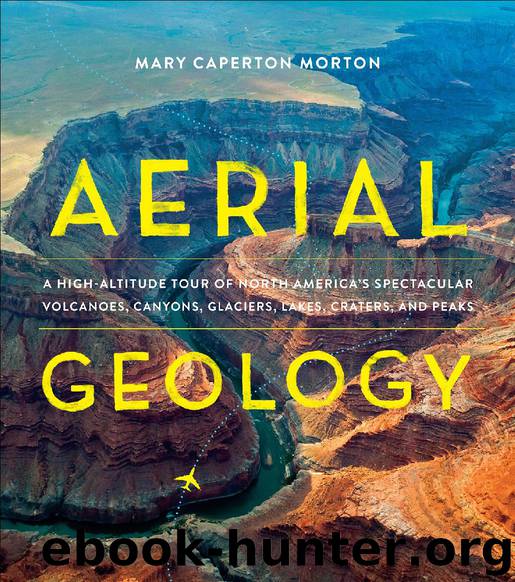

Aerial Geology by Mary Caperton Morton

Author:Mary Caperton Morton [Morton, Mary Caperton]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: gnv64

Publisher: Timber Press

Published: 2017-10-14T18:30:00+00:00

FLIGHT PATTERN

You might fly over the Rio Grande Rift en route to Santa Fe or Albuquerque, New Mexico.

VALLES CALDERA

New Mexico

Lining Frijoles Canyon are dozens of cavates and the remains of more traditional pueblo structures.

Remains of supervolcano eruption 1000 times larger than Mount Saint Helens

Supervolcano eruptions are infamously destructive—capable of smothering entire ecosystems under many feet of ash. But the eruption of the Valles Caldera supervolcano in what is now northern New Mexico actually created a unique habitat and way of life that sustained Ancestral Puebloans for hundreds of years. To see from altitude what is left of the volcano today, look for a circular depression in the Jemez Mountains just west of Los Alamos, and for white rocks blanketing the area to the north and east of the crater.

Valles Caldera is actually on the smaller side as far as supervolcanoes go, but the last eruption, around 1.25 million years ago, was still bigger than any eruption ever witnessed by man—over 1000 times bigger than the 1980 eruption of Mount Saint Helens. The rhyolitic magma produced by the Valles Caldera supervolcano was very high in water and other volatiles, making for a highly explosive eruption that spewed ash as far as Wyoming and Nebraska. The mixture of ash, pumice, and gases radiated outward from the caldera at speeds up to 200 miles per hour. At temperatures over 1700 degrees Fahrenheit, the pyroclastic flow would have incinerated anything in its path.

After the bulk of the volcanic material was ejected from the magma chamber, the floor of the caldera collapsed into the chamber below, creating a broad depression fourteen miles in diameter. A number of active hot springs, fumaroles, and gas seeps on the floor of the caldera are evidence of ongoing volcanic activity, as is Redondo Peak, an 11,253-foot resurgent lava dome inside the caldera, formed sometime after the main eruption and collapse.

The ash and pumice produced in the eruption created extensive pyroclastic deposits throughout northern New Mexico; these hardened into a rock called tuff. Just south and east of the caldera lies the Pajarito Plateau, cut through by Frijoles Canyon, once home to a unique settlement of Ancestral Puebloans between AD 1150 and 1600. Here, the tuff is relatively soft and residents of the canyon created cliff dwellings by hollowing out caves known as cavates in the walls of the canyon. They also built more traditional pueblo homes out of harder blocks of tuff and dug circular underground kivas for shelter from the desert heat. This complex of cavates, pueblos, and kivas is now preserved as Bandelier National Monument.

The people of Frijoles Canyon occupied their dwellings for hundreds of years before moving on to other areas of New Mexico after a prolonged drought. Glassy obsidian from the Valles Caldera has been found throughout the Southwest and Mexico, traded far and wide for use in making arrowheads, spears, and other sharp tools. Distinct isotopes in the obsidian make it possible to trace such tools back to their original source in the Jemez Mountains.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6001)

The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate by Kaplan Robert D(4066)

Zero Waste Home by Bea Johnson(3829)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3617)

Good by S. Walden(3545)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3535)

The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (The Princeton History of the Ancient World) by Kyle Harper(3055)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2855)

Camino Island by John Grisham(2793)

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotter(2684)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2678)

Human Dynamics Research in Smart and Connected Communities by Shih-Lung Shaw & Daniel Sui(2498)

Energy Myths and Realities by Vaclav Smil(2482)

The Traveler's Gift by Andy Andrews(2454)

9781803241661-PYTHON FOR ARCGIS PRO by Unknown(2365)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(2349)

Birds of New Guinea by Pratt Thane K.; Beehler Bruce M.; Anderton John C(2249)

A History of Warfare by John Keegan(2236)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2190)