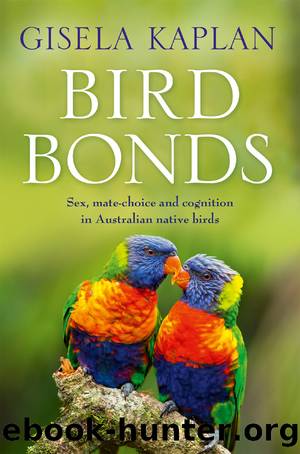

Bird Bonds by Gisela Kaplan

Author:Gisela Kaplan

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Pan Macmillan Australia

Published: 2019-07-14T16:00:00+00:00

Fig. 8.1 Kookaburra family sitting together for an afternoon chorus. There had been no apparent threat. It just seemed as if the kookaburras were enjoying a family gathering. Possibly some such choruses, when not performed at the loudest range, are an expression of group affiliative sentiments and these may have nothing to do with fear, threats or aggression.

One might find Lorenz’s assumption of the link between triumph ceremony and aggression a little far-fetched, but it raises important questions about closely bonded families and pairs. We rightly call such bonds affiliative, and Dunbar based his social brain hypothesis on the assumption for a greater need of social communication in bonded groups. This is an important suggestion, but it also may invite a romanticised view of living in families or groups. Not all instances of communication are expressions of affiliative needs. On the contrary, it can and has been argued that it is not ‘love’ but the daily struggle to survive in a group that fosters greater demands on the brain. To get a share of resources and be able to reproduce at some stage might require the learning of a set of strategies in potential conflict situations.

Many have argued that group/partner living is not always blissful at all and proponents of such ideas claim, not without justification, that conspecifics often have little choice other than to stay together. They may constantly compete with one another for limited resources and so continually need to challenge their cognitive ability through a form of a cognitive arms race (Barrett and Henzi 2005; Byrne and Bates 2010). This basic premise, commonly termed Machiavellian intelligence (Byrne and Whiten 1989), relies on the notion that most animals are unwilling collaborators, forced to live in groups to minimise the risks of predation and infanticide (in primates) from conspecifics (van Schaik and Kappeler 1997). This group living then allegedly required the adoption of behaviour, such as grooming and negotiation, to allow individuals to coexist, and to more easily find potential mates (Barrett and Henzi 2005). Yet, competition for food and for mates remains and gives rise to manipulation, deceit, as well as sub-alliances that may play each other off, or splinter off to form competing groups. In white-winged choughs, Corcorax melanorhamphos, for instance, one group may destroy the nests of another group, a behaviour called sabotage (Heinsohn 1988), and one group may even try to steal youngsters from another in order to make their group stronger and their territory more easily defendable (Heinsohn 1991). Even within groups, the mutual support that cooperative breeders are supposed to provide via helpers may not, in reality, always work in constructive ways: juvenile helpers may only pretend to help and gulp down the food they have found themselves (Kaplan 2015).

Group conflicts and competition in relatively stable groups have been confirmed in many species but the opposite case has not been made as well or as often, namely that positive observable behaviour, such as preening, may lead to robust reconciliation (Strier et al. 2002; Silk et al.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Excursion Guides | Field Guides |

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4120)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(3755)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3516)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3234)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3183)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3139)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(2950)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(2854)

Hedgerow by John Wright(2776)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(2766)

Origin Story by David Christian(2683)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(2665)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(2661)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(2645)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(2587)

Water by Ian Miller(2582)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2453)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2363)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2335)