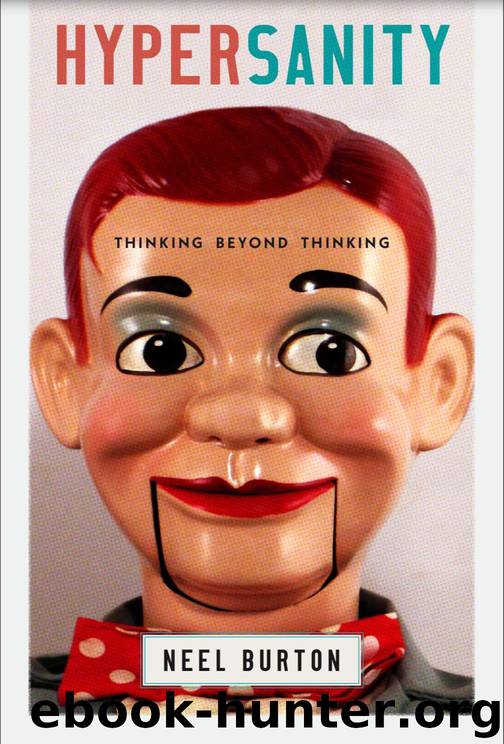

Hypersanity: Thinking Beyond Thinking by Burton Neel

Author:Burton, Neel [Burton, Neel]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Acheron Press

Published: 2019-06-14T16:00:00+00:00

13. Science

I f knowledge is so iffy, what of science? It is sometimes said that 90 percent of scientists who ever lived are alive today, so why is science not advancing by leaps and bounds?

To call a thing ‘scientific’ or ‘scientifically proven’ is to lend that thing instant credibility. Especially in Northern Europe, more people believe in science than in religion, and attacking science can raise the same old atavistic defences. In a bid to emulate, or at least evoke, the apparent success of physics, many areas of study have claimed the mantle of science: economic science, political science, social science, and so on. Whether or not these disciplines are true, bona fide sciences is a matter for debate, since there are in fact no clear or reliable criteria for distinguishing a science from a non-science.

What might be said is that all sciences (unlike, say, magic or myth) share certain assumptions which underpin the scientific method —in particular, that there is an objective reality governed by uniform laws, and that this reality can be discovered by systematic observation. A scientific experiment is basically a repeatable procedure designed to help support or refute a particular hypothesis about the nature of reality. Typically, it seeks to isolate the element under investigation by eliminating or ‘controlling for’ other variables that may be confused or ‘confounded’ with the element under investigation. Important assumptions or expectations include: all potential confounding factors can be identified and controlled for; any measurements are appropriate and sensitive to the element under investigation; and the results are analysed and interpreted rationally and impartially.

Still, many things can go wrong with the experiment. For example, with drug trials, experiments that have not been adequately randomized (when subjects are randomly allocated to test and control groups) or adequately blinded (when information about the drug administered/received is withheld from the investigator/subject) significantly exaggerate the benefits of treatment. Investigators may consciously or subconsciously withhold or ignore data that does not meet their desires or expectations (‘cherry picking’) or stray beyond their original hypothesis to look for chance or uncontrolled correlations (‘data dredging’). A promising result, which might have been obtained by chance, is much more likely to be published than an unfavourable one (‘publication bias’), creating the false impression that most studies on the drug have been positive, and therefore that the drug is much more effective than it actually is. One damning systematic review found that, compared to independently funded drug trials, those funded by pharmaceutical companies are less likely to be published; while those that are published are four times more likely to feature positive results for the products of their sponsors !

So much for the easy, superficial problems. But there are deeper, more intractable philosophical problems as well. For most of recorded history, ‘knowledge’ was based on authority, especially that of the Bible and white-beards such as Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Galen. But today, or so we like to think, knowledge is much more secure because grounded in observation. Putting to one side

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Thinking Clearly by Rolf Dobelli(10487)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9339)

Change Your Questions, Change Your Life by Marilee Adams(7780)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7706)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(7342)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5781)

Men In Love by Nancy Friday(5239)

Altered Sensations by David Pantalony(5103)

Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World – and Why Things Are Better Than You Think by Hans Rosling(4742)

The Confidence Code by Katty Kay(4260)

Thinking in Bets by Annie Duke(4226)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(4135)

The Worm at the Core by Sheldon Solomon(3486)

Why Buddhism is True by Robert Wright(3451)

Liar's Poker by Michael Lewis(3447)

Three Women by Lisa Taddeo(3433)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(3318)

Descartes' Error by Antonio Damasio(3277)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3268)