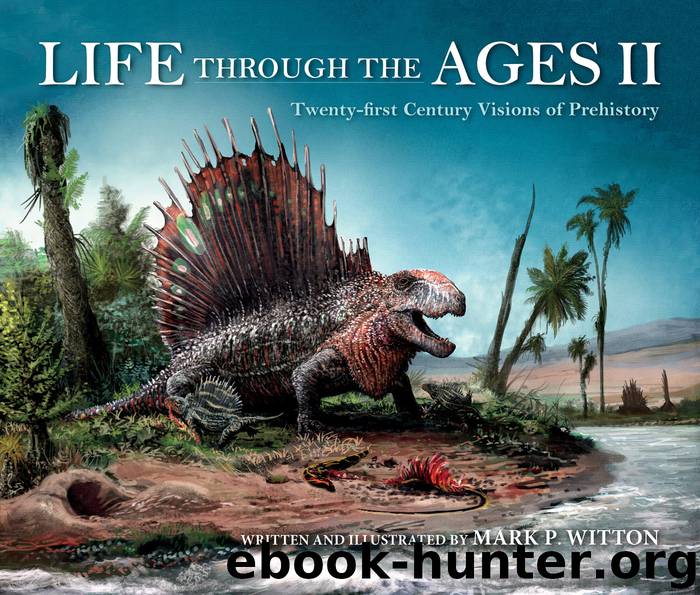

Life Through the Ages II by Mark P. Witton;

Author:Mark P. Witton;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Indiana University Press

Published: 2020-03-14T16:00:00+00:00

Cretoxyrhina and Pteranodon (Cretaceous)

WE TEND TO PORTRAY THE MESOZOIC ERA AS THE TIME OF GREAT sea reptiles—ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, mosasaurs, and so on. While there is little doubt that these animals were important to Mesozoic marine ecosystems, we should not overlook the significance of a more familiar, and yet much more ancient, group of predators that flourished alongside them: the sharks.

Sharks are one of the greatest successes of vertebrate evolution. Their fossil teeth are found in abundance all over the world through the last four hundred million years of the geological record. Fossils of their cartilage skeletons are much rarer, however, and only a few sites of exceptional preservation provide more complete insights into ancient shark anatomy. The chalk sediments deposited by the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow marine sea that bisected North America in the latter half of the Cretaceous Period, are one rock type that yields them. The shark fossils here are excellent and abundant, and they leave no doubt that sharks were an important component of an ecosystem also occupied by plesiosaurs, mosasaurs, and predatory bony fish.

Shark fossils of particular interest from the Western Interior Seaway are those evidencing their biting of other animals. Paleontologists go to great length to reconstruct the diets of fossil animals, and this is aided enormously by bite marks or imbedded teeth in the bones of prey species. Western Interior Seaway shark teeth are frequently preserved in close association with the ancient carcasses of virtually all large vertebrates from this environment, and their bite marks, tooth gouges, and embedded teeth are frequently found on fossil bones. It seems that few animals in this inland sea escaped the jaws of sharks, and we know that they even turned cannibalistic on occasion: sharks eating other sharks. The 2–3-m-long shark Squalicorax falcatus has left particularly pervasive evidence of its foraging habits: its teeth and feeding traces are associated with so many carcasses that it was surely something of a scavenger, eating anything it could find regardless of animal type or size. A larger shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli (shown here), roamed the same waters. At 6–7 m long, it was a top carnivore of the Western Interior Seaway, and fossil evidence directly shows that it dined on even relatively large marine reptiles.

Among the rarest quarry of Cretoxyrhina was Pteranodon, a flying reptile famous for its large, backward-pointing cranial crest; toothless jaws; and wingspan of up to 7 m. In fact, most Pteranodon individuals were much smaller than this, with wingspans of 3–4 m, and they had much smaller cranial crests. It is thought that these smaller morphs were females, and the males were larger and full-crested. The bones of Pteranodon were, like most of its kind, occupied by bony air sacs, so that the bone walls were just a millimeter or so thick. This made for a lightweight and flight-adapted skeleton, but it rendered pterosaur bones highly vulnerable to damage once their owners died. Evidence of carnivorous acts on pterosaur bodies is therefore rare, but we know that pterosaurs were eaten by fish, dinosaurs, ancient relatives of crocodylians, as well as sharks.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Paleobiology | Paleozoology |

| Vertebrate |

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13050)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12029)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6335)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(6234)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(5784)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(5640)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4534)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(4504)

The Longevity Diet by Valter Longo(4445)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3905)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(3826)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3797)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(3771)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(3754)

Yoga Anatomy by Kaminoff Leslie(3700)

Barron's AP Biology by Goldberg M.S. Deborah T(3631)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(3579)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3515)

Yoga Anatomy by Leslie Kaminoff & Amy Matthews(3394)