Framing Majismo by Tara Zanardi

Author:Tara Zanardi

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Pennsylvania State University Press

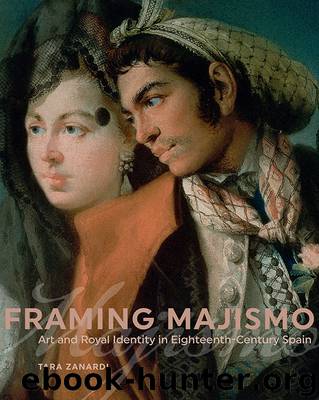

FIGURE 46

Francisco de Goya, The Laundresses, 1779–80. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. Photo: Album / Art Resource, N.Y.

Women not only sold, designed, and fabricated items, but they also participated in the consumption of goods. In The Fair of Madrid in the Plaza de la Cebada (ca. 1770–80), Manuel de la Cruz creates a cluttered scene in which both men and women sell and shop, suggesting that women’s buying power was of equal importance to men’s. The mantilla- and basquiña-clad woman in Goya’s The Crockery Vendor seems jovial and carefree, as she gently handles a ceramic bowl while a young man confidently leans back and offers a full view of his pottery. Tomlinson has proposed that the maja’s gesture and the inclusion of the elderly woman seated next to her make a strong case that there is more to this exchange than the sale of crockery.88 Goya has purposefully recalled a well-known procuress with artistic precedence in Dutch genre scenes. In Spain, however, the allusion was more specific. The older woman in this work refers to the theatrical character Celestina from Fernando de Rojas’s La Celestina, an early sixteenth-century play (1499–1502) highly esteemed by the artist’s contemporaries.

Celestina is frequently represented in Goya’s Los Caprichos. By playing on the majas’ assertive behavior, sexual allure, and Spanish dress, he locates these women between lighthearted flirtation and prostitution. In Goya’s Good Advice (fig. 47), a young girl listens to her procuress while fanning herself. A mantilla covers her eyes, adding to her mysterious appeal. While the veil wraps around her shoulders and a decorative black basquiña covers her legs, the maja’s bosom is highlighted. Charles Baudelaire understood the link between the procuress and her youthful companions, as seen in his discussion of Goya’s repetitive use of grotesque themes, including “those slim . . . Spanish girls . . . with ancient hags in attendance to wash and make them ready for the Sabbath . . . or it may be for the evening rite of prostitution, which is civilization’s own Sabbath!”89 In Hush (fig. 48), Goya depicts a Celestina figure and a maja; the young girl, covered by her dark mantilla, puts her finger to her lips, making the gesture to be quiet as she leans in toward the bent-over elderly woman. That this maja is nearly fully cloaked relates to criticism about the use of garments to conceal one’s identity and to reforms initiated by the government.90

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18634)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5478)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3677)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3546)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3531)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3454)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3363)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3326)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3182)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2920)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2918)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2884)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2728)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2720)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2673)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2641)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2587)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2581)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2513)