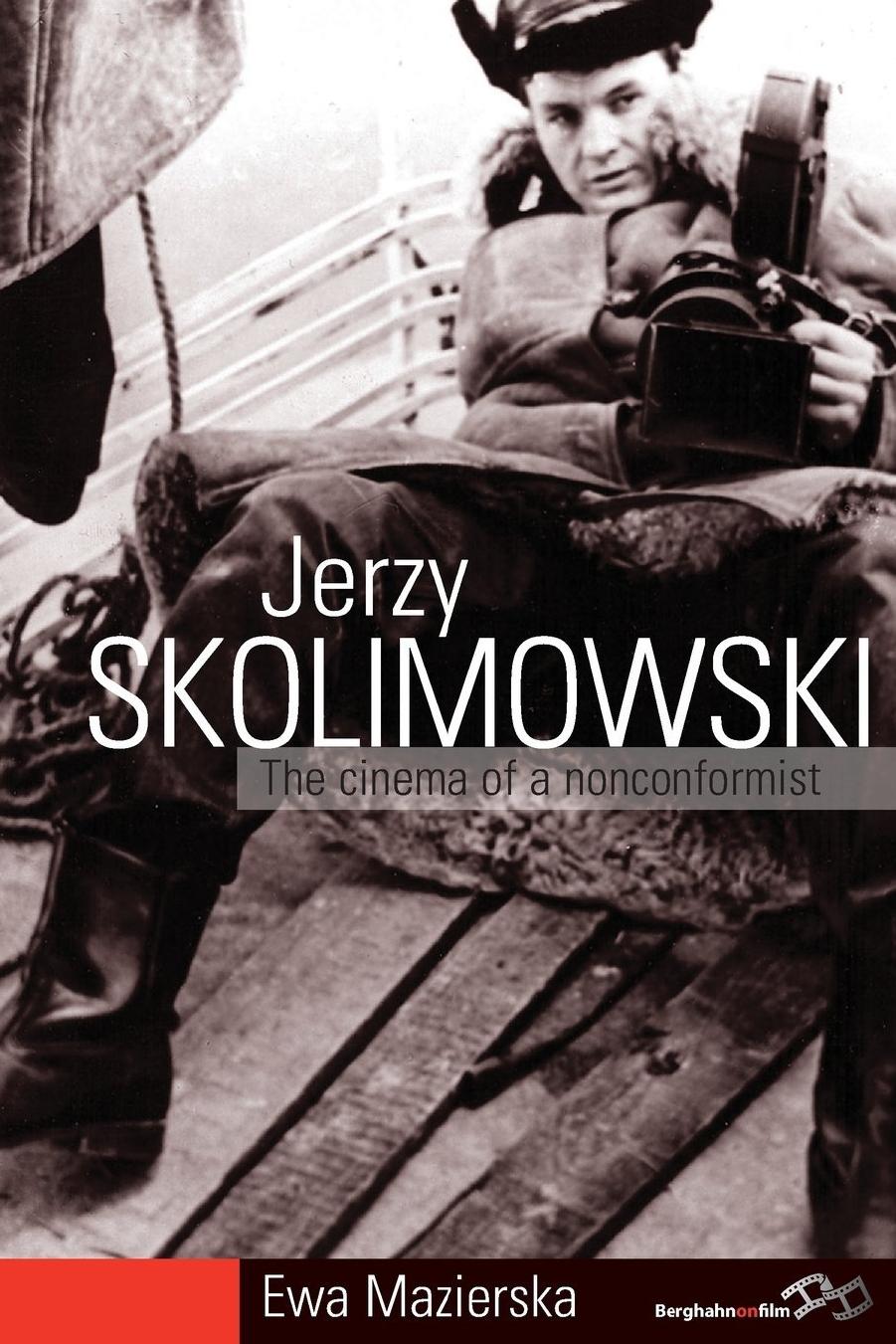

Jerzy Skolimowski: The Cinema of a Nonconformist by Ewa Mazierska

Author:Ewa Mazierska [Mazierska, Ewa]

Language: eng

Format: azw3, pdf

Publisher: Berghahn Books

Published: 2013-09-15T00:00:00+00:00

Water

He did not picture life's ocean, as do poets, all astir with stormy waves. No, he saw it in his mind's eye as smooth, without a ripple, motionless and translucent right down to the dark sea bed. He saw himself sitting in a small unsteady boat, staring at the dark silt of the sea bottom, where he could just discern shapeless monsters, like enormous fish. These were life's hazards â the illnesses, the griefs, madness, poverty, blindnessâ¦

(Ivan Turgenev, Spring Torrents)

Water is a frequent setting in Skolimowski's films and his films are âawashâ with water metaphors. His characters live on or near water (The Lightship, The Shout), travel on water (Ferdydurke), work with water (Deep End), study water life (Leszczyc in Identification Marks: None) and like to bathe in it (Little Hamlet, Barrier, Deep End). Moreover, the protagonist of the âLeszczyc tetralogyâ has a name associated with water, as âleszczâ in Polish means âbreamâ. Yet unlike PolaÅski, Skolimowski is not associated with the mise-en-scène of water, most likely because PolaÅski began his career with a distinctive take on water, while Skolimowski elaborated it for a longer time. Large areas of water feature more prominently in his later films, while in his early productions water rather drips than floods. Take his early Little Hamlet, in which the Polish Ophelia has a bath in a humble bathtub and most likely drowns there. By contrast, in PolaÅski's cinema vast areas of water already appear in his early shorts and his feature debut, Knife in the Water.

Both PolaÅski and Skolimowski represent water as a liminal space â a passage to a different reality. However, in Skolimowski's films water not so much signifies moving to the realm of fantasy (pure fantasy rarely appears in his films), as a transition between different stages of life, including the passage between childhood and maturity, and life and death. The only possible exception is in Ferdydurke, where at the end of the film Józio embarks on a boat, escaping everything which he encountered during his peregrinations as a schoolboy. This trip signifies Józio finally leaving the realm of childhood and becoming a man, as well as his parting from Poland. These associations are suggested by the name of the boat, âTrans-Atlantykâ, which is also the title of a famous, semi-autobiographical novel by Witold Gombrowicz, who left Poland on a ship of this name and landed in Argentina. Leaving Poland, for Gombrowicz and Skolimowski, not only means parting from the geographical location but also from the historical and cultural entity â the prewar Poland of decadent aristocracy and disappearing âsimple peasantsâ. However, even if we regard the boat in Ferdydurke as a vehicle of a metaphysical journey, this journey lacks the suggestiveness of the two men from PolaÅski's Dwaj ludzie z szafÄ (Two Men and a Wardrobe, 1958) disappearing in the water. Moreover, the viewer must have some minimal literary knowledge to grasp the meaning of Józio's final trip.

There is no sea or any other large areas of water in Skolimowski's feature debut, Identification Marks: None, but the sea is often talked of by the characters.

Download

Jerzy Skolimowski: The Cinema of a Nonconformist by Ewa Mazierska.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Coloring Books for Grown-Ups | Humor |

| Movies | Performing Arts |

| Pop Culture | Puzzles & Games |

| Radio | Sheet Music & Scores |

| Television | Trivia & Fun Facts |

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5170)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(4641)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(4389)

The Perils of Being Moderately Famous by Soha Ali Khan(4216)

The 101 Dalmatians by Dodie Smith(3506)

Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee(3461)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(3431)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3301)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3259)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3060)

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald by J. K. Rowling(3055)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(2997)

The Mental Game of Writing: How to Overcome Obstacles, Stay Creative and Productive, and Free Your Mind for Success by James Scott Bell(2897)

4 - Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by J.K. Rowling(2700)

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting by Syd Field(2636)

The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Reader by H.P. Lovecraft(2557)

Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema by Anne Helen Petersen(2515)

Wildflower by Drew Barrymore(2484)

Robin by Dave Itzkoff(2437)