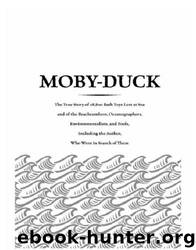

Moby-Duck

Author:Donovan Hohn

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Penguin Group USA, Inc.

Published: 2011-02-01T16:00:00+00:00

JOSHUA THE MOUSE

What is childhood? Ever since I learned I was to become a father, this question has been on my mind. Developmental psychologists like T. Berry Brazelton will tell you that infancy and toddlerhood and childhood and adolescence are neurologically determined states of mind—developmental stages through which all of us progress. Sociologists and historians, meanwhile, tell us that childhood is an idea, distinct from biological immaturity, the meaning of which changes over time. In his seminal 1962 study of the subject, the French historian Philippe Ariès argued that childhood as we know it is a modern invention, largely a by-product of schooling. In the Middle Ages, when almost no one went to school, children were treated as miniature adults. At work and at play, there was little age-based segregation. “Everything was permitted in their presence,” according to one of Ariès’s sources, even “coarse language, scabrous actions, and situations; they had heard everything and seen everything.” Power not age determined whether a person was treated as a child. Until the eighteenth century, the European idea of childhood “was bound up with the idea of dependence: the words ‘sons,’ ‘varlets,’ and ‘boys,’ were also words in the vocabulary of feudal subordination. One could leave childhood only by leaving the state of dependence, or at least the lower degrees of dependence.” Our notion of childhood as a sheltered period of innocence begins to emerge with the modern education system, Ariès argues. As the period of economic dependence lengthened among the educated classes, so too did childhood. These days education and the puerility it entails often lasts well into one’s twenties, or longer.

Twenty years after Ariès published his book, the media critic Neil Postman announced in The Disappearance of Childhood that modern childhood as Ariès described it had gone extinct, killed off by the mass media, which gave all children, educated or otherwise, premature access to the violent, sexually illicit world of adults. Children still existed, of course, but they’d become, in Postman’s word, “adultified.” I was ten years old when Postman published his book, and in many respects my biography aligns with his unflattering generational portrait. In Postman’s opinion the rising divorce rate indicated a “precipitous falling off in the commitment of adults to the nurturing of children.” My parents divorced just as the American divorce rate reached its historical peak. After my mother moved out for good, my brother and I came home from school to an empty house where we spent hours watching the sorts of television shows Postman complains about (Three’s Company, The Dukes of Hazzard). Reading Postman’s diagnosis, I begin to wonder if he’s right. Maybe my childhood went missing.

But then I think of Joshua the Mouse. One day at the school where I used to teach I stopped to admire a bulletin board decorated with construction paper mice that a class of first graders had made. Above one mouse there appeared the following caption: “My mouse’s name is Joshua. He is 20 years old. He is afraid of everything.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6011)

The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate by Kaplan Robert D(4076)

Zero Waste Home by Bea Johnson(3835)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3618)

Good by S. Walden(3549)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3537)

The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (The Princeton History of the Ancient World) by Kyle Harper(3062)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2859)

Camino Island by John Grisham(2797)

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotter(2689)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2679)

Human Dynamics Research in Smart and Connected Communities by Shih-Lung Shaw & Daniel Sui(2500)

Energy Myths and Realities by Vaclav Smil(2489)

The Traveler's Gift by Andy Andrews(2460)

9781803241661-PYTHON FOR ARCGIS PRO by Unknown(2365)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(2352)

Birds of New Guinea by Pratt Thane K.; Beehler Bruce M.; Anderton John C(2254)

A History of Warfare by John Keegan(2240)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2201)