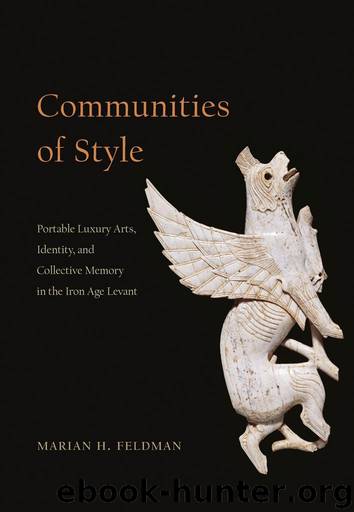

Communities of Style by Marian H. Feldman

Author:Marian H. Feldman [Feldman, Marian H.]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Published: 2014-10-29T16:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER 5

The Reuse, Recycling, and Displacement of Levantine Luxury Arts

The reinscription of some of the Levantine metal bowls, along with their appearance in what must clearly be secondary contexts, such as the Etruscan and Greek burials, point to multiple circulatory patterns for these and other Levantine artworks.1 Likewise, the discovery near the pan-Hellenic sanctuary of Olympia of a Levantine bowl inscribed for an owner bearing a West Semitic name2—whether a bowl like this was left as a votive, as most scholars assume, or acquired by temple officials for ritual activities, as proposed by Ingrid Strøm3—suggests a secondary usage in a context associated with the sanctuary. Such circulation has been acknowledged in the scholarship for many years, prompting the examination of so-called Orientalizing trends in eighth-century Greece and Italy. Yet only more recently has attention been turned to the variations and precise articulation of this circulation, complicating what had been previously understood in rather simplistic terms as the natural by-product of commercial Phoenician activity.4 This chapter explores some of these complex social histories through a series of case studies, each of which presents slightly different circulatory trajectories. Keeping in mind the blurring of distinctions between purportedly “Phoenician,” “North Syrian,” “Aramaean,” and “Luwian/Neo-Hittite” material culture during the ninth through seventh centuries, these variable circulation patterns provide further caution regarding singular models of homogeneously defined ethnic groups spreading knowledge (and art styles) by means of a mercantilism constructed through the lens of modern European capitalism. My purpose is not to redefine the history of Phoenician/Levantine movement in the Mediterranean but rather to bring to the fore the complicated nature of the situation, and to encourage case-by-case analysis of mobile arts rather than one-size-fits-all models. In this respect, I seek to build a bottom-up set of narratives derived from individual artifacts rather than a top-down model seeking to explain the presence of all circulating artifacts. In so doing, I propose differing accretions of value and meaning within the artifacts’ changing contexts of use, which in turn generate new possibilities of community formation and identity.

Each of the cases examined in this chapter presupposes some displacement of the artworks from the place of their original manufacture to that of their deposition. The element of disjuncture or rupture manifests in varying means of reuse and recycling in the new context.5 While the “biographies” of Levantine artworks prior to their deposition can be hard to trace, careful analysis of the stylistic and technical features of both individual objects and assemblages of like objects can reveal strong circumstantial evidence for aspects of the earlier trajectories of their social lives. It is not my aim to pinpoint the locations of initial manufacture, an endeavor undertaken by most studies of these works with varying degrees of satisfactory results. Nonetheless, each object or group of objects bespeaks displacement in some way or another. Sometimes these displacements involve crossing geocultural areas, sometimes they involve moving across sociopolitical strata, and sometimes they involve both. By employing the term displacement, I intend no devaluing of the subsequent uses of these pieces.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18629)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5476)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3677)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3543)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3529)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3452)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3360)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3325)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3178)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2918)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2918)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2883)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2726)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2719)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2670)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2640)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2587)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2579)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2512)