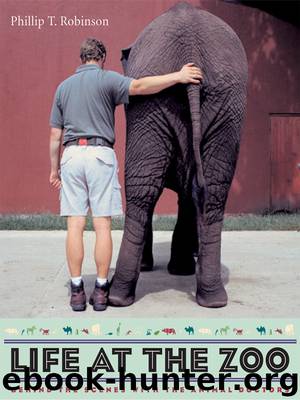

Life at the Zoo by Phillip T. Robinson

Author:Phillip T. Robinson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Nature/Animals

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2011-12-22T16:00:00+00:00

Tapeworm life cycle in a zoo bear

Wild animals frequently recover from a wide variety of infections and injuries during their lifetimes, although any serious injury can make an individual much more vulnerable to death from predation. Some insightful studies have been done by the examination the skeletons of wildlife that have been collected for museums in various parts of the world, revealing a wide range of dental and skeletal diseases that animals must have experienced for extended periods of time. Primates in one study had arthritis and healed fractures of arms, legs, fingers, and toes. Of all the primates examined, the group with an astonishingly high rate of healed fractures of arms was the gibbons, which are highly arboreal in habit, swinging dramatically between tree branches. Fortunately for early zoo veterinarians, many animals healed from their injuries despite their lack of medical treatment. Dental disease, such as tooth abscesses and fractures, has also been found to occur in many primate species, but more particularly in wild apes, especially older individuals. Not surprisingly, comparisons with zoo apes revealed that dental decay is much more common in captive animals than in their wild counterparts, suggesting shortcomings in diet, behavior, or environment.

As animals age in the wild, the loss of dental competency limits their lifespan. Wild Weddell seals, for example, live under large ice packs in the Antarctic and survive far from open water by maintaining open breathing holes through the ice, gnawing them clear with their teeth. A study on the longevity of this species revealed that aging Weddell seals whose teeth had worn down could no longer perform this task, so the durability of their teeth ultimately determined how long they lived before they suffocated under the ice.

Wild elephants also have their life spans limited by their teeth, which give out after around sixty-five years, should they survive other life challenges. As with human statistics, most animal longevity records far exceed the average lifespan; the maximum recorded for a captive elephant is around seventy years. Over an elephant’s lifespan it has six sets of molar-like teeth (premolars and molars), which erupt, one by one, in single file, from the rear of the jaw and migrate forward in a line as they wear over the years. No more than two molar-like teeth are ordinarily present in each dental quadrant at any given time, and they appear somewhat like glued together stacks of poker chips lying on their sides. Gradually, they break apart in flakes at the front of the jaws and are shed in fragments, as if they were dropping off the end of a conveyor belt. When the last molar is expended and food can no longer be chewed, elephants rapidly start to lose body condition from malnutrition. In captivity, aging elephants can be fed special diets if chewing food becomes a limiting factor.

In general, animals in captivity live significantly longer than their wild counterparts. The reasons include the absence of several major mortality denominators, such as predation and food supply, not to mention the availability of veterinary care.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anatomy | Animals |

| Bacteriology | Biochemistry |

| Bioelectricity | Bioinformatics |

| Biology | Biophysics |

| Biotechnology | Botany |

| Ecology | Genetics |

| Paleontology | Plants |

| Taxonomic Classification | Zoology |

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13113)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12045)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6349)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(6271)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(5818)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(5678)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4574)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(4536)

The Longevity Diet by Valter Longo(4463)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3930)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3852)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(3840)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(3796)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(3770)

Yoga Anatomy by Kaminoff Leslie(3724)

Barron's AP Biology by Goldberg M.S. Deborah T(3643)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(3597)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3540)

Yoga Anatomy by Leslie Kaminoff & Amy Matthews(3419)