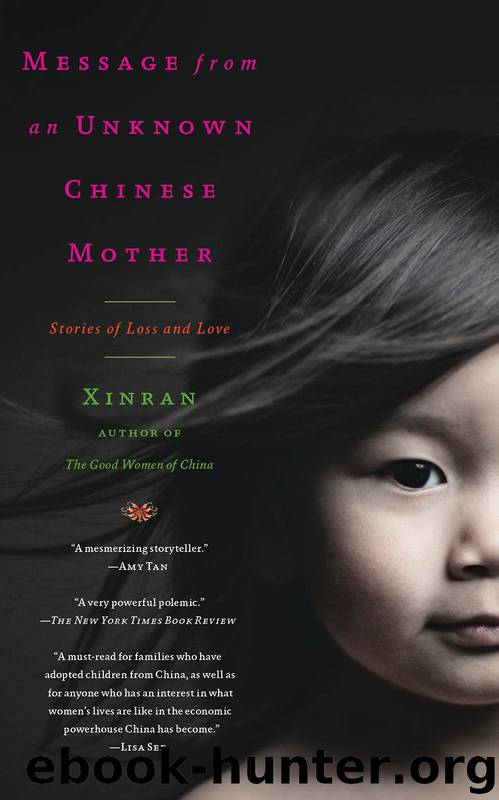

Message from an Unknown Chinese Mother: Stories of Loss and Love by Xinran

Author:Xinran

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Scribner

Published: 2011-03-08T00:00:00+00:00

7

THE MOTHER WHO STILL WAITS IN THE USA

“I can’t write this story myself and it’s been weighing on me for all these years.”

I have met very few Chinese mothers who know anything about how daughters are brought up in Western families. Most of these mothers live a lonely existence, unable to share their burden with anyone. And any hope on the part of adopting families that their Chinese children may one day have the opportunity to thank their birth mothers for keeping them alive can only be remote. Finding the child’s birth mother is like looking for a needle in the proverbial haystack, given how far the West is from the sources of information, and how scant those sources are in China. Before the 1990s most ordinary Chinese in the countryside had no right to a birth certificate or similar personal legal record. In addition, the secrecy with which the Chinese government guards adoption information is compounded by the different ways things are done locally and by the sense of shame that has traditionally surrounded adoption. In mainstream Chinese culture, when people abandon or give up their children for adoption, or get divorced, outsiders do not get involved. These are considered as much private matters between husband and wife as their sex lives. Many families do not even tell children they have been adopted. A childless family is a tragedy; a couple without children have failed.

Babies have been abandoned in China since time immemorial. Ordinary folk did it because they believed that they owed it to the ancestors to give them a son and heir as the firstborn. The gentry and imperial families did it, frequently, in order to protect wealth and interests. At no level of society did anyone want to admit that the flame at the ancestral shrine that could be kept alive only by the eldest son might go out. This extended to the very top of society: every emperor had to be “the real thing,” his powers and privileges rightfully inherited.

Divorce as we understand it today in China is a product of modern Chinese society. Up until the overthrow of the feudal imperial system in 1911, a man could get rid of his wife, but a woman had absolutely no rights to end her marriage. Then with the violent upheavals and political turmoil of the twentieth century, divorce (and remarriage) came to be regarded as a way up the political ladder and to a better life. No one would frankly admit to anyone else that the reason for their divorce was to escape from a marriage so loveless it was unnatural. It was not until the 1980s that Chinese people were able to decide freely about marriage, to make up their minds and look for the kind of family that they really wanted. From that point on, divorce finally became a topic that people talked about openly.

Adoption, in old China, meant taking on the child of a relative. It applied mainly to boys, who joined the adopting family and then shared in the distribution of its wealth.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Civilization & Culture | Expeditions & Discoveries |

| Jewish | Maritime History & Piracy |

| Religious | Slavery & Emancipation |

| Women in History |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32547)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31945)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31931)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19053)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14368)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13316)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12018)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5366)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5215)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5092)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4908)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4769)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4583)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4526)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4465)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4203)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4101)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4089)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3957)