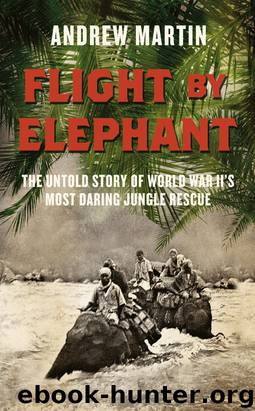

Flight by Elephant

Author:Andrew Martin

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollinsPublishers

Published: 2013-04-23T16:00:00+00:00

But this was different.

A full hour after first hearing the roar of the Dapha through the trees, the Mackrell party was still cutting through steeply descending jungle. At the foot of the incline, they arrived at the top of a cliff. In the gorge below was the Dapha. The cliffs bordering the river varied from sheer drops of 250 feet to 50-foot slopes. They found one of the latter, and took the elephants down. The margins of the river within the gorge were ambiguous: there were low plateaux or marshy tracts on which grew lemon trees and ten-foot-high grasses, and there were strips of rocky beach. This ambiguity made the river additionally dangerous. You’d think you were beyond the edge of it, then with a sudden surge it would reach out and pull you in.

Here the wild elephant track they had been following veered away from the water – which was very sensible of the wild elephants. Mackrell, his men and their own elephants stood next to the sagging shelter in which Millar and Leyden had spent the night after their own crossing and they contemplated the river. They did so in silence, because its noise made speech inaudible. They stood in a vast, right-angled valley. The Dapha thundered madly south, where it crashed into the Noa Dehing, immediately and crazily – like one drunk meeting another on a wild Saturday night – falling in with its plan of thundering west. The two rivers met in a great steaming cauldron hundreds of yards wide. As with Millar and Leyden, Mackrell sensed that he was intruding upon the private trauma of Mother Nature, and he would write in awed terms, ‘Few if any had ever seen the Dapha in the Monsoon before.’

Mighty tree trunks were bobbing around in the water, looking about as significant as human hairs being whirled down a plughole. These logs were ‘a terror to the elephants’, and some would not approach the river even after Mackrell and the mahouts had cut a pathway through the scrub to the water’s edge. Mackrell climbed up behind his personal mahout, Gohain, on the big tusker called Phuldot – the one that had taken the lead crossing the Noa Dehing at Miao – and they walked the elephant to the river’s edge. From here, ten feet up, Mackrell had a better view, and he saw amid the rainy mist a small grass-covered island in the middle of the river.

There were men on it.

None of them was Sir John Rowland, who at that moment was marching through the rain about 120 miles to the west These were small men, in ragged remnants of army uniforms, some wearing wide-brimmed felt hats: Gurkhas – sixty-eight of them. Mackrell did not know this, but they were the bulk of the party that had stayed a single night at Sir John’s camp, having arrived in the wake of those escapees from Japanese capture, Fraser and Pratt.

It was unusual for Gurkhas to need rescuing. As a rule, they were the ones doing the rescuing.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton(40330)

Introduction to Aircraft Design (Cambridge Aerospace Series) by John P. Fielding(32338)

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32141)

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(17445)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(7038)

The Complete Stick Figure Physics Tutorials by Allen Sarah(6638)

Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review by Kaplan(6053)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(5785)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5768)

Learning SQL by Alan Beaulieu(5411)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5036)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(4735)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(4702)

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport;(4540)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(4507)

Audition by Ryu Murakami(4098)

1,001 ASVAB Practice Questions For Dummies by Powers Rod(4038)

Electronic Devices & Circuits by Jacob Millman & Christos C. Halkias(4027)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4001)