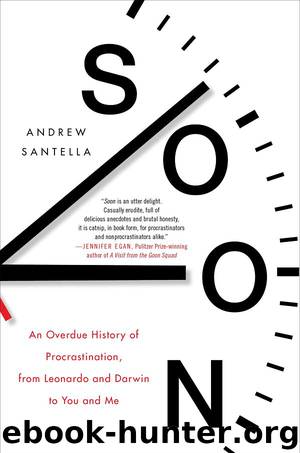

Soon by Andrew Santella

Author:Andrew Santella

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins

Published: 2018-03-13T04:00:00+00:00

6

Seeds

Cras melior est.

—Motto of the Lichtenbergian Society

In the last decades of the eighteenth century, strollers on the streets of Göttingen in Lower Saxony became accustomed to seeing a man on the top floor of a half-timbered house on the Gotmarstrasse peering down at them as they walked. This was Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, one of the intellectual superstars of Enlightenment Europe.

A sensationally popular lecturer and showman of the sciences at the University of Göttingen in the 1760s, Lichtenberg was an eighteenth-century version of today’s globetrotting academic luminaries: member of an intellectual circle that included Goethe, Kant, and Alessandro Volta; stager of science demonstrations that drew students and admirers from around Europe; chummy conversational partner to the king of England. If there had been TED Talks in the Enlightenment, Lichtenberg probably would have been pacing the stage in a periwig and wireless headset.

Lichtenberg was tiny and humpbacked and also something of a rock star. His lectures were routinely packed with visitors who had traveled to Göttingen to see him. He was hired at the university not only for his scientific abilities, but also because the administration hoped that his charisma, reputation, and showmanship would attract other scholars.

His life seemed to overflow with ideas and enthusiasms. That overflow could be problematic. Lichtenberg never seemed able to focus his energies. Or was it that Lichtenberg wasn’t interested in focusing? Again and again, Lichtenberg did work that laid a foundation for new breakthroughs, only to leave the breaking through to others. Lichtenberg demonstrated the scientific basis for hot-air balloon flight years before the Montgolfier brothers were able to achieve the first actual balloon flight. He himself never tried to leave the ground.

Lichtenberg spoke often of writing a novel in the style of Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones. But there never seemed to be time. There were always lectures to give, letters to write, strolls to take. At his death, at fifty-six, Lichtenberg had finished only a few pages of his novel.

He dabbled. The wide scope of Lichtenberg’s intellectual curiosity was part of his appeal, part of his genius. He lectured on astronomy and mathematics and geodesy and volcanology and meteorology and experimental physics. He authored an extended art-critical analysis of the prints of the English artist William Hogarth. He wrote short essays about what we would call psychology. Lichtenberg was sometimes frustrated by his own dabbling, by his failure to stick to the task at hand. The regret is unmistakable in one of his diary entries: “I had Montgolfier’s invention within my reach,” he wrote with the dismay of one smacking himself on the forehead.

Even in his achievements, you find traces of Lichtenberg’s procrastination. One of his great discoveries in electrostatics came as a result of stepping away from his work one day to tidy up the scientific equipment in his laboratory—just the kind of task-avoidance any procrastinator would recognize. He had built an electrophorus, a metal disk about six feet in diameter, a device popularized by his friend Volta and used to generate an electrostatic charge.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5780)

Paper Towns by Green John(5195)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4948)

The Doodle Revolution by Sunni Brown(4772)

Hyperfocus by Chris Bailey(4126)

Evolve Your Brain by Joe Dispenza(3681)

Unlabel: Selling You Without Selling Out by Marc Ecko(3668)

The Red Files by Lee Winter(3418)

Draw Your Day by Samantha Dion Baker(3369)

The Power of Mindful Learning by Ellen J. Langer(3226)

The Art of Dramatic Writing: Its Basis in the Creative Interpretation of Human Motives by Egri Lajos(3072)

The War Of Art by Steven Pressfield(2964)

Applied Empathy by Michael Ventura(2908)

The 46 Rules of Genius: An Innovator's Guide to Creativity (Voices That Matter) by Marty Neumeier(2859)

How to be More Interesting by Edward De Bono(2797)

Keep Going by Austin Kleon(2768)

Why I Am Not a Feminist by Jessa Crispin(2764)

How to Stop Worrying and Start Living by Dale Carnegie(2729)

You Are Not So Smart by David McRaney(2660)