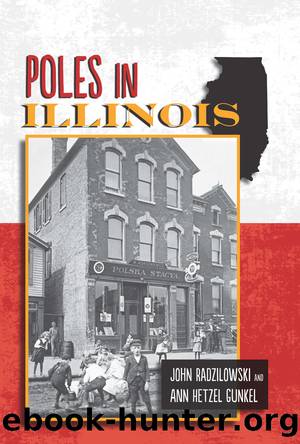

Poles in Illinois by Radzilowski John; Gunkel Ann Hetzel;

Author:Radzilowski, John; Gunkel, Ann Hetzel; [Неизв.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Southern Illinois University Press

Business and Professionals

Poles in Illinois were overwhelmingly industrial workers, but the size and complexity of the Polish community allowed for the development of Polish-run businesses and a small professional class as well. A proportion of trade in Polish neighborhoods was run by Jewish merchants, mainly those with origins in Poland and Eastern Europe, reproducing a pattern of ethnic relations that was familiar yet often fraught with mutual tension. Polish Jews arriving in America likely had more commercial experience than their gentile neighbors, and they were often able to take advantage of established networks of Jewish merchants who helped their compatriots (often relatives or people from the same hometown) get started in business. Jewish merchants often spoke the languages of their gentile neighbors and were more likely to extend credit to them than were most American stores. During periods of strife, there were sometimes calls to boycott Jewish stores in Polish neighborhoods. This was most notable during the long, hot summer of 1919, when tensions over the role of Jews in newly independent Poland riled both communities, leading to a battle in the pages of Polish and Jewish newspapers in Chicago that featured heated accusations of treachery, anti-Semitism, and charges of un-American activity.41 Polish newspapers called for boycotts of Jewish businesses, while Jewish newspapers portrayed Chicagoâs Poles as a menace to Jewish life and property. The rhetoric was not acted upon, however, as Poles continued to shop in Jewish stores and Jews continued to open their stores to Polish customers.

While Poles were slower to open businesses than their Italian or Jewish counterparts, Chicago developed a sizeable Polish business community by 1900 (see figure 5.1). The most common sort of business to enter was saloonkeeping. Startup costs were moderate, and with the proper connections, a liquor license could be had for five hundred dollars. The demand was high, since saloons served as clubs for the cityâs large population of unattached, male factory workers. In addition to alcohol, saloons provided cheap food and camaraderie. Some saloons even kept a supply of newspapers and reading material. They were places for political organizing, and they even served as voting stations at times. Saloonkeepers were viewed with ambivalence in Polonia. They were sometimes denounced for exploiting workers, especially given Poloniaâs serious problems with drunkenness. Other saloonkeepers were viewed in a more favorable light, and some parleyed their businesses into larger enterprises or political careers. Aside from saloons, Poles also opened many restaurants, bakeries, and small grocery, butcher, and tobacco shops. Since women and children were generally not allowed in saloons, ice cream and soft drink parlors provided places where families could go on special occasions to indulge their sweet tooth.

Professionals, such as doctors, lawyers, and dentists, were a consistent and well-established presence in Chicagoâs Polish business community. Many of them doubled as leaders of important community organizations and fraternal associations. Another important group of businesses included community banks and savings and loan associations. The latter were popular among immigrants for obtaining mortgages. By 1930, one Chicago directory listed 17 Polish community banks and 120 savings and loan associations.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1707)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1625)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1553)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1455)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1430)

Tip Top by Bill James(1416)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1376)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1359)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1354)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1336)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1315)

F*cking History by The Captain(1304)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1300)

American Dreams by Unknown(1286)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1274)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1257)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1212)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1174)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1126)