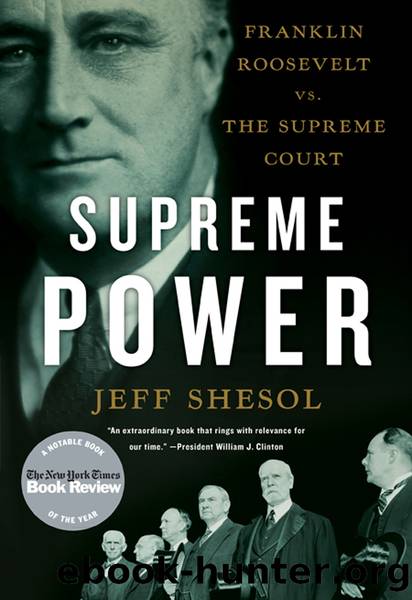

Supreme Power by Jeff Shesol

Author:Jeff Shesol [Shesol, Jeff]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Published: 2010-05-14T16:00:00+00:00

Still, he was confidentâand not without cause. âAll odds [are] that the President [will] get what he wanted,â Time predicted in mid-February, and it was hard to find anyone in Washington who disagreed. White House advisers, cabinet members, House and Senate leaders and back-benchers, Capitol Hill reportersâall took it for granted that Roosevelt would prevail. It might take longer than initially expected, he might have to work harder than planned, but the outcome seemed assured. âThe President has, of course, the better of the situation,â grumbled Hiram Johnson, who wrote his son that âthe chances are ten to oneâ in FDRâs favor.

Liberal support appeared to coalesce. âIt is becoming clearer,â The Nation reported, âthat the labor, farmer, and progressive sentiment of the country is supporting the proposal.â It seemed to be the one thing that various labor factions could agree on. The leadership of the AF of L (after considerable argument) formally endorsed the Court bill on February 17, while the Labor Non-Partisan League, created in 1936 to campaign for FDR, sent letters to every member of Congress expressing the groupâs expectation that every friend of labor would get behind the plan. (âI am sure we will be asked for the quid pro quo for this support,â wrote James Roosevelt in his diary.) And farm groups, with the notable exception of the National Grange, began to line up behind the billâpartly at the incitement of Henry Wallace, who told a conference of farm leaders that if the Court plan passed, the administration would be able to revive the AAA in a slightly modified form. Indeed, the White House took this opportunity to suggest that it might reconstitute much of the original New Deal, including parts of the NRAâthe parts that labor unions liked.

âRoosevelt Will Win,â declared The Nation, adding that soon, the shouting would die down, the bill would pass, and âthere will be nothing left to do but see which of the justices decides to be lead-off man on the retirement list.â The press was already speculating about the identity of Rooseveltâs eventual appointees. Robinson, Ashurst, Sumners, Richberg, and Frankfurter led most lists; also mentioned were Corcoran, Cohen, Rosenman, and Robert Jackson, as well as Senators Black, Byrnes, Harrison, Minton, and Wagner. Friends of Roosevelt began lobbying him on behalf of their own preferred picks. âI respectfully recommend to you Mr. Owen D. Young,â wrote Thomas Watson of IBM. Young, he noted, was chairman of the board at General Electric and possessed âa very deep appreciation of the changing conditions in our country.â

This was all a bit premature. A Gallup poll taken during the week of February 15 showed an even split in public opinion: 45 percent in favor, 45 percent against, with 10 percent undecided. A week later, opponents had gained a slight advantage. Roosevelt had work to do in building public support. Still, these mixed results could be seen as good news. Even though he had not yet begun to fightâhe had not uttered a word publicly in defense of his plan since the day of its unveilingâroughly half the nation was behind him.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1184)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1162)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1136)

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1112)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1033)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1019)

Tip Top by Bill James(1004)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1003)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1001)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1000)

F*cking History by The Captain(969)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(943)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(908)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(903)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(881)

American Dreams by Unknown(860)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(850)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(817)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(813)