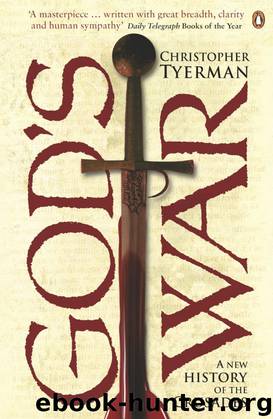

God's War: A New History of the Crusades by Tyerman Christopher

Author:Tyerman, Christopher [Tyerman, Christopher]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

Tags: Non-Fiction, Eurasian History, Military History, European History, Medieval Literature, 21st Century, Religion, v.5, Amazon.com, Retail, Religious History

ISBN: 9780674030701

Publisher: Belknap Press

Published: 2006-10-26T15:00:00+00:00

BYZANTIUM AND THE CRUSADE

No such thing as a ‘western attitude’ to Byzantium existed in the twelfth and early thirteenth century. It remains a myth of crusading historiography. Instead, a variety of responses was determined by region, status, the nature of the contact or its timing. On the levels of silks, saints, soldiers, trade and icons, exchange between western Europeans and the Greeks was habitual, customary and usually mutually beneficial. While differences in religious observance increasingly grated on a western ecclesiastical establishment eager to impose discipline and achieve uniformity, there were few awkward diplomatic or political absolutes, except, perhaps, for Byzantine foreign policy’s single-minded Palmerstonian pursuit of material interests rather than set alliances or ideological posturing, a stance that so irritated successive popes and crusade leaders. Over the politics of Italy, the Danube basin, the Balkans, the eastern Mediterranean, the Black Sea, Outremer and the Near East, western European powers and Byzantium competed, cooperated and coexisted. Whatever else, the scheme put to the crusader army at Zara spoke of contact, not alienation. It also recognized the implosion of Byzantine power since the death of Manuel I in 1180.22

Byzantium under Manuel I presented an image of universal power and a reality only little short of it. Although under Manuel’s predecessors Alexius I and John II the recovery from the defeats of the eleventh century – in Italy, Asia Minor, Syria and the Balkans – was territorially modest, by reasserting control over the ports of western Asia Minor and restoring the integrity of the Danube frontier, internal stability and the conditions for economic prosperity were secured. By 1180, the Byzantine empire included the Balkans south of the Danube, the islands of the Ionian and Aegean seas, Crete, Cyprus, western Asia Minor, Cilicia and the coastal ports of the southern Black Sea. A gold currency underpinned a comprehensive tax system and a centralized bureaucracy almost unknown further west. Diplomatically, the Greek emperor retained interests and correspondence from the Atlantic to the Persian Gulf, the Baltic to the Sahara Desert. Byzantine fleets operated from the Black Sea and the Adriatic to the Nile Delta. Satellite states sporadically festooned the frontiers, including Frankish Antioch and Seljuk Konya. Constantinople remained easily the grandest, largest and richest Christian city in the world, its population still about 375,000–400,000, six or seven times the size of Paris, despite its slums, inequalities of income, public affluence and private squalor, a magnet for trading communities from all over the Mediterranean and beyond. The imperial guard recruited from as far as Scandinavia and the British Isles; visitors came from Nubia. The quarters occupied by the commerical representatives of Venice, Pisa and Genoa were matched by a large Jewish settlement and a Muslim presence recognized by a number of mosques in the city.

The serenity of Manuel’s empire masked certain underlying problems. The Comnenan rulers since 1081 relied more than previous emperors on their own family rather than on state officials, on the army rather than the civilians. Power became increasingly focused on the person

Download

God's War: A New History of the Crusades by Tyerman Christopher.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Buddhism | Christianity |

| Ethnic & Tribal | General |

| Hinduism | Islam |

| Judaism | New Age, Mythology & Occult |

| Religion, Politics & State |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31348)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30947)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30906)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16656)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13072)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11914)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10915)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4551)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4427)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4410)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4288)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3854)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(3777)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(3647)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3575)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3526)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3446)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(3343)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3268)