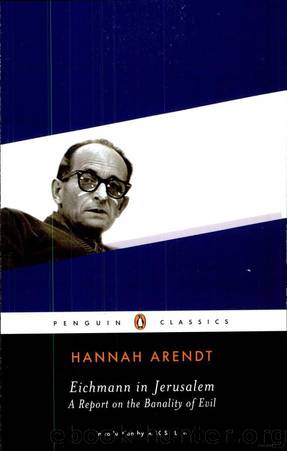

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil by Hannah Arendt

Author:Hannah Arendt [Arendt, Hannah]

Language: eng

Format: epub, azw3

Tags: Philosophy, General, Fiction, Literary

ISBN: 9781101007167

Google: yGoxZEdw36oC

Amazon: 0143039881

Publisher: Penguin

Published: 2006-09-22T04:00:00+00:00

IX : Deportations from the Reich—Germany, Austria, and the Protectorate

Between the Wannsee Conference in January, 1942, when Eichmann felt like Pontius Pilate and washed his hands in innocence, and Himmler’s orders in the summer and fall of 1944, when behind Hitler’s back the Final Solution was abandoned as though the massacres had been nothing but a regrettable mistake, Eichmann was troubled by no questions of conscience. His thoughts were entirely taken up with the staggering job of organization and administration in the midst not only of a world war but, more important for him, of innumerable intrigues and fights over spheres of authority among the various State and Party offices that were busy “solving the Jewish question.” His chief competitors were the Higher S.S. and Police Leaders, who were under the direct command of Himmler, had easy access to him, and always outranked Eichmann. There was also the Foreign Office, which, under its new Undersecretary of State, Dr. Martin Luther, a protégé of Ribbentrop, had become very active in Jewish affairs. (Luther tried to oust Ribbentrop, in an elaborate intrigue in 1943, failed, and was put into a concentration camp; under his successor, Legationsrat Eberhard von Thadden, a witness for the defense at the trial in Jerusalem, became Referent in Jewish affairs.) It occasionally issued deportation orders to be carried out by its representatives abroad, who for reasons of prestige preferred to work through the Higher S.S. and Police Leaders. There were, furthermore, the Army commanders in the Eastern occupied territories, who liked to solve problems “on the spot,” which meant shooting; the military men in Western countries were, on the other hand, always reluctant to cooperate and to lend their troops for the rounding up and seizure of Jews. Finally, there were the Gauleiters, the regional leaders, each of whom wanted to be the first to declare his territory judenrein, and who occasionally started deportation procedures on their own.

Eichmann had to coordinate all these “efforts,” to bring some order out of what he described as “complete chaos,” in which “everyone issued his own orders” and “did as he pleased.” And indeed he succeeded, though never completely, in acquiring a key position in the whole process, because his office organized the means of transportation. According to Dr. Rudolf Mildner, Gestapo head in Upper Silesia (where Auschwitz was located) and later chief of the Security Police in Denmark, who testified for the prosecution at Nuremberg, orders for deportations were given by Himmler in writing to Kaltenbrunner, head of the R.S.H.A., who notified Müller, head of the Gestapo, or Section IV of R.S.H.A., who in turn transmitted the orders orally to his referent in IV-B-4—that is, to Eichmann. Himmler also issued orders to the local Higher S.S. and Police Leaders and informed Kaltenbrunner accordingly. Questions of what should be done with the Jewish deportees, how many should be exterminated and how many spared for hard labor, were also decided by Himmler, and his orders concerning these matters went to Pohl’s W.V.H.A., which

Download

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil by Hannah Arendt.azw3

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Holocaust |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32563)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31962)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31945)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19105)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14394)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13342)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12036)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5375)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5225)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5105)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4923)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4790)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4612)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4538)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4483)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4224)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4119)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4106)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3973)