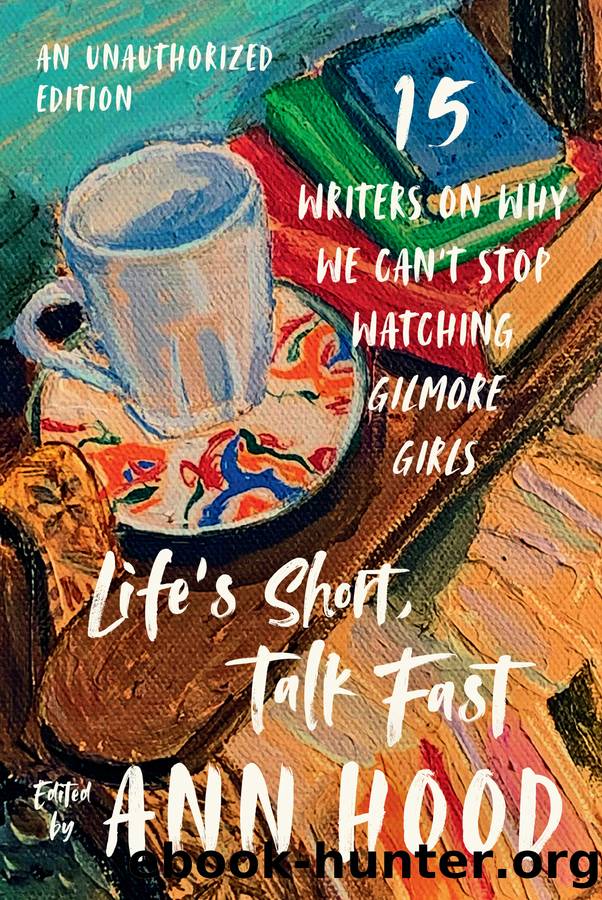

Life's Short, Talk Fast by Ann Hood

Author:Ann Hood

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Hiding in the Floorboards

Sanjena Sathian

Thereâs an iconic moment early in the first season of Gilmore Girls when Rory Gilmore swings by her best friend Lane Kimâs house to borrow a CD. Lane, a spunky Korean American teen played by Keiko Agena, obliges by lifting up loose floorboards in her room to reveal a massive collection of the secular rock-and-roll albums her religious mother wonât allow her to consume.

I was not, myself, actually allowed to consume Gilmore Girls either, which has a mildly scandalous premise: it follows Rory and her thirtysomething single mom, Lorelai, who got pregnant as a teenager. Parenthood out of wedlock was not condoned in my Indian immigrant householdâor in Laneâs. (As Lane tells Lorelai, Mrs. Kim âdoesnât trust unmarried women.â) Nevertheless, I watched Gilmore Girls surreptitiously, and instinctually loved Laneâs rebellious hijinks. She contrives elaborate codes and alibis to finagle a single phone call with a boy. She plans a KGB-worthy covert drop to have Rory deliver the new Belle and Sebastian single when she gets grounded for dating. She tries to âcome outâ to her mother as a rebel a few timesâonce memorably dyeing her hair purple and then redyeing it black in terror; another time calling Mrs. Kim while drunk and declaring her intoxication.

When I was in graduate school, a white guy once read my fiction and noted that my charactersâsecond-generation South Asian teens growing up in a socially conservative immigrant bubbleâengaged in âcontained debauchery,â as though they should have been a little harder-core. Laneâs debauchery might have seemed contained to an outsider, but I know it was plenty serious for her.

In Laneâs scheming, I recognize an exaggerated version of the code-switching that some children of immigrants cultivate as a survival strategy, and in Mrs. Kimâs unbending responses, I see a familiar portrait of a mother intent on protecting her child from the unholy American trifecta of drinking, drugs, and dating. Like Lane, I loved art, often art the adults in my community disapproved of; like Lane, I sequestered my tastes beneath the proverbial floorboards.

Like Mrs. Kim, who eventually (and heartbreakingly) discovers Laneâs secret stash and unravels years of liesâand, hurt and afraid, fears she has lost her daughterâmy parents got wise to my various misbehaviors and shoddy cover-ups. And finally, like the Kims, who find a tenuous peace as Lane enters her twenties, my family and I started to learn how our occasionally diverging values can coexist now that Iâm an adult.

And yet I had none of this language when I was watching Gilmore Girls when it first aired in the early 2000s. As a teenager, I wasnât seeing myself in Lane. I didnât even think of myself as âAsian American,â except when I had to check a box on a standardized form. Then, I reentered the Gilmore Girlsâ utopian setting of Stars Hollow, Connecticut, in the spring of 2021, coming off a year of anti-Asian sentiment, including the spa shooting that killed eight people, most of them Asian women. Turning to the show

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Direction & Production | Genres |

| Guides & Reviews | History & Criticism |

| Reference | Screenwriting |

| Shows |

Robin by Dave Itzkoff(2431)

Head of Drama by Sydney Newman(2282)

I'm Judging You by Luvvie Ajayi(2194)

The Paranormal 13 (13 free books featuring witches, vampires, werewolves, mermaids, psychics, Loki, time travel and more!) by unknow(2083)

Ten by Gretchen McNeil(1877)

Single State of Mind by Andi Dorfman(1802)

#MurderTrending by Gretchen McNeil(1654)

Key to the Sacred Pattern: The Untold Story of Rennes-le-Chateau by Henry Lincoln(1621)

Merv by Merv Griffin(1609)

Most Talkative by Andy Cohen(1585)

Notes from the Upside Down by Guy Adams(1465)

This Is Just My Face by Gabourey Sidibe(1457)

The Hunger Games: Official Illustrated Movie Companion by Egan Kate(1424)

Springfield Confidential by Mike Reiss(1408)

Binging with Babish by Andrew Rea(1406)

Jamie Oliver by Stafford Hildred(1382)

The TV Writer's Workbook: A Creative Approach To Television Scripts by Ellen Sandler(1341)

Clarkson--Look Who's Back by Gwen Russell(1334)

Blue Planet II by James Honeyborne & Mark Brownlow(1273)