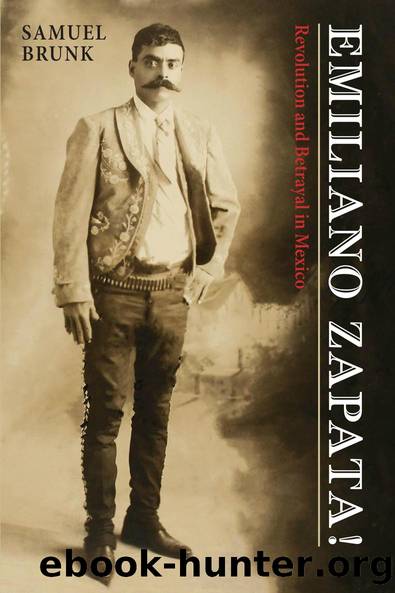

Emiliano Zapata! by Samuel Brunk

Author:Samuel Brunk [Brunk, Samuel]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Biography & Autobiography, Historical

ISBN: 9780826325136

Google: jp_RDAAAQBAJ

Publisher: University of New Mexico Press

Published: 2016-04-25T03:03:54+00:00

8The Road to Chinameca

MIXED EMOTIONS OR NOT, THE TASK AT HAND WAS plain: there was nothing to do but rebuild. Tlaltizapánââthe Mecca of Zapatismoââwhere Zapata again set up his headquarters, had also been ravaged by the Constitutionalists. The bodies of the latest massacre victims still lay in the streets when Zapata arrived, and the occupying force had dragged Amador Salazarâs corpse from the mausoleum, depriving it, some say, of its gold fillings and its charro suit. Some of the villageâs citizens, however, had managed to survive, and they now straggled down from the hills, ready to help âinject new life into that dead pueblo.â1

Zapata responded to the challenge of rebuilding Tlaltizapán and the rest of Morelos with a flurry of activity. By November 1916 he had commissioned his secretaries to create what would be called the Consultation Center for Revolutionary Propaganda and Unification, an organization that actually took shape at headquarters during the first days of 1917. Lead by DÃaz Soto y Gama, it was initially composed of fifteen of Zapataâs intellectual advisors, and its job was to propagandize, to deal with conflicts among jefes and between jefes and pueblos, and to help decide difficult matters of policy. It was also to direct a set of new juntasâcalled Associations for the Defense of Revolutionary Principlesâthat were being chosen in villages throughout the Zapatista world. These associations were to foment the revolution on the local levelâby holding meetings every Sunday to publicize Zapataâs laws and manifestos, by overseeing public education and the electoral machinery, and by explaining to the villagers that the armed struggle was undertaken on their behalf. More than merely an effort to rebuild, of course, this system was another attempt to temper military/civilian conflict and thus to strengthen ties to the villagers upon whom Zapatismo depended for support. It went further in this regardâat least on paperâthan anything Zapata had devised before, and with it he sought to keep his followers loyal. True to his principles, however, he would not coerce that loyalty at the expense of municipal democracy; instead he hoped that the local associations could secure it through persuasion, and thus enhance his control in the region.2

Complimenting this new organizational thrust were efforts to address some of the movementâs key issues more directly. In what was largely a gathering together of the previous dispositions of his headquarters on the subject, Zapata signed a law in March 1917 that outlined the rights and the obligations of villages and troops. âIt is urgent that we demonstrate with deeds,â this decree read, âthat the era of abuses has ended.â Another piece of legislation reinforced this insistence by seeking to stop Zapatista leaders from taking over nationalized properties for their own use, a practice that âwould give arms to the enemy so they could attack us, saying that before there were the hacendados and now there are the jefes.â As he had so many times in the past Zapata did what he could to reinforce the prerogatives of civil authorities.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Military | Political |

| Presidents & Heads of State | Religious |

| Rich & Famous | Royalty |

| Social Activists |

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37772)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23063)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19023)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18559)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13296)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12006)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8354)

Educated by Tara Westover(8037)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7462)

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden(5820)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5619)

The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy by James Cross Giblin(5263)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5132)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5082)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4942)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4793)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4340)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4085)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3948)