Living the Revolution by Jennifer Guglielmo

Author:Jennifer Guglielmo [Guglielmo, Jennifer]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, 0807833568, The University of North Carolina Press, (¯`'•.¸//(*_*)\\¸.•'´¯)

ISBN: 9780807833568

Publisher: University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2010-05-03T00:00:00+00:00

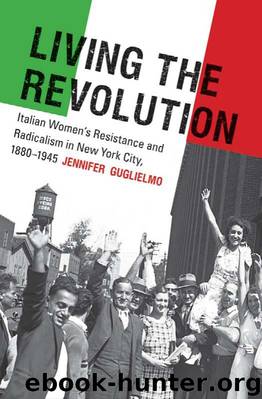

Antifascist rally on Fifth Avenue, New York City, ca. 1930. Banners include the Industrial

Workers of the World (iww), the Italian Antifascist Front, and several antifascist and radical

newspapers. Fort Velona Papers, Immigration History Research Center, University of

Minnesota.

came together to lead oppositional movements in their homes, neighborhoods,

workplaces, and unions. Most women entered the antifascist movement through

labor unions or family networks that connected them to the radical subcul-

ture. The Red Scare had crippled the organizational bases of Italian immigrant

working- class radicalism, but radicals reconsolidated in the movement to fi ght

fascism. Evidence of women’s participation in the antifascist movement exists

in photographs of rallies, often sponsored by the garment unions. It is also

revealed in the Italian- language press. During the summer of 1923, for example,

several Italian women snuck into a local fascist celebration and took to the fl oor

during speeches, shouting in Italian “Long Live Italy! Down with Mussolini!”

They also lunged at several of the speakers, causing fi ghts to break out and the

meeting to end.

Oral histories are also rich with evidence of women’s antifascist activities. Mar-

garet Di Maggio, who ran the organizational department of the Italian Dress-

makers’ Local of the ILGWU in the 1920s and 1930s, was also well known in her

222

D I A S P O R I C R E S I S T A N C E

Sicilian family for challenging those who “felt drawn by Mussolini’s promise of

grandeur to the Italian people.” Di Maggio’s niece recalled, “She and my grand-

father were always arguing. . . . She wanted to buy him a round trip ticket to go

back to Italy and see how things were.” When the arguments “got worse,” Marga-

ret bought him a one- way ticket and “within two months he wrote back here beg-

ging her to send him the return ticket.” Ginevra Spagnoletti joined an antifascist

group in her Greenwich Village neighborhood through her job as a buttonhole

maker. There she met organizers for the ACWA, and developed an interest in

broadening her social conscience. She joined the union and became fast friends

with Pietro Di Maddi, a socialist exile from fascist Italy. A regular contributor

to two left- wing antifascist newspapers, Il Nuovo Mondo and La Stampa Libera,

Di Maddi was a well- known fi gure in the antifascist movement. Ginevra’s son

remembered that Ginevra and Pietro were drawn to each other “by each other’s

intelligence and political leanings,” and they “struck up a friendship that devel-

oped into a close relationship.” Ginevra often hosted meetings in her home and

became more active in the day- to- day aff airs of the antifascist movement. While

her son remembered such meetings as a critical part of his own politicization, her

“outspokenness” antagonized her husband Joe, who “had no interest in politics

and felt threatened by his wife’s disposition to voice her opinions.” During one

heated argument Joe slapped Ginevra, telling her to “keep quiet like a woman

should.” Ginevra gathered her six children and left him for good that night.

Many women organizing in the garment trades at the time, including Lucia

Romualdi, Lillie Raitano, and Josephine Mirenda, became active in antifascist

circles and in the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

International Integration of the Brazilian Economy by Elias C. Grivoyannis(108356)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12012)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8038)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7689)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7101)

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert T. Kiyosaki(6598)

Pioneering Portfolio Management by David F. Swensen(6280)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6001)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5782)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4738)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4460)

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff(4273)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4232)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(4188)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4177)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3986)

The Dhandho Investor by Mohnish Pabrai(3754)

The Wisdom of Finance by Mihir Desai(3726)

Blockchain Basics by Daniel Drescher(3571)