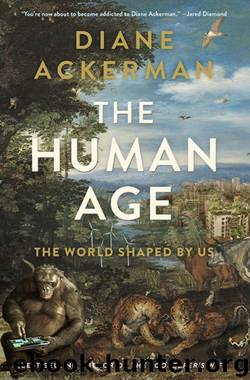

The Human Age: The World Shaped By Us by Diane Ackerman

Author:Diane Ackerman

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2014-09-10T04:00:00+00:00

WEIGHING IN THE NANOSCALE

We’re not just seeing invisibles; we’re engineering things on a minute, invisible-to-the-eye scale. “Nano,” which means “dwarf” in Greek, applies to things one-billionth of a meter long. In nature that’s the size of sea spray and smoke. An ant is about 1 million nanoparticles long. A strand of hair is 80,000 to 100,000 nanometers wide, roomy enough to hold 100,000 perfectly machined carbon nanotubes (which are 50 to 100 times stronger than steel at one-sixth the weight). A human fingernail grows about 1 nanometer a second. About 500,000 nanometers would fit in the period at the end of this sentence, with room left over for a rave of microbes and a dictator’s heart.

I’m stirred by the cathedral-like architecture of the nanoscale, which I love to ogle in photographs taken through scanning electron microscopes. One year in college, I spent off-duty hours hooking long-stranded wool rugs after the patterns of the amino acid leucine (seen by polarized light), an infant’s brain cells, a single neuron, and other objects revealed by such microdelving. How beautifully some amino acids shine when lit by polarized light: pastel crystals of pyramidal calm, tiny tents along life’s midway. Arranged on a slide or flattened on a page, they glow gemlike but arid. We cannot see their vitality, how they collide and collude as they build behavior. But their nanoscale physiques are eye-openers, and more and more we’re turning to nature for inspiration.

We used to think that wall-climbing geckos must have suckers on the soles of their feet. But in 2002, biologists at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Orgeon, and the University of California at Berkeley released their strange findings, and science was agog. Viewed at the nano level, a gecko’s five-toed feet are covered in a series of ridges, the ridges are tufted with billions of tiny tubular elastic hairs, and the hairs bear even tinier spatula-shaped boots. The natural force between atoms and molecules is enough to stick the spatulas to the surface of most anything. And the toes are self-cleaning. As a gecko relaxes a toe and begins to step, the dirt slides off and the gecko steps out of it. No grooming required.

When I learned of gecko feet from a biologist friend with an infectious sense of wonder, the idea of sticky instantly changed from a gluey sensation to a triumph of nature’s engineering. The next time I spied a gecko climbing up a stucco wall, my brain saw the tidy toes rising, and the spatula-tipped hairs clinging, even though my raw eyes couldn’t see beyond the harlequin slither. Inspired by gecko toes, scientists have invented chemical-free dry bio-adhesives and -bandages, and all sorts of biodegradable glues and geckolike coatings for home, office, military, and sports.

The nanotechnology world is a wonderland of surfaces unimaginably small, full of weird properties, and invisible to the naked eye, where we’re nonetheless reinventing industry and manufacturing in giddy new ways. Nano can be simply, affordably lifesaving during natural disasters. The 2012 spate of

Download

The Human Age: The World Shaped By Us by Diane Ackerman.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(4731)

The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate by Kaplan Robert D(3596)

Zero Waste Home by Bea Johnson(3286)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(2944)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(2942)

Good by S. Walden(2910)

The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (The Princeton History of the Ancient World) by Kyle Harper(2431)

Camino Island by John Grisham(2380)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2358)

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotter(2304)

Human Dynamics Research in Smart and Connected Communities by Shih-Lung Shaw & Daniel Sui(2175)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2105)

Energy Myths and Realities by Vaclav Smil(2054)

The Traveler's Gift by Andy Andrews(2008)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(1937)

Birds of New Guinea by Pratt Thane K.; Beehler Bruce M.; Anderton John C(1905)

Ultimate Navigation Manual by Lyle Brotherton(1764)

A History of Warfare by John Keegan(1712)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(1612)