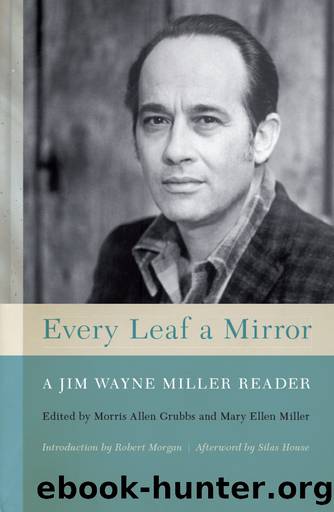

Every Leaf a Mirror by Morris Allen Grubbs

Author:Morris Allen Grubbs

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University Press of Kentucky

Living into the Land

The following essay first appeared in 1989 in Hemlocks and Balsams, the Lees-McRae College literary magazine. It is among Millerâs more than 150 essays, editorials, chapters, and the like. As Joyce Dyer, who has compiled a helpful bibliography of his nonfiction, has noted in ââAccepting Things Nearâ: Bibliography of Non-fiction by Jim Wayne Miller,â âMillerâs deep commitment to serving his region takes the form not only of frequent cultural commentary, but also of specific tributes to the men and women who made a deep and lasting contribution to Appalachian life and lettersâ (Appalachian Journal 30.1 [Fall 2002]: 64â73).

H. L. Mencken was fond of saying that our task as writers is not so much to discover new truths as it is to correct old errors. The notion that all literature is local somewhere, and that therefore the universal not only can be found in the regional, but must be found there, if anywhere, is not a new truth. Imaginative writing of all genres deals with particulars. The poet, Shakespeare says in A Midsummer Nightâs Dream, âgives to airy nothing/A local habitation and a name,â which is to say the poetâs abstractions reside in particulars. All effective writers of poetry and fiction choose âa bright particular star,â as Shakespeare puts it in Allâs Well That Ends Well. Neither art nor science, William Blake insists in Jerusalem, can exist âbut in minutely organized Particulars.â Traditional âuniversal-worship,â William James concludes in Psychology, âcan only be called a bit of perverse sentimentalism, a philosophic âidol of the cave.ââ Oliver Wendell Holmes writes: âYou must see the infinite, i.e., the universal, in your particular, or it is only gossip.â Flannery OâConner understood this philosophical error of âuniversal-worship,â and she knew, as George Ella Lyon points out, that âthe best American fiction has always been regional.â

Why then must we, where the reception and evaluation of literature is concerned, be forever correcting this old error, as if it were the stone of Sisyphus? There are many reasons. In the twentieth century, the success of the natural sciences, and their prevalence in our lives, surely has enhanced the reputation of the scientific method, which is to subsume many particulars under a general order. We are impressed not by the particulars but by the general order. J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of laboratory at Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the first atom bomb was built, writes, in The Open Mind, that the success of the sciences has made us âa little obtuse to the role of the contingent and particular in life.â

The literary modernism which has dominated critical perspectives in America in the twentieth century is biased against identification with place and hence against particular regions. Literary modernists such as Pound, Eliot, and Joyce, according to the critic George Steiner in Extraterritorial, are examples of a âstrategy of permanent exile,â writers who share a condition of âunhousednessâ and âextraterritorialityâ which has characterized the most influential writers and writing in our time.

The essential extraterritorial nature of the American national

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31332)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30934)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30889)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6472)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4868)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(4574)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4213)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(3582)

I Have Something to Say: Mastering the Art of Public Speaking in an Age of Disconnection by John Bowe(3516)

Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade by Robert Cialdini(3413)

Elements of Style 2017 by Richard De A'Morelli(2944)

The Book of Human Emotions by Tiffany Watt Smith(2770)

Good Humor, Bad Taste: A Sociology of the Joke by Kuipers Giselinde(2557)

Name Book, The: Over 10,000 Names--Their Meanings, Origins, and Spiritual Significance by Astoria Dorothy(2490)

Fluent Forever: How to Learn Any Language Fast and Never Forget It by Gabriel Wyner(2445)

The Grammaring Guide to English Grammar with Exercises by Péter Simon(2393)

Why I Write by George Orwell(2359)

The Art Of Deception by Kevin Mitnick(2297)

Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes by Daniel L. Everett(2216)