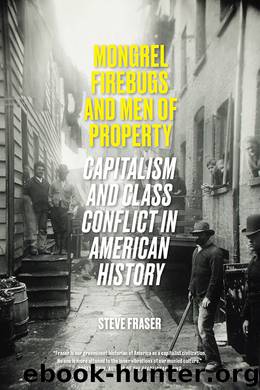

Mongrel Firebugs and Men of Property by Steve Fraser;

Author:Steve Fraser;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Penguin Random House LLC (Publisher Services)

Following the bloody debacle at Homestead, which helped reelect the Democrat Cleveland in 1892, Andrew Carnegie, a nominal Republican, confided his true feelings about the outcome to Henry Clay Frick: “Cleveland! Landslide! Well, we have nothing to fear and perhaps it is best. People will now think the Protected Manufacturers are attended to and quit agitating. Cleveland is a pretty good fellow. Off for Venice tomorrow.” As Henry Adams noted, “The amazing thing is that no one talks about real interests. By common consent they agree to let these alone. We are afraid to discuss them.” After all, as William McKinley, campaigning in 1896 from his front porch in Ohio, explained, “In America we spurn all class distinctions. We are all equal citizens and equal in privilege and opportunity.”

In our own time, that refrain still reverberates. Indeed, for the past quarter-century, it might be taken as an understatement. Our political vocabulary has been wiped clean of all references to the class struggle, except insofar as they may be used to stigmatize any such allusions as heinously alien to the American way. On the one hand, the age of Reagan was marked by inequalities in income and wealth that exceeded those of the first Gilded Age. Crony capitalism and subordination of the state to private interests have been at least as naked and, if anything, more systematically organized than what was decried as the “Great Barbecue” of post–Civil War politics. The piggish display of wealth characteristic of the “gay nineties” has nothing on the hedge-fund hog heaven of our own day. Yet if America during the first Gilded Age might be thought of as society living on the edge, its ruling class and ruling beliefs subject to chronic resistance and Jehovian denunciation, the country passed through its second Gilded Age in a state of acquiescent torpor. The more things stay the same, the more they change.

Even as the curtain descends on the second Gilded Age, even as we enter a new era that seems bound to open up political possibilities not dreamed of for a long generation, the mystery remains: How is it that such similar moments in the national saga could elicit such starkly different reactions? Solving this mystery may even have some bearing on what lies ahead. Two books that examine, in turn, the underlying economic transformations and the politics of consent that defined the second Gilded Age illuminate this subject.

Bad Money, by Kevin Phillips, takes up the subject of the financialization of the US economy during what he calls the “age of Reagan” (the period from 1980 to the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the rest of the American and global financial system in the fall of 2008).1 Phillips and others have been sounding alarm bells about this development for well over a decade. Financialization, or what he sometimes aptly characterizes as financial mercantilism, is one way of describing a reordering of our economic life that is, in certain essential ways, the opposite of what happened during the first Gilded Age.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

International Integration of the Brazilian Economy by Elias C. Grivoyannis(57296)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10903)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(7033)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(6629)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(6185)

Pioneering Portfolio Management by David F. Swensen(5600)

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert T. Kiyosaki(5140)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4818)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(4731)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3774)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3566)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3456)

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff(3413)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(3278)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3259)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(3173)

The Dhandho Investor by Mohnish Pabrai(3162)

The Wisdom of Finance by Mihir Desai(3070)

Blockchain Basics by Daniel Drescher(2884)