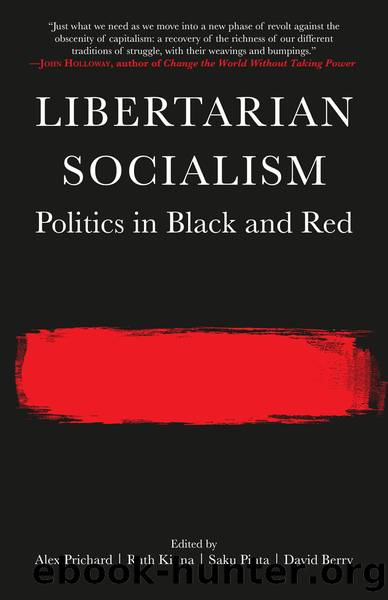

Libertarian Socialism by Prichard Alex; Kinna Ruth; Pinta Saku

Author:Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: PM Press

Published: 2017-03-15T00:00:00+00:00

Anarchists and socialists become non-violent revolutionaries

Most of the militant war resisters were released in the months surrounding the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the USA. Horrified by the scale of callous violence unleashed by the bomb, they expected a mass movement to arise in opposition to its use. In the August 1945 issue of Politics, which maintained close ties to Why? and Retort, editor Dwight MacDonald argued that the USAâs willingness to use atomic weapons meant, simply, âWe must âgetâ the modern national state, before it âgetsâ us.â12 MacDonald began his political career in the Trotskyist movement and was later considered a major figure among the âNew York Intellectualsâ. The war and the bomb, however, had pushed him into the anarchist-pacifist camp.13 Many former-COs concurred with MacDonaldâs anti-statism, as well as his assertion that to prevent another war, the entire society, structured in violence as it was, had to be transformed.

One key to such a transformation, they agreed, was continuing the fight against segregation and other manifestations of white supremacy. As early as 1942, the socialist radical pacifists Bayard Rustin, George Houser and James Farmer had launched the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to put Gandhian techniques into play to combat the segregation of restaurants, swimming pools and other public facilities. In 1947, CORE organised a Journey of Reconciliation, in which an interracial team of volunteers â including Rustin, the anarchist Igal Roodenko and Wieckâs cellmate Jim Peck â travelled by bus through southern states to test compliance with a 1946 Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation in interstate transportation facilities. Some of the riders faced beatings and were sentenced to work on the chaingang for their breach of racial protocol, but their treatment was much less severe than that encountered by participants in COREâs iconic 1961 Freedom Rides, modelled on the 1947 trip.14

After their release, former-COs such as Dellinger, DiGia and Sutherland also launched the Committee for Non-violent Revolution (CNVR). Two years later, in 1948, they regrouped with additional radical pacifists such as Muste and MacDonald, changing their name to Peacemakers.15 In the late 1940s, many radical pacifists continued to maintain membership in the Socialist Party. Differences between anarchists and socialists involved with CNVR and Peacemakers were subsumed under the mantle of an emerging politics of revolutionary non-violence. The abstract question of whether a stateless society was possible, and what it would look like, took a back seat. However, members of both groups determined that âdecentralized democratic socialism,â a version of worker self-management, was their economic ideal and agreed that direct action, rather than electoral campaigns, should be the primary means used to force a fundamental transformation of the modern war-making nation-state. Peacemakers also sought to synthesise socialist and anarchist models of organisation: the group structured itself as a network of small cells that elected a steering committee, but operated autonomously from one another in pursuit of the organisationâs defined goals. Sympathisers were encouraged to join and participate as small groups, rather than as individuals. As historian Scott

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1691)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1620)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1546)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1452)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1419)

Tip Top by Bill James(1409)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1364)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1350)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1346)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1324)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1307)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1294)

F*cking History by The Captain(1289)

American Dreams by Unknown(1277)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1254)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1249)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1207)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1167)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1115)