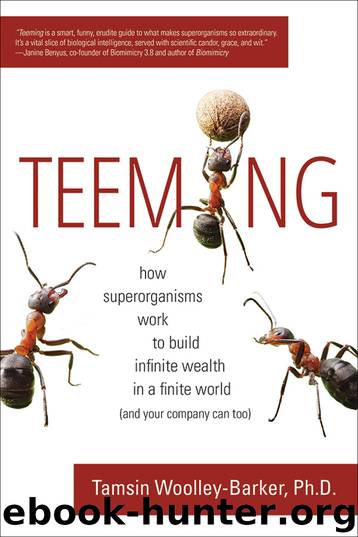

Teeming by Tamsin Woolley-Barker

Author:Tamsin Woolley-Barker

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781940468433

Publisher: Lightning Source Inc.

Published: 2017-08-30T04:00:00+00:00

Chapter Eighteen

It’s Sexy Time!

If you watch animals objectively for any length of time, you’re driven to the conclusion that their main aim in life is to pass on their genes to the next generation.

—DAVID ATTENBOROUGH

In San Diego County, where I live, tiny isolated pools appear briefly on the claypan mesas after a winter rain. These ephemeral oases explode with fevered activity, but quickly dry up. The creatures that live here move fast. Water fleas—tiny aquatic crustaceans—flourish briefly, and they’ve evolved a special strategy to capitalize on these short-lived bonanzas.

In the dry times, the water fleas’ tiny eggs lie in the dust—sometimes for many long, hot years. When the rains finally come, these cysts hatch instantly into female water fleas, which get to work eating. The fleas clone themselves like crazy, making more little females exactly like themselves just as fast as they can. Why fix it if it ain’t broke, and why waste time looking for a mate? But as the pool dries up, the water warms and oxygen dwindles. Suddenly, BAM! It’s sexy time! The fleas switch to sex. Like magic, the sex ratio changes to favor males and mating begins. Instead of making baby water fleas, though, they scramble new combination of genes and produce eggs that will lie dormant until the next rains. Their strategy shifts from imitation to experimentation. The fleas will try anything and everything to regenerate their future.

Let’s talk about sex, baby. It’s an old and widespread practice, so presumably sex is good for something. Fossilized evidence of multicellular sex (talk about caught in the act) is at least a billion years old. It does a lot of useful things—breaking up bad genetic combinations for one thing—if a cool new mutation comes along, mixing it into some different combinations might give it a better chance to work. Mixing genes also confuses parasites—it’s harder to hit a moving target. If you have a population of snails, where some are sexual mixers and others are asexual cloners, infection spreads rapidly among the clones, which eventually blink out and disappear. Of course, it’s also possible they just hated their lives, and gave up without a fight. Meanwhile, the ones getting busy dodge infection easily, by continually tweaking their defenses. Sex is the now-you-see-me-now-you-don’t anti-microbial strategy.

Sex is also the source of most novelty and innovation. Some poor species are deprived of it altogether, but asexual cloners still get a dash of novelty here and there from sloppy DNA copying. Small errors—mutations—accumulate, and some work better than others. The population gradually shifts. It’s slower and more random than sex (no really!), and most mutations are harmful or do nothing at all. Still, they do introduce some variation—the doors to the Adjacent Possible. Different branches of the evolutionary tree mutate at different rates, by the way—each tuned over millions of years to optimize the chance of hitting the opportunity lotto.

Sex is a powerful way to acquire diversity, and it’s especially lively where one habitat transitions into another. Such edges are simmering hotbeds of innovation—alchemical cauldrons where genes and habitats collide.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14389)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12659)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(7347)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6944)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6941)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(6725)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5558)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5370)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5096)

The Longevity Diet by Valter Longo(5064)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4969)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4588)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4472)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(4445)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4383)

Yoga Anatomy by Kaminoff Leslie(4363)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4322)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4272)

Embedded Programming with Modern C++ Cookbook by Igor Viarheichyk(4179)