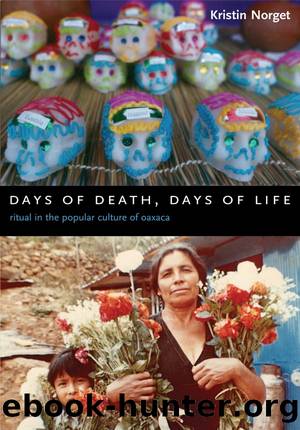

Days of Death, Days of Life by Kristin Norget

Author:Kristin Norget [Norget, Kristin]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, Sociology, Urban

ISBN: 9780231136884

Google: 0Hwped8ioXYC

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2006-01-15T05:28:38+00:00

DEATH PERFORMANCES

In Oaxaca, death raises the curtain on a social stage for the practical construction and dramatization of a moral community to which many of the living demonstrate a resolute commitment. Both novenario and Levantada de la Cruz followed most deaths I witnessed in Colonia San Juan, and although there were differences of detail in the ways these rites were practiced, that it was necessary to follow them was not in question. Some families could not in any way afford to bury deceased relatives, let alone host a novenario and Levantada, but they frequently appeared to defeat all odds by finding the necessary funds in the end. The emergence of the necessary resources time and again demonstrated many important features of the informal economy of the neighborhood; it also suggested that holding a novenario was widely seen as the âgoodâ and âproperâ way to mark the end of a personâs mundane existence. When I asked about these rites, many people explained that the Raising of the Cross ceremony was a buena manera (nice way) to finish the novenario; it is also clearly considered a ânice wayâ to commemorate the anniversary of someoneâs death.

The testimony that something is âniceâ or âright,â however, does not begin to convey the force or importance that participation in such ceremonies often had in peopleâs lives. What could compel so many community members to carry through with a full ten days of ritual activity, a period often requiring considerable economic expenditure and even sleepless nights of preparation, before hosting throngs of guests or spending several hours in prayer or other ritual activity? For a long while, the apparent urgency of such participation puzzled me. In time, however, I began to see that, in addition to the religious ends served by the novenario (the prayer for penance, the remembrance of the deceased as âone of the community of saints,â and so on), these rites served to conjure up a context of heightened customary âtraditionalâ ideal Oaxacan social interaction. Ritual had an ontological role; it was bound up with the very possibility of being, both individually and collectively. Special ritual language, highly coded modes of behavior, and many other nondiscursive ritual contents served to provide a context within which a collective narrative of experience could accumulate around the death event. Ultimately, this narrative served to organize individual perceptions; it conferred a sense of communal belonging on participants that overrodeâif only for a limited timeâpersonal interests and instrumental goals.

There were many striking cases of voluntaryâand often spontaneousâneighborhood cooperation in the context of funerals in Colonia San Juan that contradicted the realities of conflict and tension prevailing in other spaces of social interaction. For example, when Manuel was killed, many people in the neighborhood joined resources and forces to ensure that, despite the tragic accident that had killed him, he met a âgoodâ end. At the time that he was hit, Manuel was fifty-nine, half-blind, and an unemployed widower with four grown children. Manuelâs married daughter, Concepción, her husband, and

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Baha'i | Cults |

| Demonology & Satanism | Eckankar |

| Egyptian Book of the Dead | Freemasonry |

| Messianic Judaism | Mysticism |

| Scientology | Theism |

| Tribal & Ethnic | Unitarian Universalism |

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6744)

Breaking Free by Rachel Jeffs(4216)

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (Translated) by Svatmarama(3327)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(3262)

Member of the Family by Dianne Lake(2350)

The Tao of Physics by Fritjof Capra(2272)

The Psychedelic Gospels: The Secret History of Hallucinogens in Christianity by Jerry B. Brown(2149)

The Road to Jonestown by Jeff Guinn(2063)

Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief by Lawrence Wright(1978)

Going Clear by Lawrence Wright(1962)

Uriel's Machine by Christopher Knight(1898)

The Grand Grimoire: The Red Dragon by Author Unknown(1805)

The Gnostic Gospel of St. Thomas by Tau Malachi(1793)

Key to the Sacred Pattern: The Untold Story of Rennes-le-Chateau by Henry Lincoln(1625)

Animal Speak by Ted Andrews(1618)

The Malloreon: Book 02 - King of the Murgos by David Eddings(1589)

Waco by David Thibodeau & Leon Whiteson & Aviva Layton(1558)

The New World Order Book by Nick Redfern(1548)

The Secret History of Freemasonry by Paul Naudon(1492)