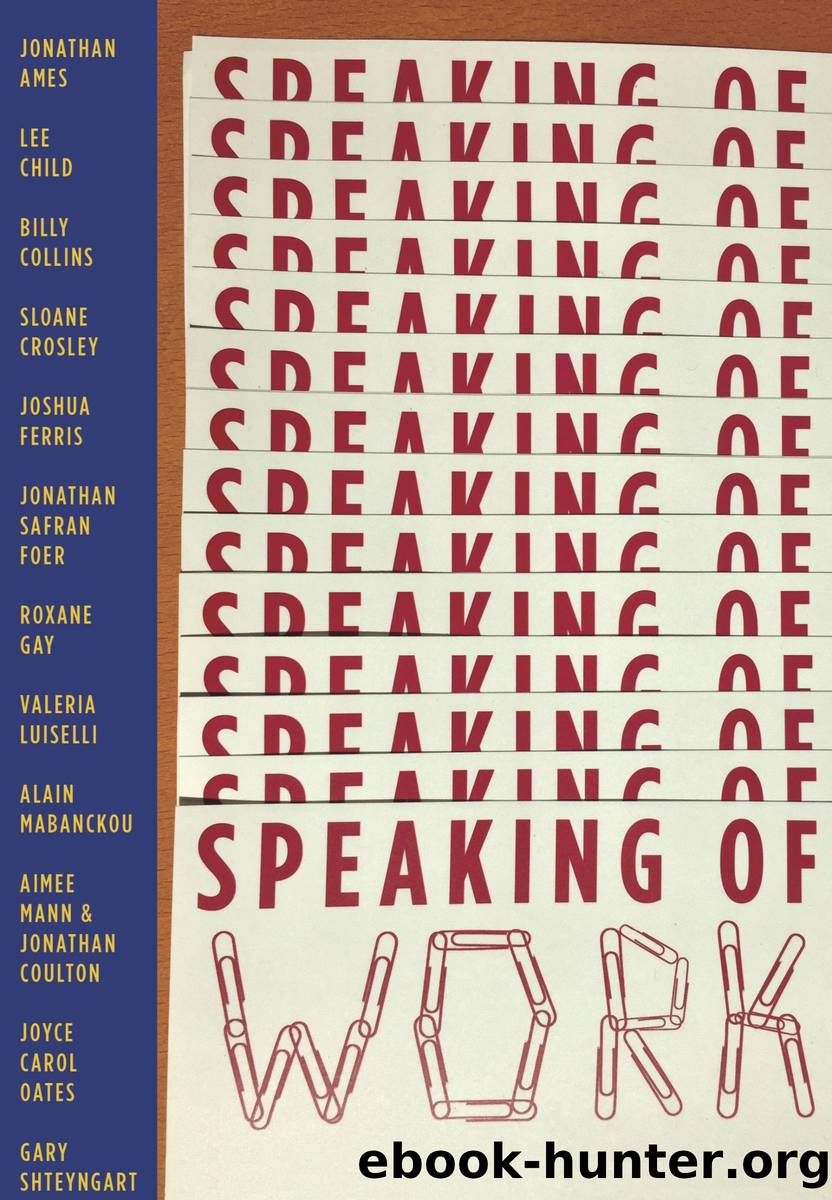

Speaking of Work by Bernard Schwartz

Author:Bernard Schwartz

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Absurdist fiction, Dark humor, Feminist lit, Hispanic woman, Humor memoir, Memoir 1980s, Office drama, Poetry at work, Suspense story, World literature

Publisher: Bernard Schwartz

Published: 2017-10-17T00:00:00+00:00

I donât know how long the months after my divorce lasted. Months is a guess. One night I didnât wake up until morning, and after that I never watched another documentary.

Have you ever come across the word âesquivalience?â Itâs a made-up wordâa âghost wordââin the New Oxford American Dictionary, created to detect breaches of copyright. (There would be no other way to know if another dictionary-maker had simply stolen Oxfordâs list of words; ghost words prove plagiarism.) For the same reason, encyclopedias of music often include a piece of nonexistent music, and mathematic tables often contain nonexistent equations, and, hauntingly, most atlases map at least one fictitious place. Theyâre known as âpaper towns,â or âphantom settlementsâ.

There was a phantom settlement in upstate New York (in old Esso maps) called Agloe. But it lost its phantom status in the 1950s when someone, believing himself to be in Agloe, opened the Agloe General Store there, and it became a real place. The store closed, but the place persisted. It was included in other atlases, and continued to exist until the 1990s, at which point it disappeared again. But it didnât disappear to the same non-existence. Itâs more like a personâthe death after life is different than the death before being born.

Esquivalience is defined as âthe willful avoidance of oneâs official responsibilities.â

Itâs nice to imagine being esquivalientâmaybe even living in oneâs own phantom settlement, speaking only ghost words over nonexistent musicâwhile at the same time utterly responsible and devoted to all of the things one loves. That would be something.

One day Iâll tell you the fullest version of this story, which ended up changing my life in some dramatic and concrete ways, but this will do for now: about two years ago, I went to Chicagoâwhere Iâm fromâto visit the dying mother of my oldest friend. She used to carry me down the stairs of nursery school when Iâd become panicked at the top. (Humans arenât born with a fear of heights, by the way, they learn it.) Thirty years later, I was panicked about going to see herâbeing at the top of deathâs stairsâbut it was my turn to carry her. It wasnât the proximity to death that I was afraid of, but that I might accidentally say too much, or too little. To protect against awkward silences, I brought a small stack of poems to read. That afternoon was one of the least awkward of my life, but I did end up reading her the poems, and rereading them.

At the bottom of this e-mail is one of the poems I read to her. Itâs by the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky. That lineââI wish I knew no astronomy when stars appearââis one way to summarize all that weâve exchanged thus far.

Brodsky was put on trial when he was 24, and ultimately sent to a labor camp in Siberia. His case turned him into a symbol of artistic resistance, and a hero to poets everywhere. (He won the Nobel Prize in 1987.) Here are just a few lines from the transcript:

JUDGE: What is your specific occupation?

BRODSKY: Poet.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32536)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31933)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31925)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7485)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5751)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(5604)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4924)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(4385)

Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade by Robert Cialdini(4208)

I Have Something to Say: Mastering the Art of Public Speaking in an Age of Disconnection by John Bowe(3871)

Elements of Style 2017 by Richard De A'Morelli(3336)

The Book of Human Emotions by Tiffany Watt Smith(3287)

Fluent Forever: How to Learn Any Language Fast and Never Forget It by Gabriel Wyner(3071)

Name Book, The: Over 10,000 Names--Their Meanings, Origins, and Spiritual Significance by Astoria Dorothy(2967)

Why I Write by George Orwell(2944)

Good Humor, Bad Taste: A Sociology of the Joke by Kuipers Giselinde(2939)

The Art Of Deception by Kevin Mitnick(2784)

The Grammaring Guide to English Grammar with Exercises by Péter Simon(2733)

Ancient Worlds by Michael Scott(2672)