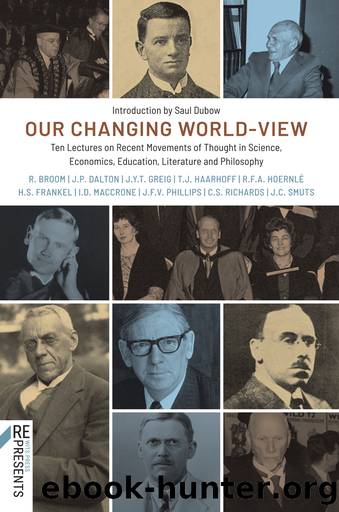

Our Changing World-View by unknow

Author:unknow

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, Historiography

ISBN: 9781776145553

Google: 6QM7EAAAQBAJ

Publisher: NYU Press

Published: 2021-08-15T01:05:28+00:00

Literature in the Machine Age

By

J. Y. T. GREIG

M.A., D.Litt.

Professor of English

Literature in the Machine Age

When we look back over the course of English literature from about the year 1800 until the present time, and compare the work of the major writers with that of major writers in any earlier period, two facts emerge. The first is this: nearly all the major writers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and many of the minor writers too, are ill at ease. They are not all ill at ease about the same things, and many of them are quite unable to define the causes of their discontent; but they are alike in having no firm foothold, no assured place, within the society of their own time. And the second fact is this: as the nineteenth century passes into the twentieth, literary discontent seems to increase rather than diminish, the gulf between writers and society, instead of being bridged, widens.

Some of the earlier writers of the periodâthose we are wont to call the Romanticsâallay their uneasiness by taking refuge in some fairyland of the fancy that bears very little relation to the life of every day, or in some remote period of time the life of which appears more congenial to their troubled spirits. Coleridge flees to Xanadu or achieves a dream-like serenity with his Ancient Marinerâ

Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide, wide sea;

or, driven back to Highgate, escapes once more into the fog of German metaphysics. Byron is for ever stridently running away; Childe Haroldâs Pilgrimage may not lead to anywhere in particular, but it leads very definitely away from what was troubling Byron, namely, himself, and the men and women of his time. Keats the Cockney, had he lived longer, might have achieved an almost perfect synthesis of the Greek spirit and the spirit of the English Elizabethans; but never, so far as we can tell, would he have proved the poet of his own age. Shelley has no abiding place on earth, no home except amid the clouds. Scott, less sensitive perhaps than any of the others, a man whom we might have expected to find tolerably at ease in the Zion of early nineteenth-century Edinburgh, is none the less driven to seek a spiritual refuge in the Middle Ages and in the eighteenth-century Scotland that had virtually passed away before he grew to manhood; what was Scottâs so-called Toryism but a continual protest against the political, social and economic tendencies of his day? Wordsworth, after an initial period of revolutionary fervour, renounces the world of affairs, to enter into a mystical, satisfying, but somewhat ill-defined communion with Nature. Charles Lamb is an Elizabethan, Hazlitt a malcontent in most things, Leigh Hunt a malcontent in politics and at the same time a somewhat sugary regressionist in literature.

So again later in the century. Tennyson, that mellifluous technician and delayed adolescent, is obviously perplexed and puzzled by contemporary life: he flees in the flesh to a hedge-concealed fastness in the Isle

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

International Integration of the Brazilian Economy by Elias C. Grivoyannis(111059)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12028)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8050)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7707)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7129)

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert T. Kiyosaki(6633)

Pioneering Portfolio Management by David F. Swensen(6301)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6019)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5802)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4753)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4478)

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff(4293)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4250)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(4207)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4191)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4007)

The Dhandho Investor by Mohnish Pabrai(3765)

The Wisdom of Finance by Mihir Desai(3748)

Blockchain Basics by Daniel Drescher(3583)