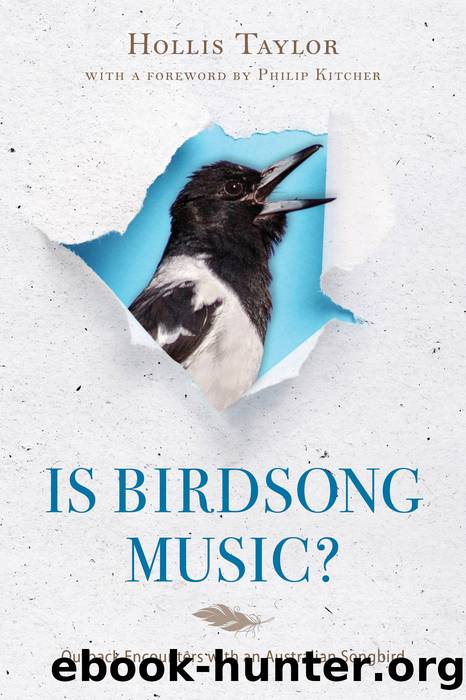

Is Birdsong Music? by Hollis Taylor

Author:Hollis Taylor

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Indiana University Press

Published: 2017-03-15T00:00:00+00:00

MIMICRY VERSUS ORIGINALITY

My interest here is to delve deeper into avian mimicry as a way of opening a discussion on the nature and definition of music. At least one-fifth of songbirds are vocal mimics.1 This makes it noteworthy that so few studies into the capacity have been conducted. Importations and appropriations occur in a variety of social situations and differ widely among species. Some birds mimic when stressed. Functional hypotheses propose that mimicry might assist in foraging efficiency, predator avoidance and defense, communication in dense habitat, song development, mate attraction, recruiting assistance for mobbingâand on it goes.2 Avian mimicry is poorly understood, and my own comparative studies of lyrebirds and pied butcherbirds suggest that a single functional accounting will likely never serve for all mimicking species.3

One wonders what motivates pied butcherbirds, who have a good-sized repertoire of their own, to incorporate the sonic constructs of others. It is unknown whether the signal of an alien species, when pasted into formal song or subsong, refers to that species, merely represents an appreciation of diverse sounds, or denotes something else altogether. Might it be an audio diary? Is it neophilia? Could it be a way of detaching a sound from its use value and branding it âpied butcherbirdâ? A bolder move might be to frame mimicry as a hyperintensification of a birdâs milieuâas a bird revealing their inner world at the same time as connecting to their total environment, sonic and otherwise, and perhaps even to a source of power. Yes, this smacks of religionâwhich is often interwoven with music. If we think of the cave painters at Lascaux as establishing and celebrating a metaphysical connection to prey and survival, as well as the surrounding cosmos, can we likewise allow an avian artist such a moment? Asking such a question is impossible for a scientist because at present there is no chance of answering it. A zoömusicologist, having thought the question but also lacking any expectation of an answer, perhaps has a responsibility to blurt it out nonetheless. We cannot overlook that some human cultures believe animals have souls and participate in ceremonies.4

On a lighter note, I have wondered if mimicry could be an amused glance at other speciesâan inside joke. Might mimicry be a narrative, and does it archive any extinct species? âOther orders of being have their own literatures,â supposes poet Gary Snyder. âNarrative in the deer world is a track of scents that is passed on from deer to deer with an art of interpretation which is instinctive. A literature of blood-stains, a bit of piss, a whiff of estrus, a hit of rut, a scrape on a sapling and long gone.â5 Detaching a sound from its original function is a process often assumed to be purely human. One assumes this degree of complexity and elaboration would be well beyond what is necessary for survival and reproduction.

Mimicry is equally relevant to understanding the human sound world. Composers are prolific borrowers, from one another and from their own past works; jazz improvisers are fond of quoting themes from both within and without their idiom.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Amphibians | Animal Behavior & Communication |

| Animal Psychology | Ichthyology |

| Invertebrates | Mammals |

| Ornithology | Primatology |

| Reptiles |

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14371)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12653)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(7324)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6938)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6932)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(6706)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5550)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5366)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5082)

The Longevity Diet by Valter Longo(5059)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4957)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4581)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4463)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(4435)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4375)

Yoga Anatomy by Kaminoff Leslie(4359)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4311)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4261)

Embedded Programming with Modern C++ Cookbook by Igor Viarheichyk(4173)