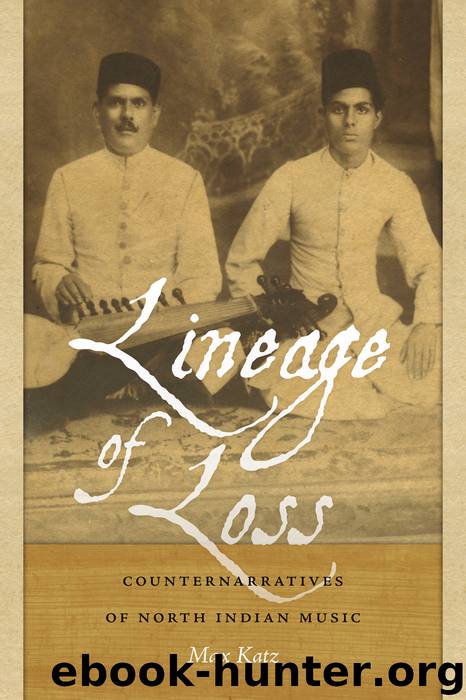

Lineage of Loss by Katz Max;

Author:Katz, Max;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Wesleyan University Press

Published: 2017-03-18T04:00:00+00:00

The Shift

This chapter brings together two dimensions of Hindustani music history that have proven problematic in the literature: institutions and religion. Citing the inability of schools and colleges to produce professional performing artists, scholars have generally dismissed the role played by educational institutions within Hindustani music history. If institutions have been disregarded, the significance of religion has been rigorously denied. As shown in Chapter 3, a small number of high-profile Muslim hereditary professionals flourish in the upper echelons of Hindustani music culture today, yet in general, Muslim musicians have endured a drastic decline in patronage over the past century, pushing many hereditary musical families into the economic and cultural margins. Indeed, no one denies that there has been a marked shift in the population of performing artists in Hindustani music from a Muslim majority to a Hindu majority over the past one hundred years (see Manuel 2007 [1996]: 123; Peterson and Soneji 2008: 7–8; Powers 1980: 27; Qureshi 1991: 162; Slawek 2007: 507).

How do scholars explain such a shift from Muslim to Hindu predominance while minimizing the significance of religious identity? The most convincing arguments, advanced independently by ethnomusicologists Regula Qureshi and Peter Manuel, have leveraged Marx’s theory of mode of production to explain the changing demographics of Hindustani music (Manuel 1986, 1987, 1989a, 1989b, 1991, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2007 [1996], 2008; Qureshi 2000, 2002, 2006).2 Briefly summarized, Qureshi argues that prior to the mid-twentieth century, Hindustani musicians were essentially feudal servants beholden to powerful landed patrons. The patron class appropriated the cultural capital produced from musical performance through their ownership of the means of production: the venue in which the performances took place (2002). From the sixteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries, the great majority of such patrons were Muslim, and thus, Qureshi contends, “their hereditary servants were naturally Muslim” (1991: 161). With independence in 1947, however, the feudal system began to crumble, replaced by capitalism; concomitantly, the old feudal patrons were replaced by the new bourgeoisie. For a variety of reasons, the new patron class was largely Hindu, and thus impelled the rise of a parallel constituency of middle-class Hindu performing artists. Manuel offers a similar analysis, while emphasizing the musical over the social consequences of the shift from feudalism to capitalism. Focusing on the music’s ability to weather broad social changes resulting from the shifting mode of production in India, Manuel notes that “Hindustani music successfully underwent the transition from Muslim feudal patronage to predominately Hindu bourgeois patronage” (2007 [1996]: 125). Like Qureshi, Manuel suggests that this transition produced as a secondary effect the shift from Muslim to Hindu majorities among performers, an unintended consequence of patronage by the new bourgeoisie, which, Manuel notes, “happened to be predominately Hindu” (2008: 396).

Beyond the realm of music, strife between Hindus and Muslims has been a central point of political friction for over one hundred years, yet there remains in the scholarship a reluctance to identify the politics of communalism in the heart of the Hindustani music tradition. Manuel encapsulates the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13650)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11807)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7552)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6194)

Assassin’s Fate by Robin Hobb(6194)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(5782)

Altered Sensations by David Pantalony(5091)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4994)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4186)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(3601)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(3538)

Beneath These Shadows by Meghan March(3298)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3295)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3256)

The Help by Kathryn Stockett(3139)

Jam by Jam (epub)(3071)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3055)

Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing: 20th International Conference, CICLing 2019 La Rochelle, France, April 7â13, 2019 Revised Selected Papers, Part I by Alexander Gelbukh(2978)

Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story by David Buckley(2855)