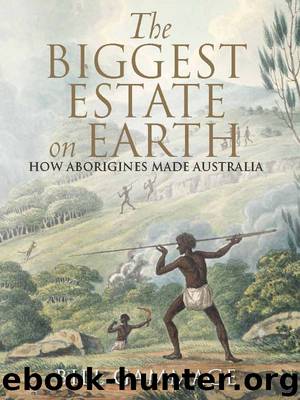

The Biggest Estate on Earth by Bill Gammage

Author:Bill Gammage

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: HIS004000, book

ISBN: 9781742693521

Publisher: Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd

Published: 2011-09-30T16:00:00+00:00

9

A capital tour

Until 1788 almost no-one in Australia imagined attack from the sea. Sea and shore belonged to the Dreaming, eternal eddies. Only in Sydney and Adelaide did any invader attempt to understand this or any aspect of 1788 life, but the land that newcomers took tells much about the people who made it, while fire and no fire patterned country in ways which influenced where newcomers settled. In this way, sometimes slightly, sometimes clearly, the people of 1788 shaped the layout of Australia’s capital cities.

Capital sites had two primary needs: a port, and fresh water. It was an elusive combination. The need for water pushed all but Darwin onto streams slightly inland, like the great British ports. All these streams were shallow, some of them mere chains of ponds. They served not because their supply was good, but because it was worse elsewhere. This obliged all but Perth to reject earlier sites, and Brisbane, Perth, Adelaide and Melbourne to separate port and capital. Even so, every capital was soon pressed by want of water, and still is. All had swamps, springs, soaks and wetlands, but by ‘fresh’ newcomers meant ‘running’, for them and for their mills, tanneries, breweries and other improving enterprises. Few liked swamps, many despised them, none knew how to care for them. What people until 1788 prized most, the newcomers prized least. Sometimes deliberately, sometimes not, as soon as they landed they began to destroy.

Sydney, 26 January 1788

Below the Archibald Fountain in Hyde Park a spring percolated through sandstone into a small marsh, then trickled west and north down a gully to a cove west of Bridge and Pitt streets. In flood it sprayed mud flats there, but usually it had only a small flow, and in drought it dried up. Newcomers called it the Tank Stream, because they cut a water tank in it. Fresh water was precious in this porous sandstone, and until 1788 people sheltered the creek with tiers of foliage, many with edible leaves, berries or fruit. Banksias and acacias below giant Scribbly Gum, Red Bloodwood or Sydney Red Gum gave an outer shield. Inside, orchids, lilies, herbs and a ‘fairy dell of wild flowers and ferns’ flourished beneath Cabbage and other palms and a damp-loving scrub of melaleuca, kunzea and leptospermum. Fire welcoming and fire sensitive plants grew together. Few fires came, but perhaps every 4–5 years careful cool burns, probably in winter, kept these unlikely companions side by side.

About 350 metres from the cove, just where it was easiest to maintain such lush vegetation, it gave way to a gum grove and a camp. Newcomers recorded the cove’s name as Warrang, from ngurrung, camp, and found scatters of stone tools and chips at Angel Place, off Pitt Street.1 ‘Along shore was all bushes’, Jacob Nagle wrote, ‘but a small distance at the head of the cove was level, and large trees but scattering, and no under wood worth mentioning, and a run of fresh water.’ The grove was burnt more

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Historic | Information Systems |

| Regional |

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6002)

The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate by Kaplan Robert D(4066)

Zero Waste Home by Bea Johnson(3831)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3617)

Good by S. Walden(3547)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3535)

The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (The Princeton History of the Ancient World) by Kyle Harper(3055)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2855)

Camino Island by John Grisham(2793)

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotter(2684)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2678)

Human Dynamics Research in Smart and Connected Communities by Shih-Lung Shaw & Daniel Sui(2499)

Energy Myths and Realities by Vaclav Smil(2483)

The Traveler's Gift by Andy Andrews(2454)

9781803241661-PYTHON FOR ARCGIS PRO by Unknown(2365)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(2349)

Birds of New Guinea by Pratt Thane K.; Beehler Bruce M.; Anderton John C(2249)

A History of Warfare by John Keegan(2238)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2197)