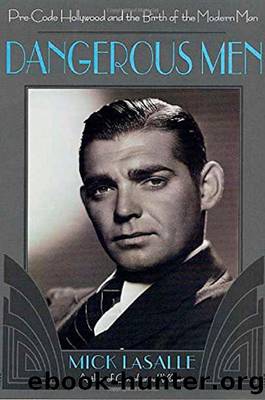

Dangerous Men: Pre-Code Hollywood and the Birth of the Modern Man by Mick Lasalle

Author:Mick Lasalle [Lasalle, Mick]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Non-Fiction, Performing Arts, Film, History & Criticism, Social Science, Men's Studies

ISBN: 9780312283117

Google: S_iyAwAAQBAJ

Amazon: 0312283113

Publisher: Macmillan

Published: 2002-11-02T00:00:00+00:00

9

“No Longer a Man’s World”

MODERN MEN LIKED modern women. Pre-Code movies consistently presented admirable and heroic characters who—even when they looked like old-fashioned he-men—were broad-minded, tolerant, and appreciative when it came to women. These fellows weren’t necessarily easy to get along with, but at least they weren’t virtue-obsessed or judgmental. Except in Greta Garbo movies, which were in their own category, heroes did not barge out in a huff when they heard the heroine wasn’t a virgin.

The pre-Code era, a great age for men, was also the great age for women in American cinema, a fact that should not be overlooked. In this period, there was a rich array of talented and charismatic actresses making films that reflected the expanding role of women in modern America. Their movies dealt with changing mores regarding sex, romance, and marriage, and they showed women in the workplace, sometimes as educated professionals. The films, which echoed the public’s changing attitudes, would grow yet more freethinking and daring until the ax of censorship fell in July 1934.

Men’s films reflected those same changes. That men and women were equal partners in the adventure of life was not something asserted by these movies, but something so understood as to need no asserting. Anyone looking for a rare pocket of film history in which male-female relationships were presented as healthy, sane, and lively should look no further than the years 1929 to 1934.

Yet in acknowledging this, it’s important not to sweep a few facts under the rug. One item too big for any rug is the era’s indelible image of James Cagney hitting Mae Clarke in the face with a grapefruit in The Public Enemy (1931). Even if we counter that by saying that the jolly relationship between William Powell and Myrna Loy in The Thin Man (1934)—or Astaire and Rogers in Flying Down to Rio (1933)—was more in the spirit of the era than the grapefruit incident, there are yet other moments to account for: Cagney’s dragging Mae Clarke by the hair in Lady Killer (1933); Chester Morris working over Jean Harlow in Red-Headed Woman (1932), though she seems to like it; and the comic climax of Bureau of Missing Persons (1933), in which Pat O’Brien beats up greedy ex-wife Glenda Farrell, offscreen, as we hear the sounds of crashing and breaking.

Certainly, in a way that’s lost to us, Depression audiences seemed to get a kick out of the sight of men and women physically fighting, whether it was Norma Shearer and Robert Montgomery’s knock-down-drag-out in Private Lives (1931) or bad guy Gable’s one-punch knockout of Barbara Stanwyck in Night Nurse (1931). Audiences, for that matter, also enjoyed the sight of women fighting one another. Yet even if we see some of these encounters as manifestations of an underlying assumption that women could give as well as they got, that was clearly not the whole story.

Cagney himself was self-conscious about his image as a woman-beater and would always go out of his way to assure people he wasn’t really that sort of guy.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(4433)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(3918)

The Perils of Being Moderately Famous by Soha Ali Khan(3782)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(3582)

Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee(2985)

The 101 Dalmatians by Dodie Smith(2935)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(2739)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(2674)

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald by J. K. Rowling(2543)

How Music Works by David Byrne(2525)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(2416)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(2415)

The Mental Game of Writing: How to Overcome Obstacles, Stay Creative and Productive, and Free Your Mind for Success by James Scott Bell(2393)

Wildflower by Drew Barrymore(2117)

Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema by Anne Helen Petersen(2109)

Casting Might-Have-Beens: A Film by Film Directory of Actors Considered for Roles Given to Others by Mell Eila(2071)

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting by Syd Field(2057)

Robin by Dave Itzkoff(2005)

The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Reader by H.P. Lovecraft(1976)