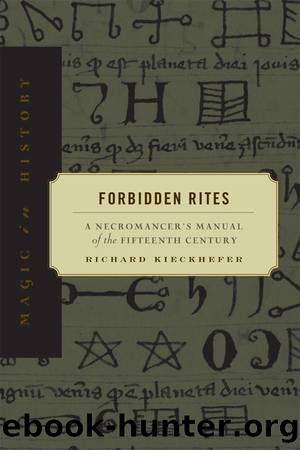

Forbidden Rites: A Necromancerâs Manual of the Fifteenth Century (Magic in History) by Richard Kieckhefer

Author:Richard Kieckhefer [Kieckhefer, Richard]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Penn State University Press

Published: 1998-03-05T05:00:00+00:00

7

Demons and Daimons:

The Spirits Conjured

In his recent study of late Byzantine demonology, Richard Greenfield distinguishes between a âstandard orthodoxâ tradition of demonology and âalternativeâ traditions. The former sees demons as immaterial, as ranked under a single chief (Satan, the Devil), and as acting only with Godâs permission or through illusion (which they use because, weakened by Christ, they must dupe humans into believing they still wield power). The latter ascribe some degree of materiality to them, classify them in various hierarchies with multiple leaders, and ascribe some power to the demons themselves.1 Greenfield says that in the alternative traditions, âit is always assumed that the demons are free to obey the practitioner or are capable of doing what he wants as long as sufficient or coercion is provided. There is no suggestion that they can only do so if allowed to by God for the ends of divine providence or economy, the state of affairs required by standard belief â indeed, many of the purposes for which they are employed would seem to be most inappropriate, if not actually contradictory to normal Christian concepts of Godâs purposes.â2 Greenfield does not mean to suggest a clear or sharp dichotomy, but rather a strong difference in tendency between the theological purists and those with alternative and at least implicitly non-orthodox views.

With perhaps some differences in nuance, one can make the same rough distinction for the later medieval West as well, and some if not all of the specific contrasts that Greenfield isolates would apply in the West. Most fundamentally, one can discern â in the Munich manuscript, as in Western magic generally â a tension between the early Christian notion of demons as fallen angels, whose status is determined by their free moral act of rebellion against God, and the Graeco-Roman conception of daimones (or daemones in Latin) as spirits linked with the world of nature, whose status is fixed by their natural position within the hierarchy of beings. Apuleiusâs De deo Socratis remained long influential in Christian tradition, despite its incongruence with the notion of demons as fallen angels; for Apuleius, daemones were rational beings whose natural sphere was the sublunary air, just as gods and humans are rational beings residing in the ether and on earth respectively. They are not naturally evil, but may be either good or evil.3 The conjurations of late medieval necromancers, resembling as they do the exorcisms intended for the possessed, presuppose that the spirits in question are the same sort of fallen ones that Christ expelled from the energumens of first-century Palestine. But intermingled with references to such manifestly maleficent beings are notions of benign or neutral spirits, neither angels nor demons in classical Christian terms, a category not recognized in the orthodox theology of the late Middle Ages.4 One might thus say that the conjurations betray a tension between âdemonologyâ and what we might call âdaimonologyâ.

Theologians as well as necromancers believed that the demons held various ranks, in a kind of hierarchy that parodied that of Godâs heavenly court, or rather a âLowerarchyâ, as C.

Download

Forbidden Rites: A Necromancerâs Manual of the Fifteenth Century (Magic in History) by Richard Kieckhefer.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

What's Done in Darkness by Kayla Perrin(25500)

Shot Through the Heart: DI Grace Fisher 2 by Isabelle Grey(18220)

Shot Through the Heart by Mercy Celeste(18160)

The Fifty Shades Trilogy & Grey by E L James(17776)

The 3rd Cycle of the Betrayed Series Collection: Extremely Controversial Historical Thrillers (Betrayed Series Boxed set) by McCray Carolyn(13189)

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck by Mark Manson(12912)

Scorched Earth by Nick Kyme(11833)

Stepbrother Stories 2 - 21 Taboo Story Collection (Brother Sister Stepbrother Stepsister Taboo Pseudo Incest Family Virgin Creampie Pregnant Forced Pregnancy Breeding) by Roxi Harding(11040)

Drei Generationen auf dem Jakobsweg by Stein Pia(10217)

Suna by Ziefle Pia(10186)

Scythe by Neal Shusterman(9263)

International Relations from the Global South; Worlds of Difference; First Edition by Arlene B. Tickner & Karen Smith(8608)

Successful Proposal Strategies for Small Businesses: Using Knowledge Management ot Win Govenment, Private Sector, and International Contracts 3rd Edition by Robert Frey(8419)

This is Going to Hurt by Adam Kay(7695)

Dirty Filthy Fix: A Fixed Trilogy Novella by Laurelin Paige(6453)

He Loves Me...KNOT by RC Boldt(5805)

How to Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired by Dany LaFerrière(5378)

Interdimensional Brothel by F4U(5304)

Thankful For Her by Alexa Riley(5162)