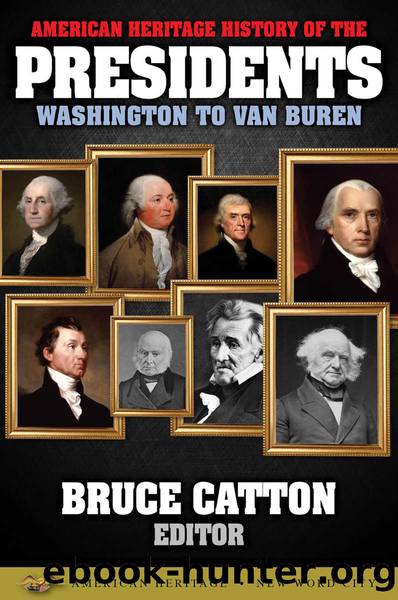

American Heritage History of the Presidents Washington to Van Buren by Catton Bruce

Author:Catton, Bruce

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Biography and Memoirs/Presidents and Heads of State

ISBN: 9781612309415

Publisher: New Word City, Inc.

Published: 2016-02-01T16:00:00+00:00

In May 1817, two-and-a-half months after he had become president, James Monroe left Washington for a tour of the Northern United States. Intending to inspect all the shipyards, forts, and frontier outposts for which Congress had voted large appropriations, he was also hopeful that his appearance would solidify national unity. Almost at once, he discovered that the trip was succeeding beyond his hopes: Roadsides and riverbanks were spotted with people anxious to have a glimpse of him, and cheering crowds greeted his arrival at state capitals. “In principal towns,” he wrote to Thomas Jefferson, “the whole population has been in motion, and in a manner to produce the greatest degree of excitement possible.”

After enjoying the receptions of the Middle Atlantic states, Monroe, perhaps bracing himself, entered New England, the last stronghold of federalism; the third consecutive Democratic-Republican president, he had lost Connecticut and Massachusetts in the election of 1816. But Monroe’s doubts about the enthusiasm of the Yankees were soon dissipated. On July 12, 1817, the Boston Columbian Centinel noted Monroe’s visit in this paragraph: “ERA OF GOOD FEELINGS . . . During the late Presidential Jubilee many persons have met at festive boards, in pleasant converse, whom party politics had long severed. We recur with pleasure to all the circumstances which attended the demonstration of good feelings.”

Whether or not feelings were really good during the “Era of Good Feelings” is a matter of conjecture, but the label became fastened to the Monroe administration, and the president profited. His popularity extended from the masses to many old political adversaries - the Columbian Centinel, for example, which was a dogmatic, consistently Federalist newspaper and a traditional foe of the Democratic-Republicans. Once a devoted party man, Monroe found himself the personification of nonpartisan paternalism, credited with all the good but rarely blamed for the ills of his two terms. Even John Quincy Adams - who rather than say anything nice about anybody could usually be counted on to say nothing at all - wrote that the Monroe years would “be looked back to as the golden age of this republic.”

The times were just right for James Monroe to assume the presidency. In his inaugural address, he said, “The United States have flourished beyond example. Their citizens individually have been happy and the nation prosperous. . . . The sentiment in the mind of every citizen is national strength. It ought therefore to be cherished.” Americans agreed: The success of their Revolution, of their experiment with republicanism, of their military engagements - most recently the War of 1812 - had buoyed their spirits and bolstered their national pride, unity, and ambition. Now the young country was growing, and a nationalistic generation, born under the American flag, was confident it could handle the problems expansion would raise. Still, Americans looked for leadership and example to the fathers of their independence. Washington was dead, Adams and Jefferson were old, and Madison was stepping down; but there was Monroe: If he had not forged the Revolution, he had at least helped to wage it, and, besides, he looked the part.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1693)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1620)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1546)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1452)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1419)

Tip Top by Bill James(1409)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1370)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1350)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1346)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1329)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1307)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1296)

F*cking History by The Captain(1289)

American Dreams by Unknown(1277)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1267)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1249)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1207)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1167)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1115)