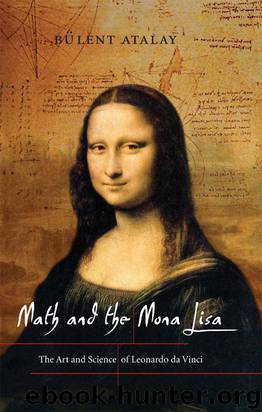

Math and the Mona Lisa by Bulent Atalay

Author:Bulent Atalay [Atalay, Bulent]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 978-1-58834-353-6

Publisher: Smithsonian

Published: 2011-09-20T04:00:00+00:00

The Eye of the Beheld

If I could write the beauty of your eyes

And in fresh numbers, number all your graces,

The age to come would say, “This poet lies;”

His heavenly touches ne’er touch’d earthly faces.10

—William Shakespeare

“Is it the eyes?” wrote Guy Gugliotta, “The light? The sort of smile? What is it that makes the Mona Lisa—one of history’s most memorable portraits—so compelling, even in its creation, that the young Raphael sat at Leonardo’s knee just to watch him paint it?”11 Christopher Tyler, a neuroscientist in San Francisco, and independently, Michael Nicholls and fellow psychologists in Melbourne, compiled complementary evidence of particular symmetries and asymmetries, a lateral bias, in portraits spanning the past five hundred years.

In 1998 Christopher Tyler began to explore the possibility that the asymmetric functions of the two hemispheres of the brain may have somehow manifested themselves differently in artists’ works. It was an unusual approach, although decidedly simple in conception, in which he constructed a vertical line bisecting the frames of each of the portraits. Tyler accepted only seated or standing, but not reclining figures; in all, 282 artists were represented in his study. After he discovered that a preponderance of the center lines passed through one of the eyes of the subject, a “compositionally dominant eye,” he expanded his study to a much larger universe of Western portraiture spanning 2,000 years and ever-changing styles and schools.

For his statistical analysis Tyler tested four hypotheses: the major axis hypothesis, the golden section (divine proportion) hypothesis, the head-centered hypothesis, and the one-eye centered hypothesis. At first glance most observers would agree that the eyes in portraits are generally located near the center of the canvas, but Tyler’s study revealed a subtler element. One eye, either the leading or the trailing eye, was found to lie in a gaussian distribution (bell curve) about the center line with a narrow standard deviation of ±5 percent of the frame width. One-third of the portraits displayed one-eye coincident with the center line and fully two-thirds of the portraits displayed one-eye within 5 percent of the center line. Vertically, Tyler found, the eye height distribution peaked not around the horizontal center line, but rather around the golden ratio of 61.8 percent of the height of the canvas, with only a negligible number of eyes found below the vertical center.12

Tyler published a matrix of nine masterworks of Western civilization, portraits spanning the past five centuries (Plate 12, top). These were chosen to illustrate the variety of compositional asymmetries, yet all have an eye right on the center line. Even Picasso, the ultimate creator-rebel of twentieth-century art in his Portrait of Dora Maar (1937), succumbed to this unwitting, unwritten norm for artists to put an eye at or near the vertical center line (third row, third column). Until the end of the twentieth century, common American currency—from George Washington on the one-dollar bill to Benjamin Franklin on the hundred-dollar bill—had one eye of the subject coincident with the centerline. But then in the last years of the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18606)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5460)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3659)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3526)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3513)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3431)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3343)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3290)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3159)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2904)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2902)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2871)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2707)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2703)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2648)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2622)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2570)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2562)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2494)