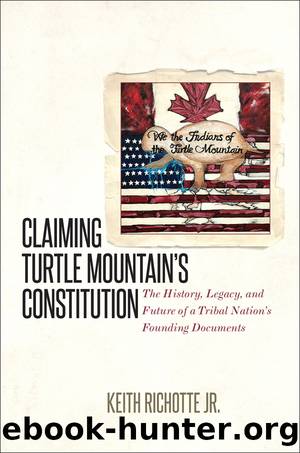

Claiming Turtle Mountain's Constitution by Keith Richotte Jr

Author:Keith Richotte Jr.

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Conclusion

By any rational measure, the constitution adopted by the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians in October of 1932 was a failure. It did not lead to the much desired claim against the federal government, it was not a particularly effective governing document, nor did it engender a sense of respect or validity within the community. It was immediately despised by many, and less than thirty years after it was adopted it was replaced. It left little in the way of anything practical or useful to structure or guide the government of the Turtle Mountain Band into the future. What it did leave, however, was a legacy to which the community continues to respond and that continues to shape constitutionalism at Turtle Mountain today.

A new era of federal policy created the impetus for change. The Indian Reorganization Act and its progeny had promised a rebirth for tribal nations, cultures, and lifewaysâto mixed resultsâthrough constitutions, corporations, and other investments in tribal life. A generation later the federal government took a vastly different tackâTermination. This new Termination Era was akin to one of its predecessorsâthe Allotment Eraâin that the government sought to âemancipateâ tribal peoples by severing the political relationship between the United States and tribal nations. Two significant developments during the Termination Era led to the demise of the 1932 Turtle Mountain constitution.

The first development to affect Turtle Mountain constitutionalism was the establishment of the Indian Claims Commission (ICC) in 1946.1 Created by Congress to manage the myriad claims sought by tribal nations, including Turtle Mountain, the ICC obviated the need to obtain a special jurisdictional act from Congress before engaging in a lawsuit against the United States. Instead, tribal nations filed claims directly with the ICC. For federal policy makers the ICC was a useful bridge between the IRA and Termination Eras and yet another in a long line of ideas that was appealing because it appeared to benefit everyone involved: the many tribal nations that sought to make claims against the United States would be able to do so, and the United States would be able to settle old debts and grievances before leaving the âIndian business.â2

Although more beneficial than most initiatives, the ICC was like so many other federal Indian policies in that it functioned better in theory than in practice. For most of its life, the ICC was undermanned, underfunded, and not equipped to manage the approximately six hundred claims that were eventually filed.3 Progress was exceedingly slow. Slated to last only five years, the ICC lived for thirty-two years and still had not finished its charge; the remaining pending casesâincluding Turtle Mountainâsâwere transferred to the Court of Claims.4 Originally conceived to cover a broad range of claims in a nonadversarial setting, the ICC quickly devolved into courtlike proceedings that narrowed the scope of the commission to land claims for monetary awards.5 Intending to finally make things right, the ICC may have created as many ill feelings as it resolved.6

Turtle Mountain filed its claim with the ICC in May of 1951, citing deficiencies with the Ten-Cent Treaty and its negotiations.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1685)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1618)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1542)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1444)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1406)

Tip Top by Bill James(1402)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1361)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1344)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1338)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1322)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1305)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1291)

F*cking History by The Captain(1288)

American Dreams by Unknown(1277)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1251)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1247)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1204)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1165)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1112)