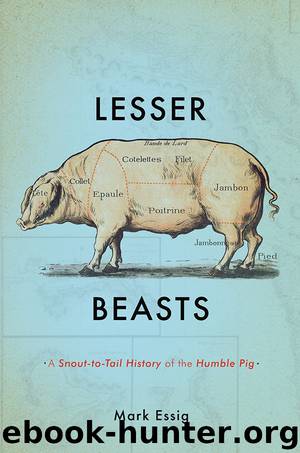

Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig by Mark Essig

Author:Mark Essig [Essig, Mark]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi, azw

Publisher: Basic Books

Published: 2015-05-04T22:00:00+00:00

Since the colonial period, Americans had been famous for consuming vast amounts of beef and pork, especially by comparison with the meat-starved peasantry of Europe. Statistics for early America are hard to come by, but we have some good clues. In many wills, husbands specified the amount of meat their widows were to be given. Widows typically received 120 pounds annually in 1700; a century later, that figure had risen to over 200 pounds. In the antebellum South, a typical ration for a slave was 3 pounds of pork per week, or about 150 pounds per year. Laborers in the North ate 170 pounds or more. After 1900, the statistics become more reliable. Between 1900 and 1909, per capita meat consumption in America was about 170 pounds, compared to 120 pounds in Britain, 105 in Germany, and 81 in France. “There are a great many ill conveniences here, but no empty bellies,” one Irishman in America wrote to his family back home.

The United States in 1900 saw itself as a nation of beef eaters, but that reflected aspiration more than reality: not until the 1950s did per capita beef consumption surpass that of pork. Pork was the meat of rural dwellers and the poor, while urbanites and the more affluent ate beef. This difference had to do with population density and technology. Beef was best eaten fresh, not salted, and artificial refrigeration at home was uncommon until after World War I. For a butcher to sell fresh meat from a nine-hundred-pound steer, he needed the large customer base that only an urban area could provide—and even in 1900 only two out of five Americans were city dwellers. Most lived in the country and stored their own meat supplies at room temperature. That meant salt pork.

Americans in the nineteenth century got most of their meat and fat from pigs. In his 1845 novel The Chainbearer, James Fennimore Cooper notes that a family is “in a desperate way when the mother can see the bottom of the pork-barrel.” (This sentiment underlies our expression “scraping the bottom of the barrel.”) Pickled pork lurked in nearly every dish. In Eliza Leslie’s Directions for Cookery, one of the most popular cookbooks of the nineteenth century, the recipe for pork and beans—“a homely dish, but . . . much liked”—called for a quart of beans and two pounds of salt pork, and her chowder contained as much pork as fish. One man, recalling his midwestern childhood, described a typical rural diet: “For breakfast we had bacon, ham, or sausage; for dinner smoked or pickled pork; for supper ham, sausage, headcheese, or some other kind of pork delicacy.” As a physician wrote in the magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1860, “The United States of America might properly be called the great Hog-eating Confederacy, or the Republic of Porkdom.”

Cheap American pork helped change the menu in Europe as well, as an important part of a growing international food trade that greatly improved the diet of Europe’s peasants and industrial workers.

Download

Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig by Mark Essig.mobi

Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig by Mark Essig.azw

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Amphibians | Animal Behavior & Communication |

| Animal Psychology | Ichthyology |

| Invertebrates | Mammals |

| Ornithology | Primatology |

| Reptiles |

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13052)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12029)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6336)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(6235)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(5785)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(5641)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4537)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(4507)

The Longevity Diet by Valter Longo(4445)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3905)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(3826)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3800)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(3771)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(3755)

Yoga Anatomy by Kaminoff Leslie(3701)

Barron's AP Biology by Goldberg M.S. Deborah T(3631)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(3579)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3515)

Yoga Anatomy by Leslie Kaminoff & Amy Matthews(3395)