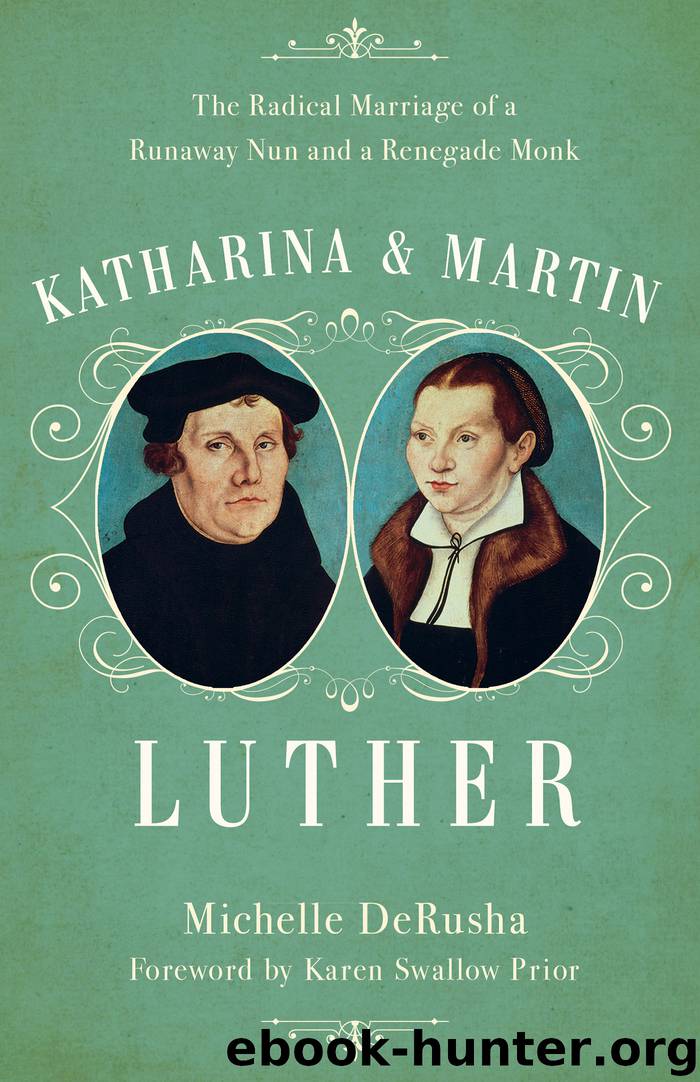

Katharina and Martin Luther by Michelle DeRusha

Author:Michelle DeRusha

Language: deu, eng

Format: epub

Tags: Martin and Katharina Luther;REL015000;REL053000;BIO018000

ISBN: 9781493406098

Publisher: Baker Publishing Group

Published: 2016-12-15T16:00:00+00:00

Shunned

Martin Luther wasn’t the first monk to marry, nor was Katharina the first nun. Augustinian monk Bartholomew Bernhardi married in 1521, and in 1522 the former monk Martin Bucer married a nun, Elisabeth Silbereisen.3 By 1524 more than seventy-five priests, forty-six monks, and thirty-three nuns had married in Germany.4 Nevertheless, laypeople distinguished between priests marrying and monks and nuns marrying. By the 1520s the former was somewhat acceptable; the latter was not.

Laypeople generally supported the idea of clerical marriage because they saw it as the best solution to the problem of concubinage among priests. Concubinage was defined as “unmarriage”—that is, unmarried couples living together as husband and wife—and it was a trend that had reached epic proportions among priests by the late Middle Ages. In some places, clerics appeared in public with their wives and children with hardly anyone batting an eye. Everyone knew concubinage among priests was morally wrong, but until Martin Luther came along with his marriage reforms, no one knew quite how to stop it.

As historian Wolfgang Breul observes, the “desacralization of priesthood and Luther’s desire to normalize the priestly estate formed the central social tenets of early Reformation propaganda. But what drove the change was the widespread criticism of the immoral practice of concubinage and the popular demand that priests marry.”5 In other words, ordinary citizens were fed up with priests living in sin, and they saw Luther’s reforms as the only way to halt the practice once and for all. The general population decided to support Luther’s reforms, and in doing so they ensured that those reforms would be upheld. It was an idea whose time had come.

In 1523, for example, Hersfeld’s town council issued a mandate threatening those who lived in “unmarriage” with physical punishment and banishment unless they married within fourteen days. Two of the priests in town married, which infuriated the local abbot. Up to this point, Abbot Krafft Myle von Hungen had been largely tolerant of the Reformation movement, but he saw the council’s mandate as a direct challenge to his ecclesiastical jurisdiction. As a result, he exiled the two married priests from Hersfeld, an action that enraged the townspeople, who stormed and destroyed both the office of the chancellor of the imperial monastery and the homes of the priests in town who were still living in concubinage. The laypeople took matters into their own hands, overthrowing the abbot’s authority and carrying out the council’s mandate.6

While laypeople generally condoned the marriages of priests, monastic marriages were another story. These marriages were considered transgressive, and the former monks and nuns who married were viewed as deviant. Many argued that monastic marriages would damage the institution of marriage, and by extension, society as a whole.

“While celibacy was expected of all clergy, and they made a clear vow of chastity, the vows made by the monastics, male and female, were held as more binding because of the separation of the monks and nuns from the rest of society,” says historian Marjorie Plummer. “It became

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Buddhism | Christianity |

| Ethnic & Tribal | General |

| Hinduism | Islam |

| Judaism | New Age, Mythology & Occult |

| Religion, Politics & State |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31333)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30934)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30889)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16624)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13053)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11903)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10907)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4537)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4424)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4399)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4279)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3845)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(3760)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(3634)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3569)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3516)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3437)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(3332)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3258)