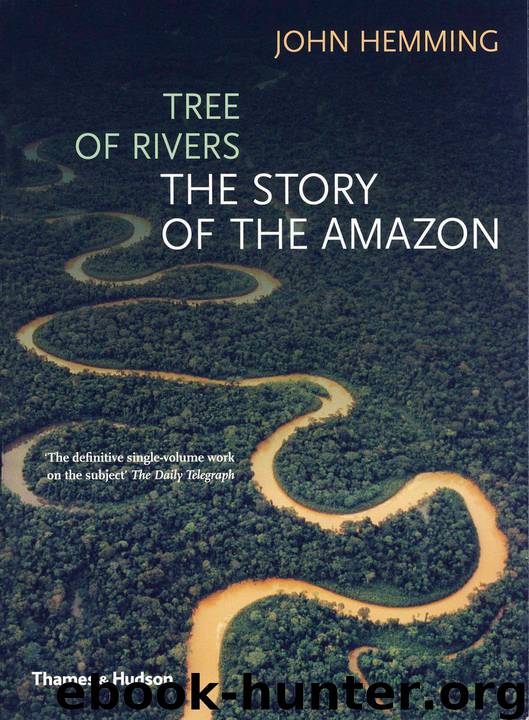

Tree of Rivers: The Story of the Amazon by John Hemming

Author:John Hemming [Hemming, John]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Brazil, rubber, ecology, amazon, environment, South America, deforestation, rain forest, explorers, naturalists

Publisher: Thames & Hudson

Published: 2012-10-23T23:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Black Side of Rubber

The rubber bonanza exacted a heavy price – but the victims were human, not environmental. Fortunately, tapping does not destroy rubber trees. Seringueiros’ clearings and trails were mere scratches on the immensity of the Amazon forests and, since movement was all by river, there were no roads apart from the Madeira-Mamoré railway. So there was little deforestation. Fish, game and particularly turtle resources were depleted to feed and light the lamps of the rubber men and their masters in the cities. But the greatest cost of ‘white gold’ was in the misery of those who extracted it.

In the early decades of the boom, from the 1850s to 1880s, rubber-tapping was a form of liberation for the Amazonian working class. Because there was an acute labour shortage, caboclos could demand good treatment if they were to continue to work in plantations, public works or as boatmen. Hundreds chose to migrate up the tributaries in search of rubber. The British consul in Pará described this exodus, in 1870. ‘A family gang or a single man erect a temporary hut in the forest and, living frugally on the fruit and game which abound and their provision of dried fish and [manioc] farinha, realize in a few weeks such sums of money, in an ever-ready market, with which they are able to relapse into the much-coveted idleness and enjoy their easy gains until the dry season for tapping the rubber-trees … returns.’1 At first the provincial authorities resented this drain on their labour supply. One president of Pará lamented that the white-gold-rush ‘is leading into misery the great mass of those who abandon their homes, small businesses and even their families to follow it. They surrender themselves to lives of uncertainty and hardship, in which the profits on one evening evaporate the following day.’2 Such condemnation, however, changed when presidents started to appreciate the value of rubber exports. All that money easily wiped out any scruples about how it was acquired.

The system was lubricated by itinerant traders known as regatão (‘hawker’ or ‘haggler’). A regatão took his boat far up forested rivers and sold essential goods to seringueiros in return for their rubber crop. He of course made the maximum profit, selling shoddy goods at grotesquely inflated prices and buying cheaply. There was much official fury against the regatão, sometimes tinged with xenophobia because many were Levantine or Jewish. But these traders supplied seringueiros with the few goods they needed as well as some companionship, and they provided an outlet for the rubber. As the boom progressed, individual hawkers gave way to better-organized aviadores (‘suppliers’), often equipped by and working for the big rubber companies in Manaus or Belém. Aviadores were just as shameless as regatão traders in exploiting tappers, but some were also liked because they brought supplies and friendship to isolated workers.

Some indigenous tribes entered the rubber system voluntarily, others were forced into it, yet others fled from the madness deeper into their forests. The Mundurukú was

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anatomy | Animals |

| Bacteriology | Biochemistry |

| Bioelectricity | Bioinformatics |

| Biology | Biophysics |

| Biotechnology | Botany |

| Ecology | Genetics |

| Paleontology | Plants |

| Taxonomic Classification | Zoology |

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14361)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12649)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(7320)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6933)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6929)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(6697)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5545)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5364)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5079)

The Longevity Diet by Valter Longo(5057)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4956)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4571)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4459)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(4433)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4375)

Yoga Anatomy by Kaminoff Leslie(4358)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4309)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4259)

Embedded Programming with Modern C++ Cookbook by Igor Viarheichyk(4171)