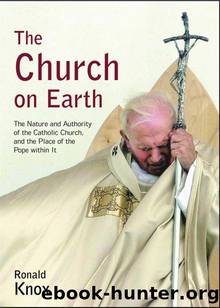

Church on Earth by Knox Ronald A

Author:Knox, Ronald A. [Knox, Ronald A.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Sophia Institute Press

Published: 2012-10-19T04:00:00+00:00

Chapter Ten

The Church has judicial authority

We have already considered one kind of jurisdiction which the Catholic Church enjoys â namely, that which is exercised in the sacrament of Confession, or, as theologians say, in the internal forum. Even if the Church had no need, in her corporate capacity, of judges and of tribunals, one court would still remain: the little court of two persons that meets in the confessional. In that court, Almighty God is Himself the Prosecutor, is Himself (in the person of His priest) the Judge. The penitent is himself the defendant, himself Kingâs Evidence of his own misdoings.

Let us suppose a layman and a missionary priest are shipwrecked on a desert island, within the limits in which the priestâs faculties hold good. They may live there for years, cut off from the rest of Christendom. That spiritual court can still be set up, that sacramental jurisdiction can still be exercised, month after month, year after year. It is part of the Churchâs ministerial office.

But the judicial authority of the Church is not confined to the internal forum, is not bounded by the horizon of the confessional. The Church is a body corporate, with her own trust-deeds and her own laws; she must, then, enjoy judicial powers in this corporate capacity of hers, whenever doubt or dispute arises. And these, it is to be observed, are quite distinct from, and exist side by side with, the judicial powers of the state.

Heretics at various times, with a tendency that may roughly be described as Anabaptist, hold that the state, as an unsupernatural institution, has no jurisdiction over Christian men; emancipated from the bondage of the flesh, they owe obedience to none save spiritual superiors. The Catholic Church has always recognized the simultaneous existence of two streams of authority, each derived ultimately from God: secular authority, which belongs by right to the state, and ecclesiastical authority, which belongs by right to the Church. True, St. Paul does his best to dissuade Christians from going to law with one another before the heathen courts of his day; they ought rather to submit their differences to arbitration by members of their own Body.21 But it is evident that this is only a rebuke to the litigiousness of his converts, not a denial of the competence of those heathen courts to which he alludes. The powers that be, even when Nero is the worldâs autocrat, are ordained by God.

Ecclesiastical jurisdiction, then, is not a substitute for state action; but the Church, as a perfect and independent society, has the right, within her own sphere, to judge her subjects. Such powers are necessary even for the due exercise of her teaching authority. If a priest (such as Arius) or a bishop (such as Nestorius) is accused of heterodoxy, it is not enough, as a rule, for the Church to condemn in the abstract the teaching supposedly given. To safeguard the faith of the simple, she must further determine whether the accused person has in

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Resisting Happiness by Matthew Kelly(3341)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3031)

Day by Elie Wiesel(2786)

Designing Your Life by Bill Burnett(2748)

The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein(2345)

Human Design by Chetan Parkyn(2075)

The Supreme Gift by Paulo Coelho(1981)

Angels of God: The Bible, the Church and the Heavenly Hosts by Mike Aquilina(1969)

Jesus of Nazareth by Joseph Ratzinger(1811)

Hostage to the Devil by Malachi Martin(1803)

Augustine: Conversions to Confessions by Robin Lane Fox(1774)

7 Secrets of Divine Mercy by Vinny Flynn(1747)

Dark Mysteries of the Vatican by H. Paul Jeffers(1723)

The Vatican Pimpernel by Brian Fleming(1703)

St. Thomas Aquinas by G. K. Chesterton(1635)

Saints & Angels by Doreen Virtue(1606)

The Ratline by Philippe Sands(1580)

My Daily Catholic Bible, NABRE by Thigpen Edited by Dr. Paul(1503)

Called to Life by Jacques Philippe(1481)