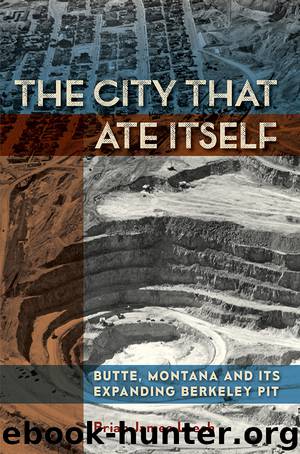

The City That Ate Itself by Brian James Leech

Author:Brian James Leech [Неизв.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780874175981

Publisher: Chicago Distribution Center (CDC Presses)

CHAPTER 6

ACQUISITION

BUTTE RESIDENTS REFLECTING on the expanding Berkeley Pit agreed on one topic: relocation hurts. Some, like Vincent Ciabattari, believed that protest against relocation was a necessary tactic, but that people, sadly, had abandoned it. In a 1974 interview, he related that his once close-knit group of neighbors had deserted him among the waste dumps. As he put it, “People said they’d fight, but then they jumped.”1 Others, like long-haul truck driver Bill Long, found the relocation process depressing but necessary. Just a few years after Ciabattari’s interview, Long pulled up next to the site where the Anaconda Company dump man directed him to release a load of waste from the Berkeley Pit. As he looked in his rearview mirror, he saw rocks tumbling out of his truck and down onto Holy Savior School, a grade school for the Catholic residents of two Butte neighborhoods: Meaderville and McQueen. The residents were now gone—the company had relocated them. The parish buildings were all that remained. Covering up the still-standing school, he later wrote, “left an indelible mark in my memory. I felt like a murderer. Progress does have its price.”2

In exploring the process of neighborhood relocation, this chapter will attempt to explain why people like Ciabattari and Long found pit expansion demoralizing but also increasingly inevitable. The decision to shift Butte’s mining to open pit was driven by the need for efficiency, with increased safety a pleasant benefit; the pit’s continued development initiated a process only partly foreseen by early planners, however. The relocation of homes, businesses, and, eventually, whole neighborhoods, soon became a necessity for the Anaconda Company and an accepted program by locals. Given residents’ early protests against open-pit mining, it seems surprising at first that a large-scale relocation program could become normalized.

Bill Long’s above comment about the price of progress suggests an initial answer to this conundrum. Access to good jobs for Butte’s residents increasingly overcame locals’ earlier resistance to open-pit mining. Worried about Butte’s smaller role in the company’s copper empire, Anaconda’s workers as well as other residents came to believe that open-pit mining’s productivity represented necessary technological progress. Journalists commented on residents’ love-hate relationship with Anaconda; as much as they resented being pushed around by it, “the people of Butte feel they owe the company everything,” as one paper put it.3 Anaconda had created Butte and it still employed almost one-third of the city’s workforce. Its workers had much pride in the industry—they had produced metals that had been significant in two world wars and in the Cold War.4 As horrible as Bill Long felt about relocation, he still believed that pit expansion equaled a healthy economy.5 One reporter described the situation rather poetically: “The Pit’s neighbors generally appear resigned to live with it. The Pit contains Butte’s life blood—copper. The Pit is life in Butte.”6 Another journalist was more blunt: “Rebellion has been dissipated by the economics of a one-industry town.”7

Employment concerns and pride in the industry might be the most obvious answers, but they are not the only ones.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Alternative & Renewable | Drilling Procedures |

| Electric | Fossil Fuels |

| Mining | Nuclear |

| Power Systems |

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton(40299)

Introduction to Aircraft Design (Cambridge Aerospace Series) by John P. Fielding(32331)

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32136)

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(17439)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(7032)

The Complete Stick Figure Physics Tutorials by Allen Sarah(6631)

Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review by Kaplan(6044)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(5778)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5761)

Learning SQL by Alan Beaulieu(5399)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5031)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(4728)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(4694)

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport;(4511)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(4493)

Audition by Ryu Murakami(4091)

1,001 ASVAB Practice Questions For Dummies by Powers Rod(4034)

Electronic Devices & Circuits by Jacob Millman & Christos C. Halkias(4021)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(3996)