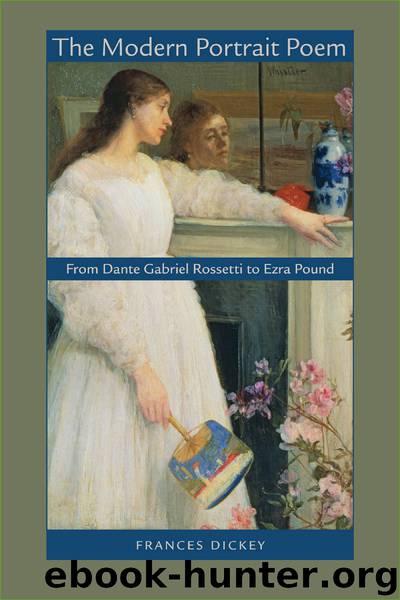

The Modern Portrait Poem by Dickey Frances;

Author:Dickey, Frances;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Virginia Press

Published: 2012-03-17T04:00:00+00:00

The previous examples from H.D., Lowell, and Pound show a process of contraction at work in a variety of tones ranging from nostalgic to satirical and biting. In all these tones, the shift from sonnet to epigram as the model for portraiture seems linked with a sense that the human subject itself has shrunk. This reduction of scale and content extended beyond the Imagist movement. In 1915, Harriet Monroe accepted two short portrait poems from Eliot that share a number of traits with those already discussed in this chapter: “Aunt Helen” and “Cousin Nancy.” The slightly longer “Mr. Apollinax” was also written at this time. In length, “Aunt Helen” and “Cousin Nancy” are each 13 lines, falling symbolically short of the sonnet by one line; “Cousin Nancy” alludes to George Meredith’s sonnet “Lucifer in Starlight” to emphasize this formal frame of reference. Both works subversively mock the conventions and proprieties of the older generation, represented by Miss Helen Slingsby in “Aunt Helen” and the aunts in “Cousin Nancy.” Whereas in “Portrait of a Lady,” the figure of the older woman threatens the young male speaker’s sense of himself, here she poses no threat and is only the object of humor. Indeed, the two poems effectively announce the changing of the guard from the Victorian era, overseen by “Matthew and Waldo / The army of unalterable law,” to the modern era, characterized by smoking, dancing women, and the footman holding the housemaid on his knees. The shortness of the two portraits signals the fate of the older generation—and the Victorian muse figure first evoked in “On a Portrait”—reduced and brought to an end.

“Aunt Helen” is a true miniature in that it retains in shrunken form many of the traits of the nineteenth-century portrait poem, including Eliot’s own “On a Portrait.” The poem is epitaphic in the sense that it is occasioned by death. In keeping with the conventions for such portraits from Cowper to Rossetti, “Aunt Helen” assesses the subject’s soul, but unlike these earlier models, finds only “silence in heaven / And silence at her end of the street.”70 The previously immortal soul is now imagined simply as a silence, an “end.” This discovery corresponds with Robinson’s and Pound’s findings of human diminishment in their own reduced portraits. In place of the soul, the poem enumerates the material accessories of life: her “small house near a fashionable square,” her cul-de-sac, her servants, her pets, and the Dresden clock on the mantelpiece. The Dresden clock is a nice touch that contrasts the durability of Aunt Helen’s possessions with her own transience. The statues of Waldo and Matthew serve a similar function in “Cousin Nancy,” standing as relics of a past era. The one possession that expires with Aunt Helen is her parrot, which “died too.” The appearance and death of the parrot mark the final migration of this potent symbol from Manet’s Young Lady in 1866 to Eliot’s “On a Portrait” to the crying parrot of “Portrait of a Lady.” In

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Still Me by Jojo Moyes(11278)

On the Yard (New York Review Books Classics) by Braly Malcolm(5528)

A Year in the Merde by Stephen Clarke(5441)

Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman(5288)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3857)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3273)

Surprise Me by Kinsella Sophie(3116)

Pharaoh by Wilbur Smith(2994)

Why I Write by George Orwell(2958)

A Column of Fire by Ken Follett(2616)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2590)

The Beach by Alex Garland(2565)

The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin(2564)

Aubrey–Maturin 02 - [1803-04] - Post Captain by Patrick O'Brian(2309)

Heartless by Mary Balogh(2263)

Elizabeth by Philippa Jones(2208)

Hitler by Ian Kershaw(2205)

Life of Elizabeth I by Alison Weir(2091)

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child by J. K. Rowling & John Tiffany & Jack Thorne(2068)