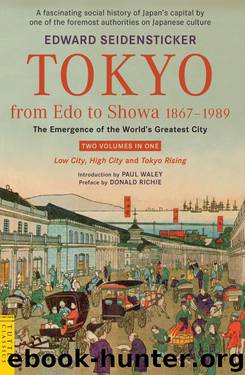

Tokyo from Edo to Showa 1867-1989 by Edward Seidensticker

Author:Edward Seidensticker [Seidensticker, Edward G.]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

Publisher: Tuttle Publishing

Published: 2011-07-19T16:00:00+00:00

Entrance to the new subway in Asakusa

The subway company put up high buildings at each of its two original terminuses, Asakusa and Ueno. (For the Asakusa terminus, see page 353.) The Ueno terminus had a department store, on its front a clock, illuminated at night, said to be the largest in the world. It was some twenty meters in diameter. Both buildings have been torn down in the years since the war. Subway people do not seem to have had the heads for retailing possessed by the people of the surface railways.

The Ginza line, not quite nine miles long, was the only line in existence during the war years. Construction did not begin on a second line until 1951, when another reconstruction of the city was underway. Thus well over 90 percent of the splendid system we have today is postwar. Though not badly planned, insofar as it was planned at all and not given over to mercantile ambitions, the Ginza line was not ideally planned to alleviate congestion on the National Railways. Shinjuku was growing more rapidly than Shibuya and would have been a better terminus.

The National Railways continued to provide faster transportation from all commuter transfer points except Shibuya than did the subway. Yet it probably helped to keep Ginza at the center of things, and for this we must be grateful. Rapid transit had terminated just south of Ginza when the railway line to Yokohama opened in early Meiji and skirted it when, early in Taishō, the National Railways began service through to Marunouchi. Now it ran north and south under the main Ginza street. Another change in the transportation system favored the suburbs. Buses grew numerous and important, and, most naturally, the trolley system entered upon the decline that has in recent years brought it near extinction. With the trolley system and the railways heavily damaged by the earthquake, large numbers of little companies sprang up to take people to and from the suburbs—almost two hundred of them, mostly short-lived, in two months. Motorized public transportation was in much confusion. In the mid-thirties there were still several dozen private bus lines, in competition with one another and with the municipal buses.

The private railways, enterprise at its boldest and most aggressive, were getting into the bus business. They still are in it, most profitably. They were also in the department-store business and the real-estate business. In both of these they were anticipated by the Hankyū Railway in Osaka, which was the first company to open a terminal department store. In one Tokyo instance, the real-estate business came first, the railway afterward. A land company that owned huge tracts in the southwestern suburbs and on into Kanagawa Prefecture built a railway, the Tōyoko, to push development and, incidentally, to make Shibuya the thriving center it is today. The Tōyoko also developed a garden city, a “city in the fields,” which is today one of the most affluent parts of Tokyo. It gave Keiō that new campus, out in Kanagawa Prefecture beyond the Tama River.

Download

Tokyo from Edo to Showa 1867-1989 by Edward Seidensticker.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Crystal Cove by Lisa Kleypas(37428)

Spell It Out by David Crystal(35361)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11272)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(6971)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5898)

The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion(5202)

A Year in the Merde by Stephen Clarke(4669)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(4630)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4227)

China Rich Girlfriend by Kwan Kevin(3905)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3857)

Beach Read by Emily Henry(3834)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3823)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(3794)

A Game of Thrones 1 by George R R Martin(3673)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3448)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(3437)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(3347)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3324)