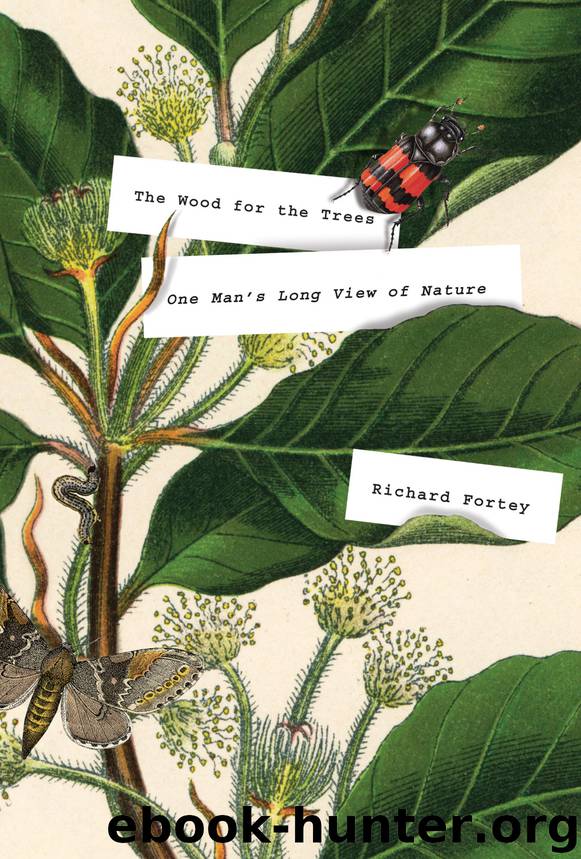

The Wood for the Trees by Richard Fortey

Author:Richard Fortey

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Published: 2016-12-06T05:00:00+00:00

Greys Court Affairs

The history of our wood and the story of Greys Court are intimately entwined. But even an estate like Rotherfield Greys cannot be fenced off from the outside world, as its game park might be from the privations of the peasantry. The early medieval period was one of increasing population and growth in trade. This accompanied a long phase of benign climate. If it had continued, woods marginal to the estate could well have been grubbed up and taken into arable use. The fourteenth century threw everything into reverse. The Great Famine of 1315–17 saw a succession of wet summers and implacable winters. Cereal crops failed. Seed corn was eaten in desperation. Starvation and the diseases encouraged by it took a huge toll; up to 20 per cent of the English population is thought to have perished. Cannibalism became a common crime. Global climatic change was caused by vast quantities of volcanic dust and gas released into the atmosphere by the catastrophic eruption of Mount Tarawera in New Zealand. Our wood was inexorably linked to events at the other end of the world. In the hard currency of tree girth this led to three years where little heartwood was added, just thin and measly growth rings that dendrochronologists use to recognise as a signature of those desperate years.

The Black Death followed in 1348–49, when bubonic plague swept through the land, respecting neither privilege nor estate. The historian Simon Townley estimates that Henley fared particularly badly because of its close connections with London—up to two-thirds of the population may have died. Afterwards, entrepreneurs moved back quickly, turning tragedy into opportunity. William Woodhall appears in the town records in 1350, was Town Warden two years later, and by his death in 1358 had a trading business stretching through south-east England. Henley kept its reputation as a commercial centre, and by the fifteenth century had enhanced it still further. From the narrow perspective of our wood, years of disaster meant that there was no pressure from population growth and so the forest was safe from clearance (assarting). It continued its useful life, its links with the past unbroken. But by now it should be clear that there were also links that connected our small piece of woodland in Oxfordshire with what was happening in the wider world. These links remain: they bind the whole biosphere together in common climatic cause. Viewed this way, the estate is global.

Generations of de Greys survived the difficult years, based at the manor house, which had by now lost any worthwhile function as a castle. The land was worked on through season after season, sustained by strict routines, but when labour became scarce after the ravages wrought by hunger and disease, statutes were passed to ensure that no advantage accrued to the workers. The interests of lords and merchants were, of course, protected. During a succession of minority heirs to Greys Court between 1399 and 1439, the old buildings became run-down. Later in the fifteenth century

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6001)

The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate by Kaplan Robert D(4066)

Zero Waste Home by Bea Johnson(3829)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3617)

Good by S. Walden(3545)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3535)

The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (The Princeton History of the Ancient World) by Kyle Harper(3055)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2855)

Camino Island by John Grisham(2793)

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotter(2684)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2678)

Human Dynamics Research in Smart and Connected Communities by Shih-Lung Shaw & Daniel Sui(2498)

Energy Myths and Realities by Vaclav Smil(2482)

The Traveler's Gift by Andy Andrews(2454)

9781803241661-PYTHON FOR ARCGIS PRO by Unknown(2365)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(2349)

Birds of New Guinea by Pratt Thane K.; Beehler Bruce M.; Anderton John C(2249)

A History of Warfare by John Keegan(2236)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2190)