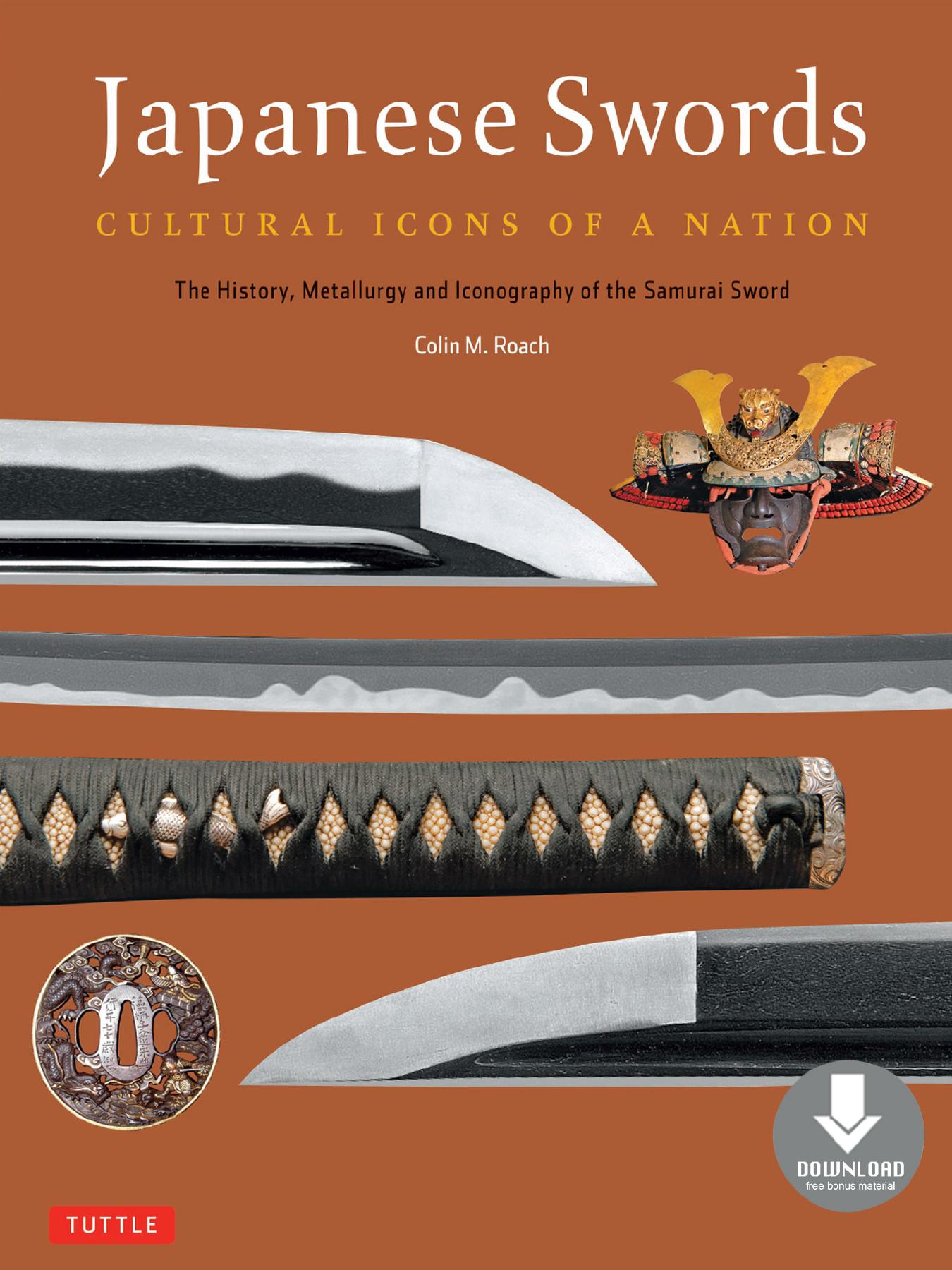

Japanese Swords by Colin M. Roach

Author:Colin M. Roach

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

ISBN: 978-4-8053-1035-9

Publisher: Tuttle Publishing

Bows and spears formed the samurai’s first lines of offense, with the sword usually being reserved for when the supply of the former had been exhausted.

The Sword of Esoteric Buddhism

During the time that the Nihōn Shōki and Kōjiki were being written, Chinese philosophies were surging into Japan. The result was a coalescence of Shinto and Buddhist theologies and practices. As Joseph Campbell writes, often the two religions “are so closely mixed one cannot tell where the Buddhism ends and the Shinto begins.”9 The symbolism of the sword as an icon thus evolved as a product of combined and adapted ideologies. As Japan’s earliest swords were imported from China, so too were many of the blade’s symbolic meanings. This evolution of the sword as a symbol acted as a vehicle for societal change. The samurai, who revered and wielded swords, knew all too well the power that they carried at their sides. Non-samurai were also aware that the sword symbolized both the power to harm and to heal. The swordsman’s hand and spirit wielded the ability to shelter the population, ward off oppressors, and suppress evil. On this level, the sword can be understood to reflect the soul of Japan itself. Just as Chinese influence made its mark on Japan, so too did the philosophy. The image of the warrior-scholar, like many other facets of Japanese culture, was adapted to suit the unique circumstances of the Japanese.

The Japanese found the mystical nature of esoteric Buddhism complimentary to previously held Shinto values and practices. Instead of abandoning Shinto beliefs in favor of Buddhist, the Japanese assimilated one into the other. The result was a distinctly Japanese version of imported beliefs, after all Buddhism was already, in its Chinese forms, inextricably intermixed with what scholars label “Taōism,” and “Confucianism.” These viewpoints, values, and practices were adapted to suit Japanese culture, and contributed heavily to the societal changes. Like the Chinese, the Japanese honored mystical aspects of the universe, but did so from a Shinto vantage point. The shared acceptance of mysticism allowed esoteric practices imported from China to snap into place like pieces of a puzzle.

It should be noted that precedence for Buddhism to adapt had been set in other cultures. In fact, as Buddhism traveled throughout Asia and took root, it evolved by adapting to the cultures it encountered along the way. King writes:

In India, it [Buddhism] had made the Hindu gods into loyal assistants and protectors of the Buddha. The general resulting pattern was that of gods as helpful in securing this-worldly blessings (health, riches, success, safety) with final (nirvanic) salvation reserved as Buddha’s exclusive potency. This pattern was followed in Japan with regard to the kami. They were to be honored and prayed to for safety, victory in battle, prosperity, and the like. Hachiman, the Shinto god of war, was constituted one of the bōdhisattvas, those almost-Buddhas dedicated to bringing humankind to salvation by their compassion and wisdom. Kami were the protectors of the Buddha, their small shrines placed in his large temples.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12006)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4901)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4765)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4672)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4476)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4191)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3987)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3946)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3936)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3539)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3321)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3181)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(3164)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3113)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(2989)

Hitler's Flying Saucers: A Guide to German Flying Discs of the Second World War by Stevens Henry(2742)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2663)

The Second World Wars by Victor Davis Hanson(2515)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2497)